Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

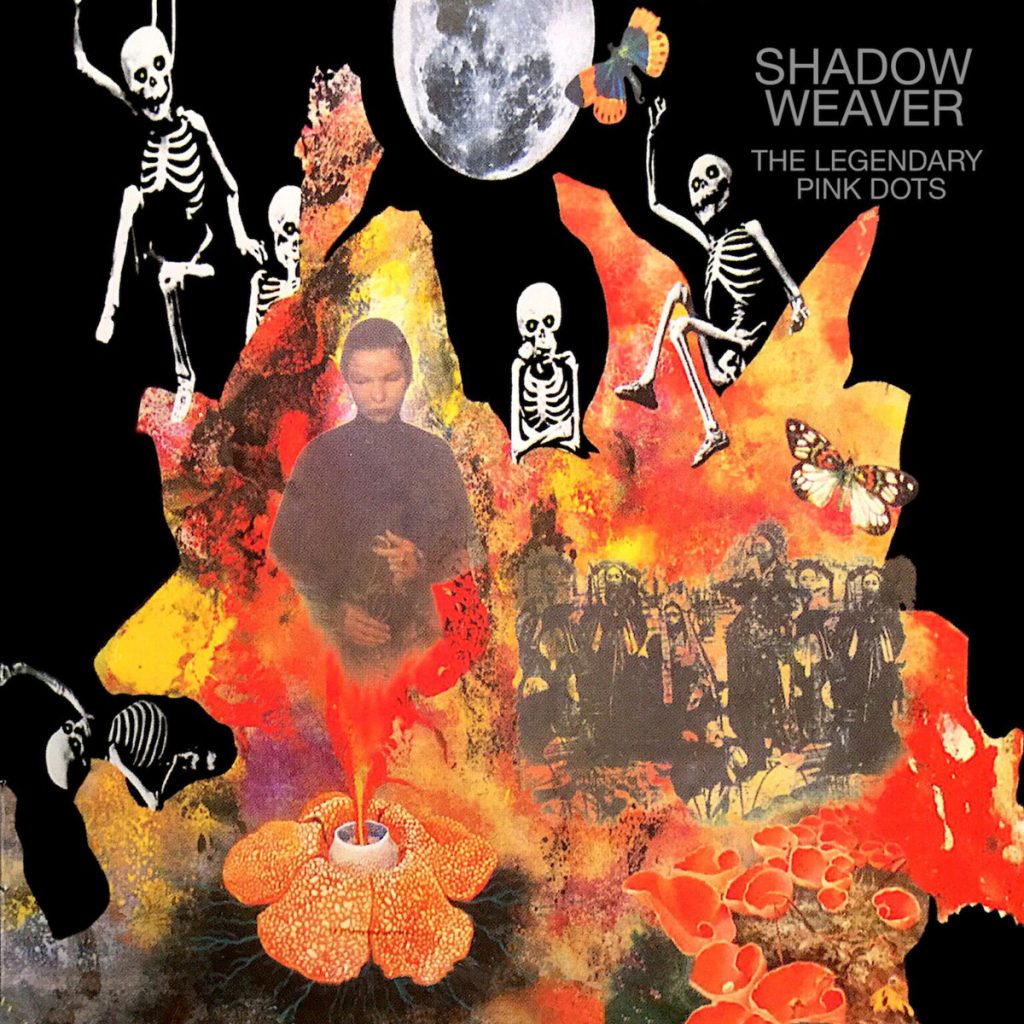

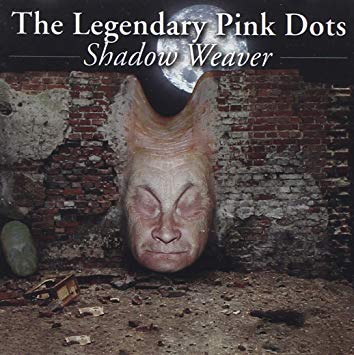

Shadow Weaver (1992)

Tom: When first listening to this album on holiday in Madeira in early September, it didn’t particularly strike me as notable. Especially in comparison to the ornate, focused world of The Maria Dimension (1991). But, over the months, playing this as I have walked to and from Northumbria University, having commenced my three-year PhD study of the BBC’s Play for Today series, it has edged its way into my consciousness and its qualities are clearer.

‘Zero Zero’ elicited an immediate thumbs-up, even in September, as it is blunt and hilarious: “We made a graph, we chanted [indistinct bellowing]”. Then we have the intriguingly bizarre mishmash of worldviews and myth systems which form a ‘person’s’ full name that out-Enos Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno himself: “Omni-padni-Disney-iceman-acme-Leary-Marx-Illuminatus-Christus Clarke…” The song evokes the pull of John Locke-style guidance, the cultural focus on reasoning and finding causes and effects: “We try our damnedest to explain the reasons why and how and when are where… We’re getting nowhere. No doors deep inside this corridor of space and time. If space and time exist […]”. Quarks rub shoulders with flying saucers. Do we ask questions and observe or do we just feel and experience?

“Are you listening?” / “No chance” is one of the great LPD refrains: insidious, doubting, sounding like it has been perennially muttered into the wind, dolefully. The musical timbre is a delicate, plangent wash, with deft acoustic guitar, bare synth pads, slivers of lead guitar and a wonderfully counter-logical – counter-cultural – wah-wah guitar sound. It earns its near-eight minutes, with the last few minutes feeling like an expansion and refocusing of the pastoral psychedelia Pink Floyd were aiming for on Meddle (October 1971).

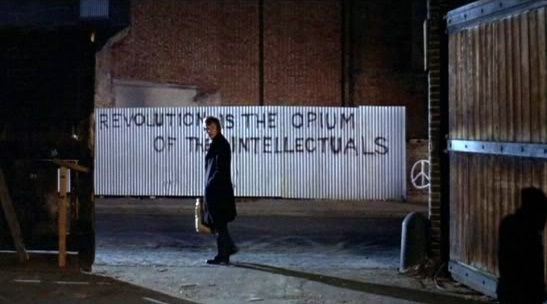

‘Guilty Man’ is a whirring, inexorable grid of percolating sounds that burrows its way into your mind; at first annoying, later compelling. Its musical palette is all mechanical gloom and its scenario an unending incarceration, full of paranoia – “They spy on me, they spike my tea” – and the looming absurdity of “an ape with a stick, he’s bigger than me, complains that he’s sick of my story”. Initially, I didn’t take to this, but it is a proverbial ear-grub of Cold War melodrama, the year after the dissolving of the USSR. It brings to mind the charged, bleak imprisonment of Imre Nagy in Márta Mészáros’ The Unburied Man (2004) or Israel’s captive Palestinian in le Carré’s The Little Drummer Girl – currently showing as discomforting Sunday evening viewing on BBC1. The guitar is coiled-up, serpent-like and simultaneously sharp and fuzzy, similarly purposeful as on The Maria Dimension. I can’t have been ready to listen to this on holiday; subsequent deeper listening has revealed a cumulative power: “Guilty! YOU’RE GUILTY!” renders law as absurd, a Kafkaesque farce, amid animalistic applications of brute power and psychological manipulation.

‘Ghosts of Unborn Children’ questions Disney’s “never, never land”. It is a hazy, low-key, beat-less, drifting ‘ballad’-come-processional confessional. “Oh what I’d give to… be alive… For just one second… I’m nothing.” It seems to detail the dissolving and vanquishing of the ego, possibly following the interrogations of ‘Guilty’. Then, from 4 minutes in, we have the doughty, insistent yet rueful emergence of a new melody. New/old, 1970s futurist/medieval, forward-looking/ancient improvisations. A revolution from out of Sherwood Forest with significant aural echoes of Paddy Kingsland’s great score for the children’s drama serial The Changes (1975), adapted from Peter Dickinson’s tale of anti-technology luddism breaking out in Seventies Britain, which is also, as Peter Wright has argued, a rare idealistic statement in favour of multiculturalism.

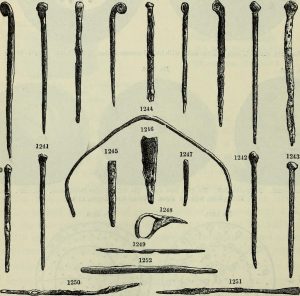

‘City of Needles’ begins with a sound-poetry-like indistinct swarm of gabbling, hissing voices. This is still a track that has not fully won me over. More dystopia: “No survivors! No survivors!” sampled from somewhere and clearly evoking the early-1980s dread the LPDs’ initial sound was rooted in. Whizzing, science-fiction sound-effects; a chugging, waddling electronic rhythm. It’s not the first time we’ve heard Ka-Spel using a tour-guide style address, advertising macabre activities: “Take a light speed spin down headless hole / And feel the deprivation. / We offer benders in the blenders / Red hot pokers in the eyes! / Yet we guarantee you’ll all survive…” We then face a lot of clattering and repetition, to not especially remarkable ends.

‘Stitching Time’ seems to mark, hark, the return of Patrick Q. Wright! Great stuff! It continues the slightly less synth heavy sound of this album and it is good to hear that quailing violin again. There’s ambling acoustic guitar, as on ‘Zero Zero’, if not quite as evocative.

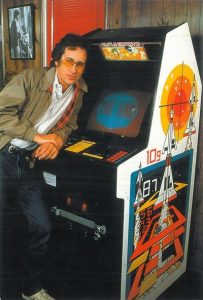

We have lines that call to mind Basil Bunting or Alan Garner, or even anticipate Philip Pullman, three years hence: “And I’m written in stone, I’m the dust on your carpet, a guest in your home – because that’s where the heart is”. This latter phrase has occurred at least once before in our story. So many phrases are pregnant with polysemy: “The rules of the game” – LPD seem to exist as an interstitial bridge of continuity between the sort of children’s games and songs captured in the Iona and Peter Opie’s The Language and Lore of Schoolchildren (1959) and gamer culture of the 1980s onwards. Or, are they seeking to provide a crossing from Jean Renoir’s highly valued 1939 film to Ballard’s fictions, with characters’ internally-defined rules amid societal breakdown? There’s an evocative posing of questions, though also a sense that questions may not be possible. I’m brought to mind of Steven Poole’s review of Martin Amis’s reissued 1982 book on video games and particularly Missile Command, a ‘masterpiece of cognitive panic’ where the player uses ICBMs to shoot down nuclear missiles – with the only, grimly inevitable, conclusion.

‘Twilight Hour’ starts all hazily celestial before seguing into low-end digeridoo-esque droning procession. “Slave chained half naked along for the ride / Catching flies with my eyes shut, my mouth’s open wide…” We have dolorous saxophone joining in to mark a distinctly Conradian journey. “I’m thinking of you / My regret overflows / But sleep softly, my dear one / ‘cos you’ll never know […] This bird’s going to sink / And we’re all going to die!” Does he detail the progress of an awry Ballardian plane – The Unlimited Dream Company – or a boat from colonial times? Neither of these last two tracks are masterpieces, but are chastening soundscapes that feel imbued with cinematic detail.

‘Twilight Hour’ starts all hazily celestial before seguing into low-end digeridoo-esque droning procession. “Slave chained half naked along for the ride / Catching flies with my eyes shut, my mouth’s open wide…” We have dolorous saxophone joining in to mark a distinctly Conradian journey. “I’m thinking of you / My regret overflows / But sleep softly, my dear one / ‘cos you’ll never know […] This bird’s going to sink / And we’re all going to die!” Does he detail the progress of an awry Ballardian plane – The Unlimited Dream Company – or a boat from colonial times? Neither of these last two tracks are masterpieces, but are chastening soundscapes that feel imbued with cinematic detail.

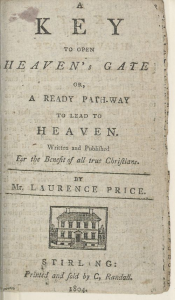

After the grim voyage, the epiphany. ‘The Key to Heaven’ is more panoramic and has that occasional LPD pop sensibility, bursting out of its chrysalis like a John Barry film theme into a dull European Research Group world. This is exactly what we want! Dainty, ersatz harpsichord notes. Absurd call-and-response keyboard sounds around the 3-minute mark. Resounding, gliding loops of wah-wah guitar. A staunch, memorable ear-spider of a chorus – “Think I’ve found the key to heaven / But I cannot find the door…” – rightly rendered again and again. Then there’s a clattering freed jazz freak-out to the close.

‘Laughing Guest’ begins with birdsong and, of all things: that rarity in the LPD oeuvre: a flute. This is a curious tune with echoes of folk music, but closer to Syd Barrett’s damaged psychedelia taken into science-fiction stratospheres: “Squashed in a case where we’re all created equal / Somewhere they’re laughing, they’re planning the sequel / They came from the stars then they all went home”. This askew song fades out and a section of throbbing sound effects and squealing phased voices enters. We hear gadding, atonal lead guitar. Ka-Spel intones: “Consciousness explodes…” We’re almost in early Chemical Playschool terrain here. Then, it finishes with a mix of birdsong and possibly distant arcade gaming.

Then, ‘Prague Spring’, which, in its title, is a rare direct allusion to the events of 1968 which so colour the Dots’ contextual background. Patrick Q. Wright is, crucially, present for this rueful Cold War ballad without words. Circling piano notes, low brass tones and delicate violin dovetail in a superior concoction of sad grace and brevity. Flowing from the 1960s psychedelia of ‘Laughing Guest’, there is a distinct hint of the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s (unfinished) conceptualisation of ‘Acid Communism’, included in the brilliant new doorstopper anthology, K-Punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher. Fisher outlines a view of human life liberated from the drudgery of overwork. He explores tantalising past possibilities to help us combat the still hegemonic Thatcher-Reagan initiated ‘Capitalist Realism’, which was trialled in Pinochet’s Chile from 1973. He draws from the best of the 1960s counter-culture; citing Danny Baker’s childhood holiday epiphany, The Beatles’ ‘I’m Only Sleeping’/‘Tomorrow Never Knows’/‘A Day in the Life’ triumvirate, Jonathan Miller’s Alice in Wonderland (BBC, 28/12/1966), The Temptations’ storming ‘Psychedelic Shack’ (1970), student-worker alliances in the 1970s UK Miners’ Strikes and, more broadly, the exemplar city of Bologna in the 1970s.

‘Prague Spring’ ends with the merest hint of fuzzy lead guitar, snuffed out too soon like Dubcek’s reforming ‘Socialism with a Human Face’ programme of April 1968. But, as Fisher argues, we can build on some of the best currents of the socialist (Czechoslovakia, Chile) and counter-cultural past, and reanimate dreams and ideals beyond the dulling cult of the nine-to-five consumerist work ethic.

Finally, ‘Leper Colony’ is eased in by plangent synth chords. “Does my eye offend you? Should I roll it down the hill?” This scenario of plague and quarantine has a suitably queasy musical accompaniment. There are a woman’s desperate, subdued calls to “love me”, then bee-buzzing strata of sound as it all gets giddier and freer in form. It gradually fades away.

1992 saw a crushing defeat for mild social democratic Labour in the UK, with Kinnock’s party losing to the grey man himself, John Major. John Smith, who styled himself as a sober bank manager, took over and presided over a considerable rise in Labour support following the Conservatives’ disastrous “Black Wednesday” on 16 September. 1992 saw globalisation in the ascendancy but many Tories would never forgive Major or the EU for their ignominious exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. 1992 also saw the Legendary Pink Dots in at times full-on Left Melancholy mode; Shadow Weaver is a fine, doubting record, taking psychedelia forwards, if not with much optimism.

Adam: While the Legendary Pink Dots have always been too phantasmagoric to be categorised as a strictly political band, albums like 1982’s Atomic Roses, 1984’s The Tower and its quasi-sequel 1986’s Island of Jewels, as well as later releases like 2004’s Poppy Variations, have considered the individual in relation to his, her, or their environment – sometimes as a product of it, sometimes adamantly up against it – but always inextricably intertwined with a keen sense of space and place. While 1991’s The Maria Dimension offered something of a spiritual odyssey, in tracks like ‘Pennies for Heaven‘ and ‘Third Secret‘ spirituality was set in dialectic against the more material concerns of institutional religion. With the Dots:– as above, so below. In many of these reviews Tom has situated the Dots’ releases within their cultural-historical contexts, relating their thematics to various rumblings in the zeitgeist.

How then to approach Shadow Weaver (1992)? The album is perhaps the most hermetically sealed Dots release reviewed this far as part of the Legendary Pink Dots Project. Shadow Weaver locks the listener up inside the head of some kind of neurotic psychonaut, cosmic obsessive, nomadic alchemist… for a good hour. To assess whether you can stand to be trapped inside the skull of such a fellow you might wish to consider your tolerance for late-night drinking sessions with philosophy students. If you would find such company utterly intolerable, I suspect you’ll struggle here since Ka-Spel’s lyrics are at their most inwards-looking. I don’t believe he’s ever before used the first-person pronoun to such an extent as here before: “I roll boulders up mountains. I hang on a cross. The original sinner, I’m counting the cost”; “Did you hear me crying in the night that lasts forever? Did you see me reaching out from Never Never Land?”; “I shaved off my hair ‘cos I found it amusing, I faked my despair in the beautiful ruins…”

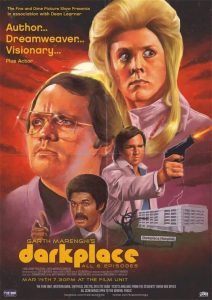

If this reads like po-faced self-parody, I suspect it’s deliberate. I’m reminded of Matthew Holness as Garth Marenghi introducing himself as: “Author; dream weaver; visionary.” As Marlowe with Dr. Faustus before him, Ka-Spel recognises that man’s pursuit of knowledge (-especially when it is a man-) often leads to narcissistic navel-gazing. There is as much bathos in Shadow Weaver as there is pathos. However, I do not believe it is a coincidence that my favourite track is ‘The Key to Heaven’, which establishes some vivid and typically phantasmagoric imagery (“They recycled all the cripples”; “they’re propping up our front line, but behind them is a plague”) before the narrator starts talking about himself.

In fairness, if thematically and lyrically Shadow Weaver and its companion album Malachai (1993) represents something of a cul-de-sac for the Dots, it is an inevitable and likely necessary one. The Maria Dimension was uniquely concerned with how, to quote Terence McKenna, “culture is not your friend” since its institutions will quickly commodify any personal spiritual revelations the individual is likely to have. Religion builds walls and rituals; inner-exploration breaks these down.

Creative Commons

However, music is rooted in the communal experience and the core of most artistic expression is the desire to communicate. In the words of Tennessee Williams: “Personal lyricism is the outcry of prisoner to prisoner from the cell in solitary where each is confined for the duration of his life”. Never before have the Dots seemed so sceptical about the ability of the individual artist, seer, truth-seeker or visionary to break down the door of their personal cell and actually bridge the gap between persons.

The experience of listening to Shadow Weaver would be intolerably suffocating therefore if it weren’t for the fact that its dreamy, psychedelic and often expansive music counters this lyrical tendency towards the solipsistic. ‘Zero Zero’ begins with a clapping jackboot stomp, but rather than building to the industrial Cabaret Voltaire-like track one might expect, instead becomes a thing of quietly swelling synths, with Niels Van Hoorn’s swirling, searching woodwind almost seeming to “give voice to” the ineffable questions which encircle its narrator. It’s certainly lovely and plaintive, but – like much of the album – it’s a song to soak in and then wash off, only lingering like the steam and buzzing headache after a hot bath. I’d be hard pressed to hum it, let alone sing it. ‘Guilty Man’ could, in 2018, be convincingly covered by Ross and Reznor’s incarnation of Nine Inch Nails, all crunchy sledgehammer guitars and doom, but as conjured to life by the Dots in 1992, slithers quietly along, belly close to the ground and its tongue in the listener’s ear; spit-whispering its insinuations of guilt, never screaming them. ‘Ghosts of Unborn Children’ is similarly quiet, its notes almost strung out to oblivion so that space yawns within the music – eldritch noises only reaching you as through water at a distance. It’s too arresting to be boring, but too nebulous to truly get under the skin… until the last four minutes, during which we are teased with some screwy counter-melodies and instruments that my untrained Western ears hear generically as “Oriental”, but may be a bansuri or khamiso or else the timbre of those instruments cleverly imitated by Van Hoorn.

‘City of Needles’ literally does start with whispering, which becomes so over-layered it sounds like the buzzing of insects. It reminds me of the more ambient tracks from 1985’s Asylum, like ‘So Gallantly Screaming’ or ‘This Could Be the End’, but without the hallucinatory edge those tracks contained. Those soundscapes sounded as though they were rooted in the concrete world – dredged out from a swamp in the case of ‘TCBtE’ or picked up from scattered television broadcasts in the case of ‘SGS’ – whereas ‘CoN’ is a self-directed monologue that could only ever belong to a psychic, inner space. ‘Stitching Time’ is slightly easier to get a handle upon, thrumming and chiming and gloaming like the druggier outposts of the British folk revival: Third Ear Band, Quintessence or even Comus. It becomes remarkably sparse at around 3:30 minutes in, with just Ka-Spel’s voice exposed against a backdrop of hand drumming. ‘The Twilight Hour’ is united with ‘Stitching Time’ in the version of the album provided on the Dots’ Bandcamp page, presumably apropos to them sounding like two pages from the same enchanted book. Considering the resolutely morbid tone of the album this book might well be pictured as the Necronomicon or some other bedeviled grimoire. The song actually seems to use the “ghost voice effect” I like to use in Audacity, a sinister reversed reverb also used to unintentionally hilarious effect on the options and save selection screen of 1998 horror point-‘n’-click game Sanitarium, now available for iPhone!

‘The Key to Heaven” is, as mentioned, my favourite track. While I have already praised the lyrics, my preference mostly derives from the fact that it contains the kind of off-kilter, potentially-irritating sounds that I expect from the Dots and as a fan of The Residents. It’s still not a barn-stormer by any means, but it has a kind of skew-whiff funk to it that is only accentuated by Van Hoorn’s parping horn. The more times I listen to it the stranger it seems, though it might have made a similarly weird bedfellow to Rick Wakeman’s contributions to the soundtrack of Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion (1984), maybe suggesting that this is the one track on the album that really sounds like a throwback to the Dots’ ’80s sound. Certainly ‘Laughing Guest’, by contrast, is far more within the struck-out psychedelic mold of the Dots’ work of the 1990s. It burbles along in sleepy-sinister fashion, refusing to rush to an easy resolution. I don’t feel I’ve provided myself with the ideal listening experience for the track yet. Much of this album really does require a darkened reading room heavy with incense or, a grove within a forest, or even, yes, a graveyard. It is not an album you can enter upon half-heartedly and then hope to be rewarded by. Even a more conventionally rewarding track like ‘Prague Spring’, which recalls the haunting acoustic ballads of Four Days (1990), refuses to provide the emotional peaks and troughs of, say, ‘The Lovers (Part 2)‘ or ‘Golden Dawn‘. Even final track, ‘The Leper Colony’, escalates to a dissonant crescendo and then burbles and falls in upon itself and fades out. Listeners are left perplexed and suspended, hanging unresolved to wait upon the release of Malachai aka Shadow Weaver Part 2 the following year in 1993, which Tom and myself are also going to get to ourselves this next year coming!

Postscript: For those of you left especially intrigued by this album, the Dots have also kindly provided on their Bandcamp a series of unreleased sketches and improvisations recorded around the time of Shadow Weaver, with the title Come out from the Shadows. It is non-essential, but terribly intriguing and would provide great furniture music for a haunted lounge bar.