Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

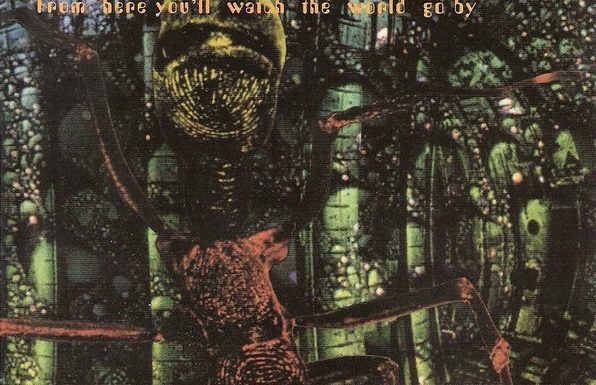

From Here You’ll Watch the World Go By (1995)

Tom: January 2021. Trump out, but Trumpism lingers. Anti-vaxx or anti-mask idiocy closely linked to that. A vociferous 20 per cent or so of the British public are seemingly wilfully lapping up everything Trump, QAnon, anti-mask, anti-vaccinations, as if it is an obligatory suite of views for the “free thinkers”. Britain does well at vaccination rates, as this programme was entrusted to the NHS. The EU makes some significant missteps responding to Covid following that 2016 to 2020 period where it basically out-manoeuvered Britain without any effort whatsoever, just by turning up and preparing. Lockdown #3 is a drag, it feels going against life not to be able to gather and meet beyond your household. Whatever the undoubted green benefits of less travel for the planet, this sort of total restriction feels life sapping. Hopefully, though, returning to activities such as going out to a restaurant, a pub, the cinema or a music gig will make me appreciate them all the more. Absence builds up expectation and longing. While the economic hit is to be taken very seriously, I haven’t seen any alternative to lockdown and approaches in Asia and Australasia seem, at least on current evidence, to be most effective in enabling a return to something more like normal. The useless idiots Toby Young, Allison Pearson and Julia Hartley-Brewer offer no plan for what happens if their laissez-faire herd immunity approach means the virus rips through the community even more and hospitals are overwhelmed.

Amid such a grim trial of endurance as this is, in the darkest, wettest, most monotonous January I can have experienced, it is great and instructive to turn once again to the venerable back catalogue of the Legendary Pink Dots.

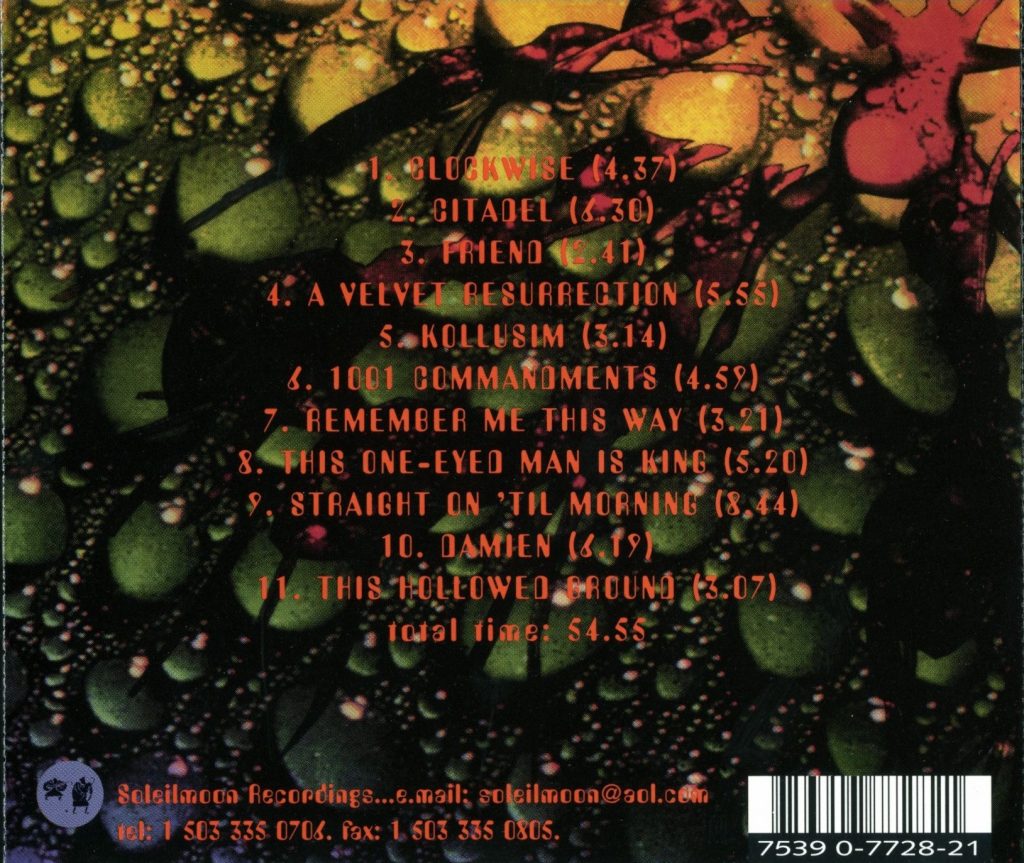

‘Clockwise’ opens, accessible, guitar led. The “Plimsoll line”, which Samuel Plimsoll indefatigably campaigned for, which limited the excess cargoes which often directly led to boats capsizing and sailors’ deaths. In his excellent 1950 book Roads to Ruin, which I finished reading over Christmas, E.S. Turner details how this seemingly modest reform was vigorously opposed by vested interests including MPs in their establishment lair of Parliament. The deceptively jaunty tune accompanies an ironic tale, possibly from a dead mariner in a surreal “heaven” with a “Brave Sir Henry” (Rawlinson?) swimming the Serpentine in 16 seconds flat. The final verse implies a rites of passage, leaving childhood behind.

‘Citadel’, the mythos of which we encountered before in Four Days (1990) is LPD in archetypal ominous melodrama mode. There is a carnival-esque upending of everyday idioms like “bless his little cotton socks!” and it ends “Come to Daddy!” a few years in advance of Aphex Twin. I think I’d have loved this if I’d heard it at the time. After all, I got into The Piper At the Gates of Dawn very easily. We hear the album title near the end a virtuoso tale of absurd horror. Descending one from the previous release, we get repetitions of “six”, apt given that I am just introducing Rachel to Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner (1967-68) for the first time!

‘Friend’ is a fine change of gear, with its waltz time, guitar and vocals minimalism. There is a chanson like simplicity to this, like Georges Brassens or Jacques Brel. Friendship juxtaposed with persecution. In the booklet to Asylum Relapse (2018), Patrick Q. Wright outlines the importance of discerning some essential binary differences around you:

“Being able to feel that difference seemed vitally important to me. Delusions of grandeur versus true Knowledge, Paranoia versus Sensitivity, Madness versus Wisdom, Brave Hero versus Mass Murderer… I prayed I’d always be able to feel that difference.”

Here, Ka-Spel seems to signify that his narrator has encountered duplicity and needs to be a better judge of what loyal friendship actually means. In the world of 2021, it seems just as important as checking our own privilege is the need to examine our own delusions of grandeur and paranoia.

‘A Velvet Resurrection’ is something else again. Languid acres of 1990s synth beckon us into a futuristic lagoon. This is great: EKS provides a grave, depressed rumination, wanting to believe that humanity is essentially good. God, morality, agency. The masks we wear. Can we stand alone and love one another and cherish life without the “spectre that died”, God. EKS is in the profound declarative mode, open and chastened. But, typically and wonderfully, he undercuts it with bathetic humour to close. Which is followed by an odd vocal sample of a man in a starchy RP accent saying: “bloody damn soyas (?) come back to Dalston”. The song ends enigmatically and dankly, its simple, furtive arpeggios fading to leave final ghosting synth tones.

The following ‘Kolusim’ escorts us, drifting, through a dank lagoon, serenely empty but with a distant beat emerging around the 100-second mark. An ambient interregnum; the simplified phonetic title reminds me of Russell Hoban’s novel set in a post-nuclear England Riddley Walker (1980) which I started reading recently. Then, ‘1001 Commandments’ hits us like a velveteen punch in the gullet. This is a barbed, cantankerous and unsteady highlight, a recognisably LPD venture into new inlets. The beat is thoroughly danceable, indeed even a disco beat! Ka-Spel’s singing is rhythmic, incantatory and intense. This grows and grows into incredible shapes, as Ka-Spel twists and mangles the phonemes he is singing into variants, like shards or sherds found in the ground to be repurposed.

‘Remember Me This Way’ opens, a resounding rock song ballast for the good ship HMS (or should that be LPD) From Here You’ll Watch the World Go By. There has been a cataclysmic change in the first-person protagonist. The music is richly accessible, but with occasional synth interjections and what sounds like a trilling, shrill telephone ringing! To close there is a fairly smooth saxophone and you get the sense this would be an accessible gateway into the LPD world for a newbie.

‘This One-Eyed Man is King’ is an unhinged melodrama, with something of the shamanistic mania Russell Hoban depicts in one of the titular Riddley Walker character’s ‘connexions’. This seems a woozy, unstable future world, though possibly more climate catastrophe rather than nuclear war: “it’s pushing 98 I’m walking through a desert that stretched halfway across the globe”.

‘Straight on Til Morning’ is staggering, for me one of three album summits to follow ‘A Velvet Resurrection’ and ‘1001 Commandments’. This is another LPD song to share its name with a Hammer film, here Peter Collinson-directed thriller Straight on Till Morning (1972). A crucial two-note descending guitar refrain pervades, accompanied by bright and ominous synth blasts and a cantering beat which suggests a new film genre of horse-movie to replace road-movie. “This road is mine now… And I’m out here and nothing matters.” An endless, “backwards” road, with reversing sound effects adding to the sense of existential dread and entropy. This is another of those EKS “spoken” epics, and, blimey, it needs every one of its 510 seconds. Used to people in the media banally saying: “now, we’re going on a journey”? Well, that hackneyed phrase is for once justified, here.

‘Damien’ is the LPD’s own distinctive take on The Omen (1976), but with added psychedelia and politics. Damien is deceptively ordinary and fuses nationalism with “red hot Bibles”, taking “the fear away with whitewash and scorched earth”. “You could feel the patriotic roar come pouring through the cracks of existence.” This has an uncanny resonance for me as 1995 was the year I had a right-wing nationalist phase, in reaction to not fitting in with the diffuse liberalism around me in my new comprehensive school. So, I well know the deep “imagined community” full of mystique of continuity that the likes of Benedict Anderson and Patrick Wright have analysed and that I now caution against.

Ka-Spel intimates this is the devil as a totalitarian dictator: “And the buses ran on time.” I recall this truism being repeated on several occasions when studying Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini’s regimes in GCSE and A Level history lessons. The makeshift rebellion against Damien is carried out in the name of “all the girls he [Damien] never had and all the boys who stood and laughed and all the dopes and all the dealers, the peelers, Sheilas, feelers, squealers”. There isn’t necessarily any sense that this is an actual, tangible revolt as the narrative ends cowering “in the corner of your room.”

‘This Hollowed Ground’ closes proceedings with a hopeful, guitar-led ballad of atheism and escaping clock-time. To me, this implies the dismal discipline of the 9-to-5 working day (which is admittedly vastly better when you have autonomy over your work, as is the case with my current PhD studies). This is the sort of Humanist anthem that the official Humanist organisations don’t even know about in their cocooned rationalism. Rebuilding a broken world with peace, love and inter-dependency? It is going to be needed. The aforementioned three peaks are among my very favourite LPD music so far and ‘This Hollowed Ground’ ends what feels like Imperial Phase LPD, a similarly clock-defying thing to the song’s sentiments.

Adam: The press release for FHYWtWGB suggests an album released amidst tumult, noting that 1995 had seen the band quit their record company, re-join their record company, start their own record company, organised a world tour, and gotten involved in numerous solo projects. Unlike the brilliant but scattered The Golden Age (1988) however, you would not get the impression that the album was recorded in anything but a mood of confident introspection, even tranquility. As Eric Watford from CMJ New Music Monthly reflected at the point of the album’s release, From Here is an “accessible album […] chock full of good tunes as well as adventurous wandering in complex textures and styles”. Watford notes that these styles are agreeably diverse and I would assent that the album is one of the Dots’ most balanced releases, offering one acoustic ballad for every two ambient-industrial dance tracks. It doesn’t quite have, however, the thematic coherence of The Tower (1984), The Maria Dimension (1991) or Shadow Weaver (1992), nor the intriguing excursions and deviances of Asylum (1985) or Any Day Now (1988). It is a resolutely solid, even workmanlike album with some seductive mood pieces and a couple of bangers, including the first track…

‘Clockwise’ begins the album on a lush and hopeful note, full of the promise of spring. If you caught it on the radio you might, at first, be forgiven for thinking you’d tuned into a late Manfred Mann single. Most of all, for me, it recalls the opening bars of Cat Stevens’ ‘But I Might Die Tonight’ used to yearning, disconcerting effect over the opening credits of Jerzy Skolimowski’s dreamy and disturbing 1970 cult classic Deep End, a film of youth interrupted and innocence lost. Similarly, in ‘Clockwise’ Edward reflects that “childhood ends and “sense” descends” as technological beeps and blips intrude upon this sunny pastoral. A reading of the song as uncomplicatedly peppy would suggest this represents a transcend unity of nature and technology as per the one envisioned in Richard Brautigan’s 1967 poem ‘All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace’:

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

However, as per usual with the Dots (and as per Adam Curtis’ 2011 documentary about the rise of technocracy that goes by the name of Brautigan’s poem) any romantic idyll is at best a temporary reprise – and at worst a deluded distraction – from the maniacal machinations of power and politics.

These come marching into view with the second track ‘Citadel’, the sound of steps providing a counterbeat to the drums. Then enters what sounds suspiciously like the noise of a ruler vibrating at the edge of a table (which I insist was used to create the distinctive eerie noise in Bauhaus’ ‘Bela Legosi’s Dead’) though is probably barre chords played with open strings or somesuch! Musically it is a seductive slinky song of enjoyable menace. Lyrically it’s Theseus in the Labyrinth re-envisioned as corporate horror. I picture it as a cross between Václav Svankmajer’s short film Torchbearer (2005) and Baroque Decay’s 2019 survival horror game Yuppie Psycho. In imagining this combination I think I have finally managed to make a Googlewhack of references that only I will get! The track, like ‘Neon Gladiators’ from all the way back on 1984’s Faces in the Fire, takes the listener on a clandestine journey, but here I find the effect oddly distancing, like a friend relating a D&D campaign you weren’t part of.

Track three, ‘Friend’, is a piece of gothic whimsy like ‘Princess Coldheart’ from Crushed Velvet Apocalypse (1990). More like Lloyd the ghost bartender in The Shining (1980) than Drop Dead Fred (1991), the imaginary friend of the song’s title whispers insinuating secrets and allows the singer to “rip [the] metal mask” from off his face and hold his head up high amongst the beautiful people. Like the childhood revelry of ‘Clockwise’, however, it doesn’t last and soon the narrator falls back into loneliness and isolation. Musically the track is a curious ditty, like one of the Decemberists’ faux-sea shanties. It has more of a bridge back into the verse than a chorus proper. Rather slight at only 2:44.

‘A Velvet Resurrection’ is the one track on the album that sounds singularly of the time it was released. It’s one of those spoken word ‘90s indie-dance tracks like Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen)’, Eels’ ‘Susan’s House’, or Boom Bip’s ‘The Unthinkable’ (technically 2002), but it’s better than any of them! Against celestial washes of ambient drone, Ka-Spel intones his desire to believe in human goodness and the forward march of progress from superstitious persecutions (“that haunted our fragile globe for just too long”) to an enlightened humanism. This mirrors the liberal philosophic idealism of Václav Havel, one of the visionaries who helped to spark the Czech Velvet Revolution that the track’s title references. Of course, when in power, Havel’s liberal idealism curdled into the nationalist neoliberalism of his successor Václav Klaus. I actually used the track in an online service for the Ipswich Unitarians on embracing ambiguity and not-knowing-ness. Ka-Spel often seems to take Samuel Beckett’s famous adage from the end of The Unnamble (1954) spiritual orientation of “I can’t go on, I must go on” and transform it into the more collectively encompassing “We can’t go on, we must go on”, though here he is stuck within personal pessimism, just as he yearns to move beyond it. What Tom takes to be “bloody damn soyas come back to Dalston” is, apparently, “[Be] bloody damn sure you come back as a dolphin”, recalling Ka-Spel’s sentiment in ‘Evolution’ on The Maria Dimension and Douglas Adams:

“Man has always assumed that he is more intelligent than dolphins because he has achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on —while all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But, conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.”

‘Kollusim’ is a bit of a sedate stopgap after the brilliance of ‘A Velvet Resurrection’, like a track from Apparition (1982) played underwater.

‘1001 Commandments’ is a masochist’s groove like ‘True Love’ from Any Day Now or a good half the tracks on Crushed Velvet Apocalypse. Some of the promises like “I’ll never shout you down, I’ll never shut you in, I’ll never lock you out…” sound perfectly reasonable; but then we get on to “You’re upstairs with him and when he goes away and you cry out your pain, but here I am again […] I’m on my hands and knees and you can cling to me and pin some wings on me and I will ride the breeze, I’m only here to please” and all I can picture is Lawrence of Arabia being flagellated in the desert.

‘Remember Me This Way’ completely washed over me listening to it on my crummy laptop speaker, but revealed its richness when listened to on a decent pair of headphones. Its a bit of a wall of sound production with splashy cymbals and guitar reverb. It chunters along like a solid rock standard with lyrics about a former lover who wouldn’t want to see the narrator now that the years have taken their toll. The track fades out and into the swampy soundscape of ‘The One-Eyed Man is King’. It’s another headphones track which wouldn’t sound out of place on The Maria Dimension. The scenario described recalls the terrifying hothouse earth predictions made in David Wallace-Wells’ 2017 New York Magazine article ‘The Uninhabitable Earth’, later extended into a 2019 book of the same name. On page 39 of that book Wallace-Wells writes:

“Humans, like all mammals, are heat engines; surviving means having to continually cool off, as panting dogs do. For that, the temperature needs to be low enough for the air to act as a kind of refrigerant, drawing heat off the skin so the engine can keep pumping. At seven degrees of warming, that would become impossible for portions of the planet’s equatorial band, and especially the tropics, where humidity adds to the problem. And the effect would be fast: after a few hours, a human body would be cooked to death from both inside and out. At eleven or twelve degrees Celsius of warming, more than half the world’s population, as distributed today, would die of direct heat.”

Ka-Spel’s narrator calls the spirits of the trees, “It’s pushing 98 degrees” and like Lauren Oya Olamina in Octavia Butler’s ‘Earthseed’ books, walks across the desert “sucking stones” to stave off hunger. The same narrator’s abortive ‘Hero’s Journey’ seems to continue on the following track ‘Straight on ‘Till Morning’. The music here is wetter; heady. It is oddly similar to the music used in Ice-Pick Lodge’s brilliant existential survival horror games Pathologic (2004) and The Void (2008). The lyrics describe the narrator suspended in a purgatorial journey, trudging ever forwards only to discover he has been walking backwards the whole time and is unable to turn around. Again, Samuel Beckett comes to mind, but this time the mud-bound narrator of How It Is (1961/1964) with his lost sense of narrative and spatio-temporal progress.

‘Damien’ is a lush track reminiscent of Pink Floyd. While my allegiance tends to be with the weirder contingent of the Dots’ output, this straight-up cosmic rocker is my favourite track on the album. The guitar is allowed to roam wild and free Gilmore-like and van Hoorn’s horns squeal and scream something terrible. The lyrics sound to my contemporary ears as being about an incel/Gamergater turned messianic dictator. For me, the best take on this toxically masculine mindset from the perspective of a mass shooter is by the Sparks/Franz Ferdinand super group FFS and their chilling track ‘Little Guy from the Suburbs’. I must admit to wanting Matt to renew Kitty Sneezes’ dormant Sparks Project so he/we can cover this one! The one misgiving I have about ‘Damien’ is that the song doesn’t whatsoever raise the spectre of The Omen for me outside of the reference of the title! While I am only a lukewarm fan of the film, I have a soft spot for the unofficial video game adaptation Lucius (2012) – and in particular its 2016 demake – where you play the wee little spawn of Satan himself.

Finally, the final track of the album proper, ‘This Hollowed Ground’ is a lovely piece of work of immense gentleness. It was the other track I used in my Unitarian service since it pictures a world beyond the ossifying symbols of a life-denying Christianity that severs humans from the cyclical, variegated rhythms of nature in favour of utilitarian clock time, thus returning us to the themes of the album’s opening track, ‘Clockwise’. This is quite a major concern of my book (*ahem* self-promotional plug) The Art of Czech Animation (2020), which draws upon my experiences in Extinction Rebellion. Perhaps the most potent Czech stop-motion film to embrace the same paganistic themes of Ka-Spel’s poetry here is Jiří Barta’s wonderful Balada o zeleném dřevu/A Ballad About Green Wood (1983). In this film, splits of wood dance wildly in a spinning circle to celebrate the coming of Spring, until all of this is interrupted by a man wielding an axe with a digital watch upon his arm. For me personally the track is the most beautiful and restorative piece of music released by the Dots since ‘We Bring the Day’ from Malachai (1993), which not coincidentally covers the same themes.

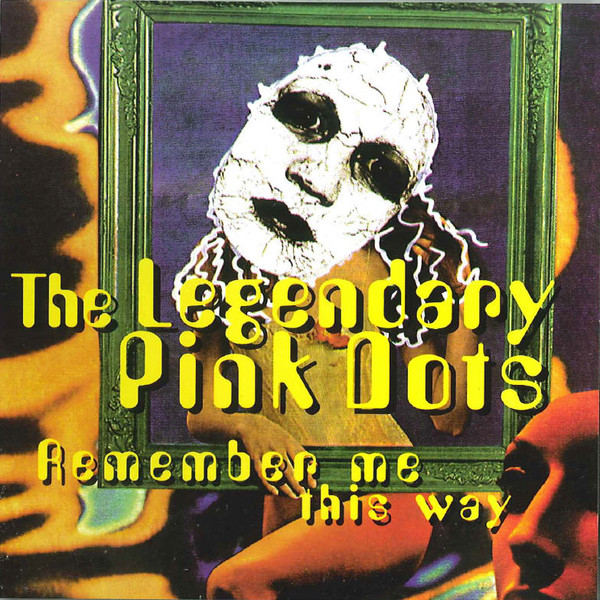

So… that’s the FHWWtWGB LP, but now we jump forward in Tom’s writing three months to April 2021 (sorry Tom!) to cover the worthy remnants collected in the Remember Me This Way EP from 1996.

Tom: ‘Beautiful Machine’ is a cartwheeling emporium, giddily constructed, its shelves adorned with shiny products betokening change. Ka-Spel hymns the machine in terms akin to techno-utopianism, or is there an undertow of irony? We are immersed in perhaps the thousand and first plateau of Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Ecology and the machine; or, rather the rhizome and the desiring machine, as clearly elucidated in Matthew Sweet’s excellent BBC Radio 3 programme on this French thinker and doer duo.

The two rising, insurgent ideologies in the 1990s very much continuing from the previous decade, but diverging where they had seemed to be coalescing in 1988, as Nathaniel Rich outlines in his excellent book, Losing Earth: The Decade We Could Have Stopped Climate Change (2018). The first is environmentalism. The second is techno-utopian libertarian capitalism, which some have even termed ‘anarcho-capitalism’, combining the mercantile tradition with the posturings of piracy which links to rave music ‘entrepreneurs’ (Paul Staines) or rogue traders in derivatives (Nick Leeson). Oddly enough, these two ‘gentlemen’ were born in the same month – February 1967 – and in Ealing and Watford, both part of South East England. ‘Beautiful Machine’ seems to affirm the binaries between technology/nature and capitalism/environmentalism, but is surprisingly shy about communicating any direct opinions.

‘Anastasia’ is also comparatively major-key; though the lyrics concern Faustian pacts, private armies and idealising America. The latter seems ever more telling in our time when centrists in British media and politics are religiously checking county-level US presidential election data, while not knowing or caring much about European countries’ politics or even about long-term austerity across British towns and cities.

This resolves into a scarily accurate foreshadowing of 9/11 and Bin Laden. We have just finished watching Granada’s psychological crime drama series Cracker (ITV, 1993-2006). Its final episode, when it returned after ten years is, while ropey in its main plot, intensely topical with hard-hitting, well-judged references to the property boom and the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars. Jimmy McGovern, even more bluntly than certain Russell T. Davies Doctor Who stories, makes it seem like TV dramatists were the main opposition to the government, Robin Cook having died in August 2005 and Charles Kennedy being replaced as Lib Dem leader in January 2006.

The “War on Terror” represents a Manicheanism all the more damaging in how it precisely mirrors the inhuman intensity of the other side: adopting the subject position the ‘enemy’ desires. To paraphrase a saying the actor who plays DCI Wise in Cracker is well known for elsewhere: rehabilitation of George W. Bush my arse! Of course, Ricky Tomlinson, along with all other members of the Shrewsbury 24, have been cleared themselves in the past month of offences they were convicted for in 1973-74 of ‘unlawful assembly’, ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ and ‘affray for picketing’ when they had been striking for better wages and health and safety in 1972 when many builders were injured or killed on building sites.

In ‘Day Zero’, pale psychedelia becomes nightmarish militarism, with marching rhythm. Generals’ heads on balustrades and mile high rises. The title suggests Pol Pot and the genocidal Cambodian “Year Zero“, another murderous iteration of communism. The screening of John Pilger’s ATV documentary, Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia (ITV, 30/10/1979) may have been one of several events that turned the tide in the general culture even further against authoritarian communism. It just a shame that it wasn’t humanist socialism that came to dominate the “marketplace of ideas”. Pilger’s film also highlights how Kissinger and Nixon enabled and acted as a catalyst for the Khmer Rouge and how Western embargoes were counterproductive; such mistakes keep on being repeated with regard to extremist Islamism.

The generals are hanged with flags, which bears 2021 relevance, as apparently TV presenters are not allowing light hearted jokes about the British Union flag and politicians compete absurdly to include flags in their homes for Zoom appearances. That this is being normalised shows that any more gentle and dignified expressions of patriotism are being supplanted by boastful ostentation – an impression bolstered by the petrified overkill of the BBC’s coverage of Prince Philip’s death last week.

Adam: The full length version of ‘Remember Me This Way’ gives the band more space to cut loose, turning it into more of a psychedelic jam. ‘Beautiful Machine’ is a crunky steam-powered patchwork of a daffy ditty… a little like the Bonzos and a little Residential. Apparently the repeated final line is “Evening’s just a snip away” but I prefer to hear “Who needs justice anyway?” There’s more malarky with ‘Anastacia’, this time bossa nova tinged with two-tone organ. It’s pleasingly nutty and would have been completely out of place on the album – unlike ‘Day Zero’, which would have slotted it just fine. I holds a slinky but militaristic zithery intrigue. Sonically it is a little cramped… my partner called it fruity.

The Bandcamp has alternative versions of ‘Damien’, ‘A Velvet Resurrection’ and ‘Friend’… the tracks (especially the first two) are as essential as ever, but not terribly different to the originals!