Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

—

Tom: That rarity now as we skip a year in our grand survey: there were no LPD albums released in 1987, at all. 1988 saw some great music – Pet Shop Boys’ Actually, A.R. Kane’s 69, Inner City’s ‘Good Life’, Prefab Sprout’s ‘Cars and Girls’ and S’Express’ ‘Theme from S’Express’, for starters. This was a radical time for the UK charts: in 1987 M/A/R/R/S had a #1, ‘Pump up the Volume’, a double A-side with the even better ‘Anitina (The First Time I See She Dance)’. 1988 also saw the Indian Summer of Thatcherism in the UK, with Thatcher herself seeming impregnable and her legacy being cemented. A MORI poll in late January 1988 saw the Tories on 50%, fourteen points ahead of Neil Kinnock’s Labour. Kinnock had been allowed to stay on followed a ‘creditable’ landslide defeat in the June 1987, and was leading the opposition in a steadily rightwards direction. By the end of the year, Kinnock had easily seen off a challenge from veteran socialist MP Tony Benn, but was still ten points adrift of the Tories in MORI’s last poll of 1988. Geopolitically, the world was getting safer, but few were taking anything for granted: the Soviets were still in Afghanistan. So, what about the Legendary Pink Dots’ 1987-recorded seventeenth album? The title is recursive: referring back to a phrase from The Tower (1984).

The opener ‘Casting the Runes’ has echoes of M.R. James, with a grid-like synth pattern snaking into view. The inimitable violin of Patrick Q. Wright enters, followed by stealthy, loping bass. The mordant tale of Madeleine, who has eternal life, is told with pathetic fallacy (“it always rained”) and sampled hammers clanging on metal. She signifies bad omens and the violin, as often on this album, evokes Eastern Europe – linking it in my mind with The Lovers (1984). It’s a fine track to illustrate the Dots’ fusion of English and international influences.

We have great English Gothic lyrics like “Under twilight, we all walk around the stones […]

Hallucinations curtsey, as the river priestess consecrates the bones” leading directly into a rendition of the sterling chorus: “And that’s the way it will be, ‘til the end of time!” We hear these words aplenty: and so mote it be, to paraphrase the right Reverend Magister in the Pertwee-era Doctor Who serial ‘The Daemons’ (1971)…

The fine opener is followed by ‘A Strychnine Kiss’, which opens with Middle Eastern resonances rather like the opening to Transglobal Underground’s magisterial ‘I Voyager’ (1993). This song alludes, potentially, to the Catholic Church’s collaboration with the Nazis: “As the Pope licks a jackboot”. Some dissenting free jazz kicks back around 01:50. The song depicts the uneasy intertwining of capitalism and religion: “And the only survivors are him and his priests. In them thar seven hills there’s a big crock of gold, but it’s all stashed in sacks and belongs to a Pole. And name any language, he’s got something to sell, but if you add it up, it’s a ticket to hell.” Polish John Paul II had been Pope ten years by 1988. There’s also an allusion there to Mark Twain’s The American Claimant (1892), which depicts the Gold Rush; Colonel Mulberry Sellers has the catchphrase: “There’s gold in them thar hills”.

‘Laguna Beach’: is it Florida? Is it Atlantis? Wherever, it is a beautiful song. A delicate, plaintive piece built upon shivering bass depths and plangent, tinpot keyboard notes like stranded lighthouses – rather akin to the Emmerdale Farm or Brookside themes of yore. There’s an air of ineffable tragedy about it; that’s just out of reach: “Laguna Beach was soaked in tears, the sea retreated, the world retreated. Nothing left but sand…” The context is mysterious, there’s a deft, deliberate ellipsis of narrative and story.

“A castle rose, a story closed… too soon…”

Brought to mind is The Prisoner episode ‘The Girl Who Was Death’ (1967), wherein the ending pulls the rug from under our feet and gets us questioning stories and their purpose.

‘The Gallery’ is brilliant too; sedately uproarious like an impromptu tune in a Prague beer hall. It’s a strange, jaunty violin-led tale of a “building full of holes with heads in, staring at the street”. Ka-Spel offers choric backing vocals, with deepened effects: “(peeping)”, describing the beady eyes in the gallery. There are again hints of sportive jazz, though this is more Magritte than Matisse, in this zestful song delineating the absurdity of persistent spectatorship. I recently visited the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and an image of this song’s scenario would have fitted within its surrealism room, right alongside the likes of Max Ernst’s ‘Human Figure’ (1931) and Toyen’s ‘The Myth of Light’ (1946).

Next up is one of my favourite LPD tracks of any so far. ‘Neon Mariners’ is imperious all the way. Starting with gleefully clattering late-80s tribal synth-xylophone percussion (or whatever the hell it is!), Ka-Spel emerges with a particularly surreal, dream-logic lyric. “The cha cha bar was sliding”: ‘The Gallery’’s concern with public ritual continues, as there’s a strange, partial pub crawl across the sea. There are “so many rocks”, whispered closer to the mic by EKS. Following docking in Fish Head Harbour, they – shown by the indistinct first-person plural pronoun “we” – encounter another weird, uncanny bar. The lyrics are superlative:

“The floors was tin, the sky was oil, the air was poisoned lager and the juke box pumped out schlager because no-one pulled the plugs”

“Schlager” refers to the mainstream brand of 1960s German music, saccharine and sentimental, that musicians linked with Can, Kraftwerk, Faust, Neu! reacted strongly against with their own visionary music in the 1970s. A key account of this context is provided by David Stubbs, in his Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany (2014).

Then we are confronted – as that can be the only word – with the tremendous chorus: “Dance in brine. Dance in brine… Dance in seaweed…” Yes, you got that right: “brine”! This spectacularly surreal spectacle has been initiated by the “live wives”, “who kept us dancing”. Who are they? Whose husbands? Are they survivors?

Such questions have time to coalesce in the noggin while there’s an evocative, pause-for-breath interlude – dinky, music box chiming followed by stentorian Hammer horror organ, followed by further compact chiming. Then, back to the chorus. Frankly, it needs nowt else. Magnificent, munificent imperatives to “Dance in brine […] Dance in seaweed”, over and over and over again; backed now by organ, violin and synth forces conjoining in intense accord. The last rendition almost sounds like “drowned in seaweed”…

Next is another corker: ‘True Love’. This is a staggering slow-burner over its 201 seconds, which twists familiar romantic rhetoric into extraordinary shapes: “And if you asked I’d wear an iron mask. Oh! I’d chew glass for you. All for you . . . Pick a cloud, I’ll fly–I’d drink the ocean dry for you. If love is really blind, I’d pluck out both my eyes for you.” The hyperbolic declaratives become all the more extreme, with the narrator willing to go further even than the “vile jelly” eye-gouging of Gloucester in Shakespeare’s King Lear.

The chorus “all for you” disturbs and prods in its intensity, the main circling synth sequence is rather like Europe’s ‘The Final Countdown’ (1986) in Hell. It appeared in embryonic form in the earlier recordings captured on Any Day Now Secrets. For Any Day Now, it is embossed with violin flourishes, in comparison to the barer version ‘Thunderland + True Love Waits’. From 2:38, we have dynamic drum cascades heightening the tension. The narrator parenthetically reveals that his object of desire is in a bed, being pumped with morphine and screaming; this is following his claim that “still you say you love me”. The song starkly washes away, fades out to white, like an eye ceasing to have vision. The act of looking is clearly very important to this album; vision is often obscured by smoke.

‘The Peculiar Fun Fair’ is a necessary, effective fragment: 33 seconds of tinny computer game oompah music. A computer game made for bees. It buzzes out as briskly as it arrived, leaving us with radiophonic whirrs.

‘Waiting for the Cloud’. That mushroom one, for certs, as the lyrics indicate: “A mother force-fed baby milk which ticked and bubbled black. She sank it back with plastic pills although it stank . . . seemed thankful. Rolled up in her sack, she won’t be back, she won’t grow old . . . We saw it all in colour–now we’re waiting for the cloud.”

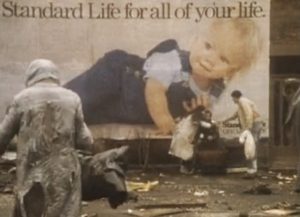

The image of the mother strongly evokes the BBC’s meticulously researched and utterly bleak nuclear-war drama Threads (1984), shown in pitiless colour and repeated to higher audience figures the following year. Glacial keyboard and mournful violin accompany lines like “She won’t grow old”, which darkly links back to ‘Poppy Day’. Things cease. Then, a second-section, opening massed strings and graffiti-like synth squiggles dissolving into… strangely Prog Rock-like grand synth organ chords. There’s a vaguely Mike Oldfield-esque guitar and the bombast of periodic timpani. This segues into a third section, with circling, jabbing, now Robert Fripp-like guitar. “Crocodiles grow wings”. The chorus again, “We saw it all in colour”. A baby cries, and we return abruptly to the first section and its dank, rich chord sequence. Ka-Spel shows how nuclear war doesn’t discriminate; it annihilates those the narrator is digging graves for:

“We’re told it could be 15 days, we’re busy digging holes . . . The deep ones for the pure, selected–shallow ones for old and sick, the derelicts, the poor, the junkies, criminals, the whores. There’s more, there’s red and yellow, black and blue. There’s me, there’s you.”

Historians paint it that nuclear fears were so rife in 1979-85 that we can easily neglect the fact that these attitudes and fears lingered beyond these years, even as Gorbachev and Reagan were seeing sense and doing deals. Writers coming through in the later 1980s and 1990s were often still steeped in this bleak outlook; for example, Doctor Who’s new, young script editor from 1987 Andrew Cartmel and the pool of writers he assembled. The hands-on Cartmel originally got the job partly due to his audacious claim that he wanted to overthrow the government and who often appeared on set with a t-shirt of the Roy Lichtenstein-style pop art piece, ‘NUCLEAR WAR?! …THERE GOES MY CAREER!‘ (1980). Indeed, Cartmel’s book Script Doctor reveals the irreverence and left-wing outlook of the regular and guest cast, with Sylvester McCoy carrying around copies of George

Bernard Shaw and criticising the media’s assistance of the Tory election win 1987, Catherine Cusack having a thing for Mikhail Gorbachev and Don Henderson with ever-present CND badge. The show, dismally creatively defunct in its late 1986 Trial of a Time Lord farrago of a Season 23, gradually picked itself up with stories influenced by JG Ballard, critical theory and, crucially, 2000AD comic. The show provided perhaps my first awareness of nuclear weapons: in 1989’s ‘Battlefield’, which I VHS recorded and re-watched endlessly with the rest of its Season 26. This is by far the weakest of its season, with some extraordinarily silly moments, but has a moment that shook me to the core as a seven year-old, watching. When faced with a medieval sorceress Morgaine (Jean Marsh) threatening to use nuclear weapons in mid-1997 England, seventh Doctor the Scot Sylvester McCoy, more of a diminutive underdog in comparison to the bullish Colin Baker as well as Jean Marsh, is given this speech:

All over the world, fools are poised, ready to let death fly. Machines of death, Morgaine, are screaming from above. A light: brighter than the sun. Not a war between armies, nor a war between nations… But just death, death gone mad! A child looks up to the sky, his eyes turn to cinders. No more tears, only ashes. Is this honour? Is this war? Are these the weapons you would use? TELL ME.

Viewed in 2017, it still seems a poignant powerhouse of righteous indignation; a little man with sadness and anger in his face and voice, calling human stupidity to account, once and for all. McCoy as the counter-cultural, CND Doctor? Yep, and one Ka-Spel would vouch for. From the vantage point of 2017, the sentiments expressed are of present-tense relevance, with the decline in multilateralism and ratcheting up of tensions, as Paul Mason explains: ‘All around us high politics is becoming emotion driven, unilateral, crowd-pleasing and falling under the control of erratic family groups and mafias, rather than technocrats representing ruling elites.’

The following ‘Cloud Zero’ is grave, sedate and slow, as you might expect, with its ripples of piano heralding the blank stillness, post-Armageddon. It is like a drugged, 78rpm take on the Bonzos-like sound of ‘Our Lady in Darkness’ from Island of Jewels (1986). The lyrics seem obscure, however, with the narrator speaking in second-person: “You’re watching the aeroplanes high in the sky and you cry.” From 2:20, the pace builds and a hovering violin enters. “You wish you could fly, but you’re far too high – and you’re going nowhere.” Perhaps it is the dream of someone post-Armageddon? Then, curiously again, it ends with plucked string notes and the tinkle of what sounds like a bicycle bell. This – to me, anyway – signifies the now-ness of Ka-Spel’s living in the Netherlands, emerging from the fug.

‘Under Glass’ I like less than everything else thus far. I can, in post-structuralist style, do a political reading – detecting the pun on ‘under-class’, tenuously noting the liberal feminist ‘glass ceiling’ concept and considering phrases like “To fortify your island” and “You throw your weight around” as presciently describing Theresa May’s idiotic, media-cheer-led “Hard” or even “Red, White and Blue Brexit” Britain.

The song does depict social class: a blue-collar worker “tough and loud”, but beneath the exterior, paranoid and weak. There’s more imagery of “holes”, following ‘A Strychnine Kiss’ with its cathedrals slashing holes in the air, ‘The Gallery’ with its voyeurs peeping through them and ‘Waiting for the Cloud’ with its dead being buried in them. But, overall, I just don’t warm to it; its chorus is humdrum and it really doesn’t need to be 427 seconds long!

‘The Light in My Little Girl’s Eyes’ begins with an ominous take on the consumer society. “Shops stacked high with stereos and rows of magazines. Smells of coffee, glossy limousines”. There is extravagant metaphor and surrealism: “The paving stones were playing cards”. It’s a typically elliptical scenario of transgression: “Watched ourselves in the mirror, like animals, like cannibals! And you ate my ear, so I nibbled on your shoulder”. Only the eyes are left, akin to The Cheshire Cat, and relating back to the peeping eyes from the heads in ‘The Gallery’. “It’s a Hollywood sunset! Hollywood. Hollywood. Holl-yyy-wood…” It is questioning of the usual images, and offers the bizarre instead. There’s self-referentiality in his final cry of “Brighter Now…”, as capering violin and astral guitar see us out.

And into the concluding, concise ‘The Plasma Twins’; somewhat post-punk guitar is interspersed with shrill keyboard notes. It is about merging, mingling; another grotesque LPD scenario, of having the other person’s blood pumped into yours: yet more of that verb phrase ‘to pump’. As well as a blood group-related pun, there’s an egalitarian aspect to this blood exchange: It’s nice to know we’re always sharing; a love like ours is rare.” There’s also further irreverent, playfulness with courtly rhetoric: “Give me plasma, be my plasma doll, my plasma lady fair…”

I don’t propose to write much about Any Day Now Secrets (2013) – will leave that to Adam – other than that it is a shame that ‘The Lounge’ wasn’t expanded and included. It is an evocatively yearning 72-second instrumental, with elegiac synth notes with ample sustain.

Any day now: an outbreak of world sanity? I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath as my namesake calls a self-interested election. Any Day Now? Song for song, one of the strongest releases yet… It is certainly not the cohesive beast that Island of Jewels is, but has enough political bite and more than enough good choruses to see us through!

Adam: In contrast to my usual experience with the Dots, it was the music rather than the lyrics which allowed me access to Any Day Now. Perhaps this was because previous album Island of Jewels was so immediately, intuitively graspable in post-Brexit Britain, providing me with the decidedly bitter-sweet comfort of finding the portrayal of a fascist dystopia relatable. By contrast Any Day Now casts its net far and wide and dredges back a water-logged patchwork of hessian and silk, threaded through with bits of glass and barnacles and the occasional plutonium rod. This eclecticism in theme and tone is accounted for by the material praxis of the album’s conception – that is to say, all the members came up with demos on their own, which they then presented to one another across an all-night session of drinking, listening and improvisation. The tracks were then reworked or – often – melded together and recorded in a barn in Holland.

If Island of Jewels and The Tower were concept albums about the crypto-fascism of Thatcher’s Britain and Asylum (1985) was a concept album about individuals marginalised and outcast from society, then Any Day Now is a concept album about… disillusioned sea-faring idealists in a post-apocalyptic theocracy? Something like Waterworld (1995) set in the Vatican?

Okay, so it’s not really a concept album and since the album includes songs about: a man who owns a building full of holes with little heads in; neon mariners who seem to be stuck in a purgatory resembling the inside of a can of sardines; the fiscal hypocrisy which underpins the Catholic Church – it is understandable why it’s not an album you would go to with a view to making sense of a break-up (The Lovers) or chuckling at the follies of consumer-capitalism (Faces in the Fire, 1984) or even something more ambitious like conducting a black mass (Basilisk, 1983) or gaining a deeper epistemological understanding of cosmology (The Maria Dimension, 1991).

But Any Day Now is hardly the first example of the Dots producing an obscure piece of work and certainly wouldn’t (and definitely won’t) be the last. The ‘Chemical Playschool’ compilations often contain tracks too awkward, lumpy or just plain weird for the regular releases and nothing on Any Day Now is quite as peculiar as, say, ‘Glad He Ate Her’ on Chemical Playschool 3 & 4… it just seemed unusually hard for me to get my emotional hooks into lyrics like “Cut glass cathedrals slash holes in the air so it always is raining when we kneel down in prayer” or “They’re peeping at the methylated man who spits in a can, spreads his hands for silver, pans for gutter gold”, however evocative.

‘Casting the Runes’ opens, like Cardiacs’ A Little Man and a House and the Whole Wide Window (also 1988), with a portentious chord upon the keys; but while A Little Man’s opening salvo ascends to medievalist pomp and pageantry, the Dots choose to descend to a gloaming synthscape of wind and curdled violin. An almost aquatic bass snakes along below, sending up little sparks and ripples to the surface. These things can best be caught on headphones. Edward enunciates clearly, high in the mix. The song builds so imperceptibly that it is almost forbiddingly seamless – the band leave no chinks in the armour through which a listener might worm their way. Some ghostly back-tracked and layered female vocals manifest themselves at the 3:30 mark, but otherwise the song spirals and repeats in such a way that it would be easy to put it on loop and struggle to know when to turn the record off. Each line of Ka-Spel’s lyrics folds into the next in fatalistic enjambment. ‘Casting the Runes’ is the kind of song that is really hard to sing along to, since you always start singing just half-a-second too late – not that I can imagine tracks from Any Day Now are represented on many karaoke machines here above land.

Musically ‘A Strychnine Kiss’ is not a million miles from Asylum‘s least ambient, more aggressive tracks, such as ‘The Dairy’. However, despite the low-key funkiness of the bass, the staccato jabs of the keyboard, the crisp and snappy rhythm of the hi-hat and snare… the song is surprisingly slow in tempo, almost sluggish. To my ears, the song only really comes to life with the ludicrous, parping sax breaks courtesy of an uncredited saxophonist.

It is with ‘Laguna Beach’ that the album really starts to work for me. It is a modest, even tasteful piano melody with bare-bones accompaniments from keyboard and synth. It sounds like a love song from the lost city of Atlantis and is lovely. The reverberate bass is miraculously aquatic(!) and the little plinkity keyboard motifs and shimmering synth effects evoke Technicolor seashells washed up upon the aural shore. The tonal shift to the markedly less restful ‘The Gallery’ (with an especially affected vocal performance from Ka-Spel) is jarring, though likely deliberately so. The lyrics are absolutely barmy and brought to my mind a monologue from series 1 of Chris Morris’ ambient radio show Blue Jam (1997-1999) in which a man is walled up behind glass as a conceptual art piece. Musically this is another topsy-turvy chamber piece like ‘Fifteen Flies In the Marmalade’ from Asylum, which in turn brings to mind Sparks’ glibly disturbing ‘Under the Table with Her’ from the brothers’ 1975 album Indiscreet. Patrick (Q) Wright plays his violin like he’s strapped upside-down to a waltzer.

Then comes the album’s masterpiece – ‘Neon Mariners’ – a track which Tom has already singled out for praise. Interestingly, the song’s effectiveness does nor reside in either its melody nor its harmonic aspects, neither of which are particularly memorable, but in its tone and atmospherics and its perfect melding of lyrics and sound. Perhaps it’s just the MIDItastic timbre of the music (which, for the record, I enjoy) but this approach to songwriting strikes me as being shared with The Residents, who are on record as saying that they build up their tracks from the quality of individual sounds alone. In this regard, ‘Neon Mariners’ is especially reminiscent of 1990’s Freak Show and 2007’s The Voice of Midnight, in which the music compliments the lyrics like a film’s soundtrack, achieving an radio play-like effect.

Lyrically ‘Neon Mariners’ evokes Coleridge’s ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner‘ (1798), though without following its narrative structure of crime, through guilt, to redemption. Rather, it is as though the moldering and moribund crew of Coleridge’s poem stopped off at a port, went into town for drinks, and found themselves trapped eternally in some neon-lit sailors’ dive. Ka-Spel is not the first artistic visionary to attempt a surrealist re-visioning of Coleridge’s best known work. Chilean ex-pat Raúl Ruiz’s 1983 film Three Crowns of the Sailor thrusts the audience into the company of a bunch of phantasmagorically scurvy seadogs who sweat maggots and, despite being undead, have voracious appetites. There’s nothing quite so grotesque in Edward’s lyrics here, though “drown in seaweed” comes close.

And if the above doesn’t convince you that you should give ‘Neon Mariners’ a listen – it also contains a keyboard patch that sounds like a steel drum!

Then, like a stab of heartburn after a sumptuous meal ‘True Love’ arrives, seizing the unprepared listener by the throat. Tom has already correctly noted that the song builds upon the formula archived on Any Day Now Secrets in embryonic form as ‘Thunderland + True Love Waits’. For relentless, pummeling intensity it also recalls that album’s aptly-titled demo ‘Adrenaline’. Percussion is provided by something akin to bruisingly monotonous siren that beats at the heart of R.E.M.’s plaintive ‘Leave’ from 1996.

This time around Tom and myself are in complete alignment vis. a vis. our assessment of what we think the album’s strongest and weakest tracks are. ‘Neon Mariners’ is the strongest. ‘Under Glass’ is the weakest. As such, Any Day Now is the unusual example of an album which peaks not at its beginning or its end, but in its middle, with the run from track 3 (‘Laguna Beach’) to track 6 (‘True Love’, which we are discussing). Where Tom and I part ways is in our respective interpretations of ‘True Love”s lyrics. Tom feels it is the lover who is hospital-bound and doped on morphine, while I believe it is the narrator. The fact that it is easy for two (pretty attentive!) listeners to come to directly opposite interpretations of the song speaks to the shifting loyalties and squirming interchangeability of dom/sub; sadist/masochist; master/slave in Ka-Spel’s lyrics of this period – a change from the clearer dynamics of perpetrator and victim on Island of Jewels.

‘True Love’ is, at heart, another Ka-Spel track about the interweaving of desire and obsession (‘The Plasma Twins’; ‘Obsession’), focusing on a toxic relationship (‘She Said’), filtered through the lens of a pathological male narrator (‘Thursday Night Fever’; ‘Temper Temper’). It offers a mirror image of The Divine Comedy’s twisted (anti-)love song ‘If…’ from their 1997 offering A Short Album About Love:

If you were a tree

I could put my arms around you

And you could not complain

If you were a treeI could carve my name into your side

And you would not cry,

‘Cause trees don’t cryIf you were a dog

I’d feed you scraps from off the table

Though my wife complains

If you were my dogI am sure you’d like it better

Then you’d be my loyal four legged friend

You’d never have to think again

And we could be together till the end

That said, commentators on ‘Song Meanings.com’ claim that ‘If…’ is “cute”, “funny, honest and sweet” and a “great song for valentine’s day”, so it seems fair to say that interpretation depends upon the listener!

‘The Peculiar Fun Fair’ is but a 30-seconds interval. To be honest, I was a bit disappointed that a song with a title which implies Tim Burtonesque eepie-creepiness wasn’t a bit more peculiar.* In fact, the off-kilter oompah organ only starts 19 seconds into the song. Thankfully avant-garde Liverpudlians a.P.A.t.T. achieved what I wanted ‘The Peculiar Fun Fair’ to achieve with the troubling ‘Fairground Abuse‘ from their magisterial 2008 album Black & White Mass.

Home stretch now. ‘Waiting for the Cloud’ is a dreamily bug-eyed nuclear fantasia with lovely rolling synths and tinkling keyboards that glisten like fairy lights in an underground tour of White Scar Cave. The keyboard refrain becomes a little more insistent at the 4-minute mark, with a John-Carpenter-like urgency. This ushers in an extended bridge between the two movements of the song, which is a little cloyingly p̶r̶o̶g̶g̶y̶ over-rich. Things get sinister-funky for the third quarter of the song with talk of “crocodiles sprouting wings” and then we return to the elegiac and haunting opening movement to finish.

‘Cloud Zero’ has a more classical piano sound and would nicely soundtrack Herk Harvey’s iconic and spooky 1962 low-fi horror film Carnival of Souls. It’s essentially an ambient, atmospheric work, the kind of track that generally turns up on Edward’s solo albums. Oddly, while the title suggests that the song will be a sequel to ‘Waiting for the Cloud’, lyrically it seems entirely disconnected.

The cassette version of Any Day Now finishes here and, to be honest, ‘Under Glass’ does not feel like a necessary addition to the CD version. It starts off promisingly enough with a weirdo-new wave intro that sounds like The Human League played upon a malfunctioning computer. However it doesn’t progress and becomes a bit of a slog at over 7-minutes. That said, for an album as quietly ambitious as Any Day Now to only have one failed experiment is a deeply impressive achievement.

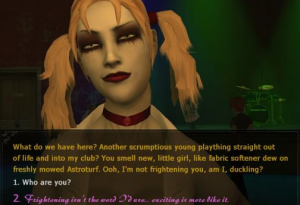

Tom and myself already wrote about ‘The Plasma Twins’ and ‘The Light in My Little Girl’s Eyes’ in our review of 1983’s Legendary Playschool 3 & 4, so I won’t extend an already over-long review by talking about them much here. ‘The Plasma Twins’ is the Dots in full-on gothic splendor and with lyrics like “I’ll meet you at the blood bank. They could pump you into me… It’s only fair because you know I like pumping into you” I can’t help casting my mind back to Troika Games’ seedy but guiltily enjoyable 2004 RPG suck-a-thon Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines. ‘The Light in My Little Girl’s Eyes’ is a mini epic nighttime odyssey like the “Circe” chapter from Ulysses. The music is dreamy but compulsive, with some ‘triffic drum fills.

The Dots’ Bandcamp adds a re-worked version of ‘Neon Gladiators’ to the tail end of the album. It is more organic than the original, but I feel the synthetic sound of the version on ‘Chemical Playschool 3 & 4’ suited the subject matter better. This seems like more of a work-out for Wright’s violin and Barry Gray/Stret majest’s electric guitar, which are admittedly blistering.

*For the record, the same complaint I have about Netflix’s Stranger Things.

Nothing on Any Day Now Secrets is vital unless one is a dedicated Dots fan or connoisseur. Essentially Any Day Now managed to successfully elaborate and improve upon the sketches contained within these demos. However, the album did make for a remarkably good substitute soundtrack for the narrative naval exploration game Sunless Seas (Failbetter Games, 2015). It all sounds very sea-sodden and faintly eldritch already, but it really comes to life with you are transporting crates of spiders’ eggs across the waves or firing a torpedo at an “Auroral Megalops” or cannibalizing your shipmates.

‘Shiver Me Timbers’ sounds like a sample from a MIDI version of a Portishead track on loop, but significantly more enjoyable that what you are currently trying to imagine. Otherwise: if a James Bond theme was performed on toy instruments. ‘Engletje’ has a title like an Aphix Twin track and coincidentally sounds like the more ambient work on his Drukqs (2002). ‘Jah Tension’ is reedy and weirdly similar enough to the music in the dwarven mine in retro PC/Amiga adventure game Simon the Sorcerer (1993) that it made me feel nostalgic in a dislocated, bittersweet way. Maybe it’s a quality that adheres in the track, but it makes me feel really odd!

‘The Cruel Sea’ sounds like nautical to me than spacey, but I suppose if you’re in a submarine at the bottom of the sea there’s little difference. It *does* contain a sound rather like Brian Eno’s Window start-up noise though! ‘The Lounge’ is a nightmarish piece of bossa nova. It would be David Lynch’s favourite Legendary Pink Dots track. ‘Session 55’ is the merest sketch of video game arcade funk. ‘Half a Minute’ reminds me of subterranean pixel horrors of the original Metroid (1986). ‘Adrenaline’ is a little bare-bones, but does succeed in being anxiety provoking.

Any Day Now Secrets shows a great album in embryonic form and captures something of the aesthetic of home videogaming in the late 1980s and for this it should be commended.