Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!—

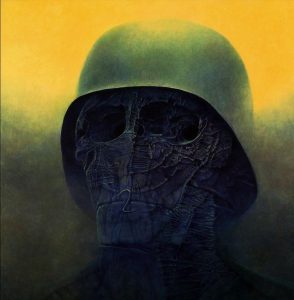

Adam: A boy grows up amidst the ruins of a world war, alongside the genocide of many of his country’s citizens. As a man he becomes an acclaimed artist, finding critical repute both at home and abroad. He keeps working as his wife falls victim to cancer and his son to suicide. Even as he ages he stretches out into new mediums, forging new collaborations. Then, at the age of 75, he is stabbed to death by a teenage boy for refusing to lend him a small sum of money.

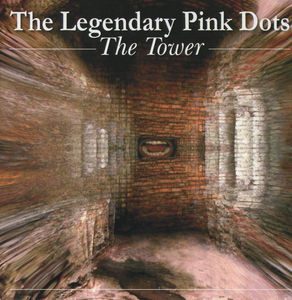

This is a potted biography of the late Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński, but in its casual, meaningless awfulness, its insipid tragedy, it could also be the story of any one of the anonymous suffering denizens of L.P.D.’s The Tower. Beksiński’s son, Tomasz, was a huge Legendary Pink Dots fan – so, after his death, the band used his father’s digital paintings as covers for their reissued albums. The Tower specifically is dedicated to the memory of both Tomasz and Zdzisław.

Zdzisław’s cover for the album is of a vertiginously-blurred brick corridor ending in a screaming mouth encased in a wall of bricks, recalling the claustrophobic ending of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Cask of Amontillado‘. It is difficult to tell whether this mouth is contorted in a scream of defiance or a scream of anguish but after a certain time of imprisonment it is probably hard to tell. Zdzisław’s paintings are usually all elbows and cobweb flesh, but the digital art provided for The Tower‘s lyric booklet, depicting an inscrutable chimney-like tower stretching up into the Heavens in an isolated pastoral wasteland, is unusually stark and simple. The booklet prints the album’s lyrics twice, once in English, once in Polish.

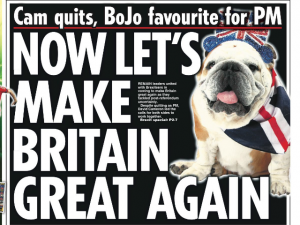

On a day in which cards printed with hate speech have been slipped under the door of Polish residences in Huntington following Britain’s inglorious vote of exit from the EU (the so-called ‘Brexit’) it is moving to see this gesture of goodwill towards the band’s East-Central European fanbase. Of course, the Dots are emigrants themselves, Ka-Spel having moved to Amsterdam in ’84 a year ahead of his remaining bandmates. According to Ka-Spel on the album’s Bandcamp page, the ‘Tower’ specifically refers to the Tower of London and the genesis of the project came when he saw then prime minister Margaret Thatcher talking on the television about her “good friend Mr. Pinochet”. Edward reflects; “At that instant you kind of sensed what this monster really wanted to do with the rioters, anarchists, welfare seekers, travellers, punks…” However, despite its specific concern with a very English stain of fascism, The Tower belongs to an East-Central European tradition of bleakly absurdist parables that critique the oppressive authoritarianism of the state and champion the [squashed; petty; compromised] humanity of its denizens, whether conformists or dissidents. This is the tradition that the late animations of the wonderful Czech animator Jiří Trnka fall into – The Cybernetic Grandma (Kybernetická babička, 1962) with its dystopia of robotic care replacing maternal love; or The Hand (Ruka, 1965) in which a potter is forced to produce endless clay totems of a sinister gloved hand. We might think of the bleak, absurdist science-fiction of Polish fabulist Stanisław Lem, where euthanasia programs exist alongside bureaucratic mishaps. Although The Tower is clearly indebted to Orwell’s 1984 (with its image of the future as a “boot stamping on a human face forever”) it might equally be linked to Yevgeny Zamyatin‘s We of 1921.

That is to say, Ka-Spel is working in broad, allegorical strokes, but that does not stop The Tower from being a churning sucker-punch of an album. It is ugly and flinty and not a whole lot of fun, though an alien with sufficient distance from the sufferings of humanity might find it blackly humorous. It is the most tonally and thematically tight release by the Dots up to this point and has the [arguably] ideal album length of 42 minutes, the same as Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

It starts with an unpleasant electronic buzz of the kind found on a Bauhaus, Cabaret Voltaire, or Throbbing Gristle album, as though the album is a machine revving slowly into gear. The pitch increases and then abruptly stops, replaced with a keyboard melody and what is immediately striking is the clarity of the sound. Gone is the comforting, shrouding murk of the very early Dots. We’ve moved into a new territory of sharp production and clearly demarcated instrumentation that allows Ka-Spel’s lyrics room to be heard and decoded. The song structures have become more traditional, albeit underpinned by curious rhythms and peppered with spacey sound effects. Meanwhile, the long and ambitious soundscapes are mostly reserved for Edward’s solo releases. You’d tap your foot if ‘Black Zone’ wasn’t about militant fascism.

One thing I admire about The Tower is that it manages to utilize fascist imagery (skulls-and-crossbones; numbered tattoos; military insignia) and jack-boot rhythms without being seduced by the rage, hate and disciplined uniformity that fascism offers, which other industrial bands of the time (such as Whitehouse, Throbbing Gristle or the Slovenian band Laibach) and today (the sneering industrial-lite Fat White Family) flirt with. The fascism depicted in The Tower is undoubtedly powerful, but it is never cool. It is the fascism of red-faced, brandy-slurping generals and scowling, morally-righteous wife-beaters in white shirts and black trousers and rubbish little pamphlets and mean little sentiments and short-sighted pride and fear. Ka-Spel never truly inhabits and expresses the voice of the fascist (as Roger Waters does with the neo-Nazi Pink in The Wall) but narrates wryly and ironically, slipping in and out of different registers, allowing for a distanced, bruising view.

The particular dystopia conjured by The Tower is Nazi medieval-futurist. There are gangs of state-endorsed thugs on the streets; deviants are rounded up and exterminated; kitsch biscuit tin nationalism (Czech dissident Milan Kundera once described kitsch as “the folding screen for death”); people with biblical and Old English names spoken like incantations (Salome, Algernon, Astrid); knights and nuns and stormtroopers. But the music is as synthy as a John Carpenter soundtrack and ominous metaphysical place names like ‘The Black Zone’ seem charged with technofuturist magic or merely nuclear fallout. A connection is being forged between the myths of Old Albion and King Arthur and modern-day nationalism. To quote Edward from a wonderful 1987 interview with Snowdonia Magazine:

“The Tower” itself musically as well as lyrically reaches back to the time when the Tower was a political prison, in the Middle Ages. But it’s mixed with futuristic overtones; ultimately you get something which is timeless, ‘cos that was always another thing about the Pink Dots: we destroy the concept of time, I suppose in a way like the surrealist paintings.

As for the titular Tower prison complex itself, it is not described in any great detail. It certainly seems inhospitable. Pillows are stuffed with pins and flies abound. Punishment may be sealed off from the public arena, but it remains ritualized and performative, concerned with inscribing power upon the bodies of the prisoners, recalling the tattooing torture machine of Kafka’s ‘In The Penal Colony‘. One imagines Jeremy Benthan’s Panopticon, a “mill for grinding rouges honest”, in which a single elevated watchman observes all the prisoners, who do not know when they are being watched. Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish (1975) sees the model of the Panopticon as having extended to modern surveillance societies: “one can speak of the formation of a disciplinary society in this movement that stretches from the enclosed disciplines, a sort of social ‘quarantine’, to an indefinitely generalizable mechanism of ‘panopticism'” (p.116).

The lyrics to ‘Tower 1’ suggest an endless theatre of punishment. “No-one has the key to the Tower” Edward intones somberly. There is no parole. No possibility of freedom. It is all punishment, no grace. No forgiveness possible. Indeed, the punishment itself becomes self-sufficient ~ “no-one names a crime committed, no-one blames a soul.” As with Kafka’s bureaucratic satire The Trial (1925) guilt is non-negotiable. The condemned are guilty by virtue of the fact that they are condemned and it is all just grist for the machine. After all – as the logic of the Prison Industrial Complex goes – if there are prisons, then there have to be prisoners. After all, what else are the guard supposed to guard? The rulers of the L.P.D.’s imaginary dystopia will be very pleased to know that scientists are investigating the possibility of developing drugs that make prisoners feel they are experiencing millena of imprisonment in just eight minutes. After all, Dr. Rebecca Roache soberly informs a journalist, this will all be much cheaper on the tax-payer! We could, ideally, create Hell on Earth, making the thousand-year sentences for sex offenders that Vanessa Place critiques in her provocative The Guilt Project: Rape, Morality and Law a livable reality. While I would hope and assume that Ka-Spel doesn’t consider his merry band to be deviants a la sex offenders [he is not a man I would expect to be interested in wielding power over another] he certainly sees himself and his friends as the kind of undesirables that would end up locked away in the Tower, listing ‘April, Philip, Roland, Barry, Sally, Patrick’ and himself as prisoners. “Me” he sings plaintively at the end of ‘Tower 1’. “Me me!”

A side-note: Curiously and pleasingly, I discovered that ‘Tower 1’ works remarkably well doubled with Jiří Barta’s 1996 film Golem. Have a look!

Musically The Tower is often less strident and more reflective that one might expend. Certainly, the previously released ‘Break Day’ in full of buoyant messy off-beats and the menacing tick-tock of synths and the sonorous mockery of Edward’s vocals (at times he even sounds like John Maus) keep things mean and oppressive; but the guitar playing is often delicate and melodic and Patrick Q. Pagannini’s violin is trilling, sweet and sad. Lily AK’s vocals on ‘Astrid’ (a track that seems to show the neglectful relationship between two revolutionary fighters from the opposite perspective o that later offered by ‘Shock of Contact’ on 1986’s conceptual follow-up album Island of Jewels) are almost heart-breakingly delicate and reproachful. There are little baroque arpeggios and the album is not without its comforting harmonic conventions. In fact, the B-side of the album is, for all its fuzzy synth sequences and stabs of guitars, resigned and surprisingly low-key. Oh~ and parts of it are pretty funky too!

Musically The Tower is often less strident and more reflective that one might expend. Certainly, the previously released ‘Break Day’ in full of buoyant messy off-beats and the menacing tick-tock of synths and the sonorous mockery of Edward’s vocals (at times he even sounds like John Maus) keep things mean and oppressive; but the guitar playing is often delicate and melodic and Patrick Q. Pagannini’s violin is trilling, sweet and sad. Lily AK’s vocals on ‘Astrid’ (a track that seems to show the neglectful relationship between two revolutionary fighters from the opposite perspective o that later offered by ‘Shock of Contact’ on 1986’s conceptual follow-up album Island of Jewels) are almost heart-breakingly delicate and reproachful. There are little baroque arpeggios and the album is not without its comforting harmonic conventions. In fact, the B-side of the album is, for all its fuzzy synth sequences and stabs of guitars, resigned and surprisingly low-key. Oh~ and parts of it are pretty funky too!

I didn’t predict that Britain would choose to leave the EU on June 24 2016, but as I walked to the polling station the day before to vote Remain I braced myself by singing the last lines of The Tower‘s ‘Tower 5’:

You wanted easy answers. You want a tidy end. Don’t you know you’ve got a lot to answer for? You wanted shining heroes. You wanted sparkling knights. BUT THEY’RE GONE. You chose your grave. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there…

Tom:

BRITAIN, an island in the ocean, formerly called Albion, is situated between the north and west, facing, though at a considerable distance, the coasts of Germany, France, and Spain, which form the greatest part of Europe.

(The Venerable Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, 731AD, 1.1)

Black Friday. ‘Black Zone’.

Lumbering, just out of grasp, monoliths of distant synth slither into view on the horizon.

“They cut down all the trees. They put up a sign: keep away from here”. Poison and fission, and ‘enemies’; a distended, inhuman vocal chant in the background.

“Cause the Black Zone’s here to stay…”

Blake’s 7 sound effect, then into the familiar woozy waltz of ‘Break Day’, encountered before in this big story. But not as, from 0:56, with as threatening a buzz of guitar noise. This is well produced.

“You had the brains. You had the money.”

“You recognised the symptoms. Smelt the hatred in the air. But you stayed.”

How many in the North will want to stay in England when they realise the consequences of their decision, and if Scotland obtains EU membership?

‘Tower 1’ deploys its humming, circling guitars, like insects on a bad day.

‘Faculties are failing because they’re really rather old’. I am seeing 60-year-olds, say, Ian Botham, comfortable, cosseted by Keynesian upbringing and good luck/’talent’ into gambling with the futures of the younger generations. All for the sake of a flag: a bundle of rags symbolising pompous entitlement and arrogance. Casting democratic votes to destabilise those younger and more foreign than them. Ah but it’s all right as ‘sovereignty’ had been obtained! There’s been a ‘taking back’ of ‘power’!

Delay-soaked mystery; “No one has the key to the tower”.

“Cousin Julie. Audrey. Johnny. Algernon. Barbarella. Shelley. Napoleon. Winston. Patrick. Ian. April. Philip. Richard. Martin. Gary. Mark…” A middle-class female RP voice (and a secondary male one) reels off a roster of names, oddly. Is it a register? Is it a firing squad roll-call? It is backed by an increasingly fast tempo. A sense of shame and overpowering loss fills the noggin.

“George had the role of the spokesman…” The amazing ‘Vigil-Anti’, with violin gravitas and a step-up in urgency. Jackboot beat. A signifier of the oldest “Discipline”. “Where songs are empty. Words are anti-this, anti-that…” Where the whole of Western logic and thought and ‘democratic process’ can be brought to this: a starkly binary choice that cannot address the complexities. In the context of a media and public discourse that has been beneath contempt.

I feel shivers up the spine. “Smashing the name of the Lord”.

[…] Guilty of spring

and spring’s ending

amputated years ache after

the bull is beef, love a convenience.

It is easier to die than to remember.

Name and date

split in soft slate

a few months obliterate.(Basil Bunting, ‘Briggflatts’, Collected Poems, 64)

“Brave vigilantes… Braaaave vigil-antis… Braaaaaaaiiiiive vigiLANTEEEEEIISSS!”

EK-S’s repetition and intonation do the work far more incisively than any slogan or theory would. These are incredible moments. Then, calm and displaced, ‘A Lust for Powder’ ambles in.

“We’re not alone. We’re not alone.”

But we are, with cocaine neo-liberalism: leading to chaos, no plan, competing and irreconcilable ideas of that being alone means. The inscrutable surface is pierced by a brief hint of church organ, then shifts into…

‘Poppy Day’ – a song I have loved for a long, long time; that haunts the psyche. That was played in mid-set in the Newcastle gig a few years ago, pitch perfect. Grave strings chisel in stone, while that evocative keyboard cycle does an existentialist ring-a-ring-a-roses. Expressing what big calls can be made so weirdly casually.

This song is melancholy and piercing; I have written of it previously, linking it to a Zombies song and the haunted Edward Barnes in the original Upstairs, Downstairs, with its Series 4, its best, focusing on WW1. It manages the seeming incongruity of being both scathing and regretful.

“We’ll remember. We’ll re-member. WE’VE GOT OUR POPPIES ON!”

This is absurd, yet barbed: “We remember how you loved the war films, and hid behind the sofa throwing balls of silver paper.” Then moves into the unsentimental, blunt poignancy of: “You shall not GROW OLD! Cos it’s poppy day…”

Memory played out as public ritual. A sickening, deadening denial of life; beings and voices snuffed out. On repeat, every year.

“We shall not GROW OLD!” Does this bring it into the present, Edward speaking on our behalf? Or is it the voice of the tormented ghosts of dead soldiers?

‘Tower 2’ brings absurdity and ritual torture turned matter-of-fact: “Monkey spat in captain’s face. They cut his tongue out.” There’s the odd, non-melismatic vocal play of: “6.2-ee-ew-ee-ew-ee-ew…” And the interjecting female voice; it prefigures the European Britishness of Sally Timms or Anna Meredith. ‘Tower Towns’ seems to chide the New Towns. “Now there’s Tower complex, Tower Town. Population’s going down, but we’re great again…” This last section is pronounced in a mean lower register; making a leathery, lie-concealing assertion of the sort not uncommon in Britain these last months.

‘Astrid’. This is simply shattering. A female voice takes and claims a whole song, and it’s a shift of perspective towards an abandonment and obfuscation. “Forgetting you is hard… do you forget so easily?” Why has ‘he’ – if it is a ‘he’ – burnt all of her cards? Why has any pretence of a relationship been allowed to remain for so long when it really hasn’t been close?

‘Rope & Glory’. Science fiction lasers – why is it so easy to imagine the young EK-S liking Tom Baker Doctor Who, Space: 1999, Blakes 7, Hitchhikers’ Guide et al…? British science fiction of the 1970s often destabilised the more positive take on the future conveyed in the 1960s through Star Trek. Dystopias are never too far away. INITIALLY, there are hints of ‘Pack Up Your Troubles’ jollity, with EK-S distant, like an old 78rpm record, but, listen to those words…

“Flags are flying in the wind and all the world can hear us. We can take it on the chin and fight another day. The tower’s shining in the sun. Outside the kids are having fun. Soldier lets them stroke his gun and leads the grand parade!”

A martial Britain. A new ‘common sense’ with hate, suspicion, entitlement and bizarre, chauvinistic arrogance all ‘democratically’ validated.

For me, the most memorable moment in Marc Karlin’s film For Memory (1982; shown on the BBC, 1986) was the extended scene of children being involved, or was that indoctrinated, by a National Trust Theatre Company interactive history-play about the Armada, alongside an actor playing Sir Francis Drake, with their spontaneous responses of “Kill ‘im!” and other examples of bellicosity when Franny D. asks them what should be done with a Spanish prisoner they’ve taken… It seemed more nurture and socialisation rather than nature, as the original lone voice became a darkly amusing cacophony of vindictive shouts. They had ‘fun’! Learning about ‘the past’.

Then, a piercing alarm-clock shrill passage into ‘Tower 3’. And there isn’t much time… And it isn’t Pink Floyd, at least not quite. “Keep it pure, keep it white, keep it free from undesirables…” This is rhetoric that is par for the course in dystopian imagined societies, and 2016 Blighty. “Peace Krime’s now suspended” is the most explicitly Nineteen Eighty-Four moment in this LP, which often conveys feelings of paranoia and oppressive surveillance.

“And the patriots stay in as convoys rattle down the street. No-one hears the weeping, no-one listens for the cracks at dawn. The shovelling goes on and on and on. But the patriots aren’t frightened cos they heard it on T.V. that a Golden Age lies ’round the corner. Any day now… Any day now!”

This is an album that, sadly, finds its uncomfortable moment when experienced on 24th June 2016. I don’t want this to be the context, but we have to get feelings out, then think about what sort of country we are, and if anything positive can possibly be retrieved…

‘Tower 3’ spins out into weird psychedelic electronic shuffling with an indistinct sampled voice – just what is going on in this country? A delusional ‘protest vote’, north easterners and south westerners putting two of the biggest fingers up to an international institution which disproportionately benefits their areas.

Sunderland: 61-39 LEAVE. I grew up in this place, and, it’s not so easy as to think it’s all just loads of racists. There are some – BNP and UKIP have had support – and it is a far more insular place than the big cities, but this is more an inarticulate lashing out, an ignorance of what exactly is going on than any hard-core xenophobia. Blaming austerity on EU membership is like blaming the FA for Sunderland AFC’s woeful run of signings pre-Defoe! A tiny majority of people in Sunderland would be able to explain what neo-liberal ideology is, and isn’t that the problem? Not knowing the context for immigration…

And also, perhaps, something in this vote was due to a deep and irrational attachment to flags; to quote Jonathan Meades, do objects have special properties beyond their use?

‘Tower 4’. “Caught up on the crossfire” becomes another uncanny refrain, with siren-like sounds and EK-S’s increasingly whispered, hushed tones.

That violin tolling horrors told: “Sister Astrid, now corrected – never says a word. The list goes on and on. The bombs, the blood… For every guilty death, there’s 20 more. The limbs go flying across the floor, and no-one’s crying anymore. Just caught up in the crossfire – and Jenny wants her child.”

It is all very evocative of the brutalised, civilisation-collapse of Threads, which went out on BBC-2 in September of 1984. Scapegoats, mutilations, ultimately, silence…

‘Tower 5’ is a shattering coda and surely the best ending thus far to an LPD record:

“Wanted easy answers? You wanted tidy end. Don’t you know you got a lot to answer for?”

“You wanted shining heroes. You wanted sparkling knights… BUT THEY’RE GONE…”

“You chose your grave. Now lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there. Lie there… Lie there… Lie there…”

“SING! WHILE YOU… SING! WHILE YOU…”

Gradually, this hazy, haunting Gracie Fields or Vera Lynn brief snippet is used while several final damning imperatives are issued: “lie there…”

“SING! WHILE YOU… SING! WHILE YOU…”

I am brought to mind of the mystery of the northern poet Basil Bunting’s coda to his modernist, fractured epic Briggflatts, and the despair and disorientation of this particular historical moment we are in. “While you…” what? What can we do? I do know that we’ll have to sing, but what else will we be permitted to do?

A strong song tows

us, long earsick.

Blind, we follow

rain slant, spray flick

to fields we do not know.Night, float us.

Offshore wind, shout,

ask the sea

what’s lost, what’s left,

what horn sunk,

what crown adrift.Where we are who knows

of kings who sup

while day fails? Who,

swinging his axe

to fell kings, guesses

where we go? (Basil Bunting, CP, 81)