Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

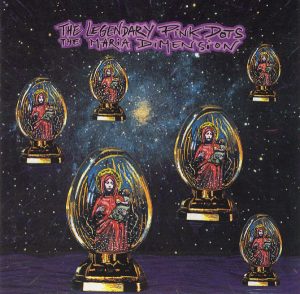

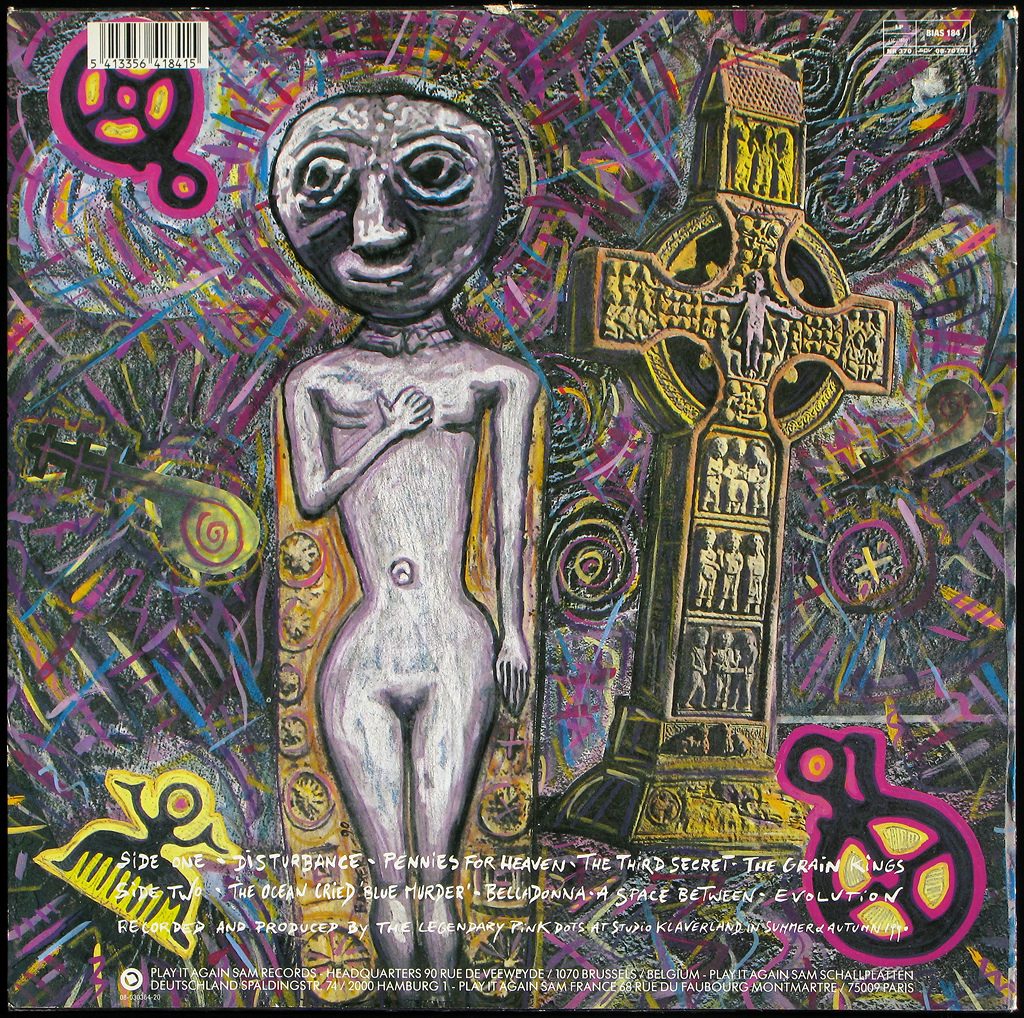

The Maria Dimension (1991)

Cultural Context

Tom: Since we last engaged you with Dots thoughts centring on 1990, Thatcher has gone. February 1991 saw the Gulf War, with the USA and other countries including the USSR uniting to combat Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. The last day of March saw the commencement of the long and bloody Balkan War. The UK was somewhat fraught, with an ongoing recession leading to unemployment rising to 2.18 million by 16 May, above the European average. Worse – for me at the time – this was to be a second year with no new Doctor Who on TV. Better, some injustices were righted: the wrongfully convicted Birmingham Six were released in March and the detested Poll Tax was abolished in April. There were portents of things to come – Tim Berners-Lee introduced the web browser on 26 February and in April plans for a football ‘super league’ were announced, presaging the eventual ‘Premier League’ by 16 months. The British summer of ’91 saw riots in Leeds, Cardiff, Dudley, Handsworth, Oxford and Tyneside. In the summer and after, momentous events were to occur in Eastern Europe…

The UK pop charts saw stunning hits from the Situationist pranksters The KLF – ‘3AM Eternal‘ and ‘Last Train to Trancentral‘, the grandeur of Massive Attack (‘Unfinished Sympathy‘) and an ironically revitalised Queen. Albums released the same month as The Maria Dimension included Richard Thompson‘s Rumour and Sigh (featuring the magnificent ‘1952 Vincent Black Lightning‘), The Wedding Present‘s atypically intense, Albini-produced Seamonsters, De La Soul‘s De La Soul Is Dead, Mercury Rev‘s Yerself is Steam (just listen to the scorching ‘Chasing a Bee‘) and The Smashing Pumpkins‘ raw and ready-ish Gish. March had seen the release of REM‘s massively successful Out of Time, which pointed the way for the 1990s; the old punk generation Georgian band bequeathing conscience and craft to Generation X. The following month The Orb released their Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld album, which famously sampled Generation X favoured poet Sylvia Plath.

What an excellent musical year 1991 was, as evidenced by the variety of my favourite albums of the year: Billy Bragg‘s Don’t Try This At Home – which featured a cover of Neil’s ‘Dolphins’ – Shut Up And Dance‘s Death Is Not The End, Saint Etienne‘s Foxbase Alpha, A Tribe Called Quest‘s The Low End Theory, Ultramarine‘s Every Man and Woman is a Star and My Bloody Valentine‘s Loveless.

Ka-Spel, born in 1954, predates both Generation X and – just – Punk. This album reveals his idiosyncratic development of the 1960s and its psychedelic legacy. May 1991 was ready for a statement of intent from the Legendary Pink Dots, following their audience-doubling The Crushed Velvet Apocalypse; the band were now selling 10,000 records per release. For me, The Maria Dimension is a good deal more enticing and intriguing than its predecessor. The album’s concept is more focused and is enigmatic: “TMD is a place where multiple Marias sit serenely and wave to us as the snowflakes fall. It is not an earthly place.” Replacing TCVA’s often busy and clattering sound palette, TMD sounds much more enveloping and the music is given space to breathe.

Side A

We begin with ‘Disturbance’, which beckons us nearer with digeridoo and fuzz guitar, as Ka-Spel sings of “sweet transparent lunacies”. This is expansive, terminal fairground music, carefully kept down to 5:27. It shows some of the influence of Ash Ra Tempel and early Chrome, as EKS has acknowledged.  ‘Pennies for Heaven’ has stripped-back guitar, like ‘I Love You in Your Tragic Beauty’, accompanying a lyrical exploration of religion and consumerism: “paradise, it has its price”, “Our price, our choice…”, “We’re forced to crawl through needle’s eyes”, “Angels chanted, ‘You can’t take it with you'”. It’s another LPD fatalist’s stomp, with martial bombast provided at the end by synth horns. ‘Third Secret’, coming third, has rueful Utopianism: “Dead eyes searching for messiahs in the stars”, backed by a low-key ensemble of steady drum and dank keyboard. There is again the sense of the religious turning to the worldly: “The priest is passing round the dish, / Our Lady’s selling tissues for the tears”. There’s also history, with haunting references to Erwin Rommel and “hidden cities in Brazil”. While the song gains momentum when synthetic string sounds enter, it isn’t quite as great as it would have been with Patrick Q. Wright’s violin. Still, it is strangely affecting stuff, and ends aptly with the sampling of a creeping old 78rpm recording of ‘Ave Maria‘.

‘Pennies for Heaven’ has stripped-back guitar, like ‘I Love You in Your Tragic Beauty’, accompanying a lyrical exploration of religion and consumerism: “paradise, it has its price”, “Our price, our choice…”, “We’re forced to crawl through needle’s eyes”, “Angels chanted, ‘You can’t take it with you'”. It’s another LPD fatalist’s stomp, with martial bombast provided at the end by synth horns. ‘Third Secret’, coming third, has rueful Utopianism: “Dead eyes searching for messiahs in the stars”, backed by a low-key ensemble of steady drum and dank keyboard. There is again the sense of the religious turning to the worldly: “The priest is passing round the dish, / Our Lady’s selling tissues for the tears”. There’s also history, with haunting references to Erwin Rommel and “hidden cities in Brazil”. While the song gains momentum when synthetic string sounds enter, it isn’t quite as great as it would have been with Patrick Q. Wright’s violin. Still, it is strangely affecting stuff, and ends aptly with the sampling of a creeping old 78rpm recording of ‘Ave Maria‘.

Next is the stupendous ‘The Grain Kings’, which from its title and its assiduous, dark opening conjures images of imperialist capitalism. This is Joseph Conrad pop, with purposeful, swelling synths and Neils’ saxophone accompanying a tale of worldly cultivation: “We shall feed the fertile ground. We shall wait and we shall gather foods to feed our hunger”. Production line percussion punctuates; the phrase “tidy lawns” stands out. The band had ditched the drum machine and Ka-Spel recalls that they’d “take turns banging and thrashing anything within reach”. The buzzing fuzz guitar dazzles, ensuring the track conjures up the polemical heft of Pink Floyd’s ‘Not Now John‘, as well as the spacey adventurism of the best Hawkwind material. ‘The Ocean Cried Blue Murder’ revisits some of the maritime madness of ‘The Neon Mariners‘, in piano ballad mode: “Penguin spins the caviar”, “We wash it down with absinthe”, “Captain turns the hoses on the crawling crowd”. It seems to me a dreamlike evocation of military adventurism gone awry and dissolute – bringing to mind Tony Richardson’s anti-heritage British war film, The Charge of the Light Brigade, which was in cinemas in April 1968 when Ka-Spel was 14.

‘Bella Donna’ maintains the steady, sedate pace, with grave organ and nimble guitar chord progressions. It has much of the weird whimsy and deft tunefulness of EKS’s fellow child of the 1960s Robyn Hitchcock, whose equally lengthy masterwork Eye had been released the previous year. This has a strength and life-affirming beauty paradoxical to the deadly titular plant: “pretty name for a flame”, “I’ll remember our dawn”, “starburst shouts from the grave”. It is serene psychedelia and seems very much of its time in its hopeful summoning of 1960s ghosts: Dream Warriors and A Tribe Called Quest were bringing new life to old samples, REM and James were providing ethically engaged anthems for the moral but irreligious: ‘Losing My Religion’, ‘Sit Down’.

Next, ‘A Space Between’ ups the tempo and ante. We are presenting with the varied grotesqueries of 17th century Blighty and JG Ballard, intermingled: “Billy was a car-crash – all he ever knew was pain”, “Red Harry was a bright young spark that flew and burned old London Town, in ’66. He tore it down (bubonic bliss!)” This captures something of the crazed nihilism of the film Psychomania (1972) with its marauding gang of undead bikers, running amok in mundane New Town supermarkets. “We / They all have names” is a great LPD refrain, one of those that repeats again and again, assailing the depersonalisation of modern life. It is a surreal, tall tale: “Georgie was a cut on Hitler’s knee […] On winter nights, I hear him scream”, Jane’s mother was a hurricane that sneezed away a continent, “the team made a myth by hiding it / Became a hit on Broadway. But it wasn’t quite the same / They all forgot our names”. This is a strange, melancholy epic about the transitory nature of culture: that ascends to ever more powerful heights with the late entry of The Silverman’s fuzzy guitar, which blazingly bestrides like the track like the Outer Hebrides over the British mainland. Tremendous stuff.

Side B

Side B opens with ‘Evolution’, which is another corker. This is a long improvisatory track, born of the process they used for TMD: it was recorded on an eight-track recorder in a barn on saxophonist Neils’ farm on the Dutch-German border, with “a stirring view of the [river] Waal”. They began with “long form initial improvisations” which they would then convert into shorter songs. This track has a beguiling long instrumental opening; followed by EKS’s words, which extend the “let’s do the Sixties again but even better” mood: the Fred Neil–Tim Buckley-citing “Maybe, in the next life, we’d be dolphins. WE’D BE DOLPHINS” and the direct profundity of “If we shared, instead of just collecting”. There is that fuzz guitar hitting the sweetest spots again, uniting with whirligig, kaleidoscopic synths to create dense, exploratory meshes of sound. This is so much richer and livelier sonically than TCVA.

‘Cheraderama’ is where things slip a bit; it’s a slow, patient tune with declaratives like “I mourn the death of colour” and “seeing the patterns on the wall”. It is more ponderous than what we’ve been used to, however many dark undertones. However, ‘Lilith’ marks a recovery; it is more Badalamenti than Goth, despite the gloomy images: “She hugged the sand, she cursed the storm, for 16 days and no tomorrows”. The synths are distant, forlorn and inscrutable; it’s like some of the outstanding incidental music Badalamenti composed for the extraordinary episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return, but is from the time of the original series’ transmission. It’s a beautiful, disconsolate, beyond-life sort of ambient music. It really doesn’t need the obvious final line: “She’ll always be alone”.

‘The Fourth Secret’ deploys Venus in Furs style fevered strings, backing ominous, massed chanting. It’s another stylistic detour within this kaleidoscope of a record, if not quite as winning as most of what we’ve heard previously. Next is ‘Expresso Noir’, which is, rarely for this album, a fairly tedious 220 seconds. Then, we have ‘Home’, which provides sedate, serene notes in a beguiling pattern. It sounds lavish, lush and, frankly, yellow, in synesthetic terms. It’s a return to the album’s topper standards following ‘Expresso Noir’.

The closing ‘Crushed Velvet’ juxtaposes several religions, but affirms that this is the domain of several Marias, who are more important and awesome: “through your eyes I heard a mountain laugh” and “through your senses I kissed dying time”. The music again sounds improvisatory and hazy, though from 2:35 it takes on a burlier sound with the entrance of clattering percussion; next, Neils’ saxophone enters to expand the song’s jazz-like feel. Then, we have the megalithic visions of EKS: “So it goes, we stand alone, by standing stones and turn them into circles”. In archetypal LPD style, this repeats to the end. This is a remarkably consistent record, on the whole, though 74 minutes is a bit of a stretch and the second half doesn’t quite match the first. It’s especially remarkable for gorgeous, searing use of guitars, a million miles away from Guns ‘N’ Roses; as Ka-Spel said at the time of Axl Rose’s racist and anti-gay lyrics: “I hate fascism of any kind, and I think they’ve been responsible for some pretty bad shit that way.”

This album takes its place in my list of favourite 1991 albums and is one of my preferred releases so far, ten years into the LPD story.

Spiritual Context

Adam: I recently suffered a horrible, previously unimaginable tragedy, which I am only now beginning to process. In the wake of this I have been thinking about my own spirituality and what being a Unitarian means to me.

I had what might be called a confused religious upbringing. My father is like a less plummy and nicer Richard Dawkins in his unflappable atheism; while, as a child, my Irish Catholic aunt would douse me secretively with holy water to ward off his malign influence. At my CoE primary school, I found some hymns, like the almost paganistic Harvest Festival-celebrating ‘I Will Bring to You’, with its lyrics “paper pictures, bits of string, I’ll bring you almost anything … the rainbow colours in the sky, the misty moon that caught my eye”, stirred deep earthy, reverential feelings in me; while other hymns, like Sydney Carter’s chastising ‘When I Needed a Neighbour’, pulled me down into terrible paroxysms of guilt.

While I went through a phase of obsessive prayer before bed, I also developed more idiosyncratic, personal rituals that seemed to hold obscure, spiritual import. I would lie on the bathroom floor next to the bath, towels covering both my body and my face, with the shower running, and just listen to the sound of the water in the darkness. I would stare at the lightbulb in my room and then press my hands against my closed eyelids, pushing down upon my eyeballs, believing that I could telepathically communicate with the splotches of colour produced upon my retinas.

Today, if you asked me whether I believed in God, I would likely answer along similar lines to Xavier: Renegade Angel – “I believe that we are here implies, to some degree, that there are forces larger than us” – which seems to bring me worryingly close to the incel-inspiring nouveau-shamanism/chauvinism of Jordan Peterson. In the past I have sometimes also answered that I believe “being beings“, which doesn’t seem to satisfy anyone, not least myself!

Meanwhile, my own pastor, without doubting his faith, often seems to have become a minister as part of a complicated post-modern intellectual exercise, taking great pleasure on ending his sermons with the most unlikely or gnomic expressions of religious devotion – “God bless beer” or “God bless… the crow“.

The Maria Dimension itself has a similarly ambivalent relationship to spirituality. The album’s lyrics stage a dialectic between freedom and oppression; enlightenment and superstition; unveiling and obscurity, which is never wholly resolved. Broadly speaking, the Dots seem to come down on the side of freethinkers, espousing personal spirituality while criticising institutional religion. Certainly, the album – with its disparate styles and Ka-Spel’s talk of multiple Marias – tends towards the pluralistic, rather than dogmatic.

Side A

Side A begins with ‘Disturbance’, which carries with it, as it slithers into view, some strange, heady resonances – its central melody as springy and reverberant as if played upon an electric wobble board. If it were a field recording, the song would derive from the same jungle swamplands as ‘Green Gang’ of the preceding year and album, capturing the atmospheric charge of the “hot oppressive nights” mentioned in the older track’s lyrics. Like ‘Green Gang’, ‘Disturbance’ has an insinuating, vaporous quality, as though the music were coiling in through one’s openings like smoke from a hookah. Ka-Spel’s lyrics are sung from the voice of the collective: “We’re the invisible invaders of your privacy, your dreams. We’re the spectres on your screen.” It is unclear whether this is self-mythologising on behalf of the Dots, as when the Prophet Ka-Spel used to begin shows by warning the audience: “We are not here to serve you … We do not jump through hoops for you.” Or else, whether this is the voice of state surveillance that sees all, as in ‘Echo Police’ from Asylum (1985)? Or could these words resonate from a vaster metaphysical plane beyond linear time? The voice that proclaims: “Maybe you’re just a number but We know your name and We’ll remember… ’til the end of time” in ‘Jewel in the Crown’ on Island of Jewels (1986) – the voice of the Angels of Judgement with Flaming Swords or the Great Patriarch God Himself – Saturn, King of the Planets and of Time. As the lyrics end around the half-way mark, the music rises to meet them, Bob Pistoor’s electric guitar and Niels van Hoorn’s elegiac horns swirling round one another in a crescendo of exultant intoxication.

From such heady heights, ‘Pennies for Heaven’ brings things back to earth with a bump, drawing us down from the realm of metaphysics to the level of cold hard cash. Constantly in The Maria Dimension there is this push and pull between the spiritual plane and the worldly; the sacred and the profane. Often, in the Dots’ view, it is the very agents of religion who hypocritically demand their dues and indulgences, like Robert Mitchum’s preacher after the gold in Night of the Hunter (1955); Matthew Lewis’ Ambrosio of The Monk (1796) corrupted by the temptations of the flesh; or the human, all too human brothers of Jason Devlin’s sublimely disturbing text game Vespers (2005), who succumb to the plague precisely because they close the gates of their convent against the stricken village, more concerned with saving their own skins than saving their souls.

Musically, a rather lovely finger-picked ballad a la ‘I Love You in your Tragic Beauty’ is joined by some haunting (keyboard) church organ until any delicacy is overwhelming by the rather terrifying pomp and circumstance of the chorus with its aggressively tinny synth, horns and militaristic drumming.

‘Pennies’ strains against its own allegorical rhetoric like the words of a depraved preacher’s sermon strain against their own venality. Jack Schaap, the predator pastor from the First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, is more like a figure one would encounter within the Residents’ discography than the Dots’, but his infamous ‘polishing the shaft’ sermon – “God I see a beautiful wife… I never dreamed of her… She’s very, very polished… Keep polishin’, keep polishin’…” – hovering queasily between the pull of the spirit and the pull of base desires, offers a real-life parallel of the hypocrisy when I believe ‘Pennies for Heaven’ seeks to disclose. A “silver bird” is thrown into contrast against “plastic spoons”; souls “ascend… to oblivion”; the high-falutin’ rhetoric of barriers of smoke and ascension and camels passing through the eye of needles becomes little more than a call for filthy lucre.

Sending the lyrics of The Maria Dimension to my own minister, he caught rather more than the “needle’s eye” line in ‘Pennies for Heaven’, noting that the concept of Heaven’s roads being paved with gold is common imagery found in Revelation 21:21: “The streets of the city were made of pure gold, clear as crystal.” This may be pure allegory, but for people living lives of desperation and deprivation, an image of Heaven as a kind of celestial Emerald city has utterly understandable appeal. While I earlier bit my thumb at Jordan Peterson, I do have sympathy for the view that humans need structuring myths and stories to give meaning to their lives. ‘Pennies’ asks us to lend a jaundiced eye to the motivation behind these stories.

Next comes the intensely stirring, elegiac, but satirically bitter ‘The Third Secret’, one of my absolute favourite tracks from this period or any period of the Dots. I’ve been really struggling to adequately describe the synthesizer sound here but… to me… it is almost as though the sound has a half-life and is decaying. Maybe Chez Dots is equipped with a radioactive synthesizer – I don’t know! The music borders on the dismal, yet also has a strikingly beautiful quality, aided by how world-weary Edward sounds. The lyrics are enunciated so clearly you want to sing along, but you always have to go just that little bit slower than you think since the vocals are just ever-so-slightly syncopated. This imbues the listening experience with a touch of hypnagogic jerking, that sensation of sudden falling one sometimes gets on the edge of sleep. The lyrics are similarly queasy, disclosing the patriarchal horrors at the root of much religion, but with a sense of sadness counter-balanced against the rage. You get the impression that Edward (and Phil?) truly believe in the human potential of spiritual feeling, but are resigned to seeing it warped and exploited in the name of power, blindly followed by zealots and crusaders and conquistadors and hoary patriarchs and the crowds that huddle about witch burnings and other ceremonial abuses. Yet, in spite – or because – of all this, faith persists.

It’s a triumph of a song, capped by van Hoorn’s wistful horns and a heart-breaking extract from ‘Ave Maria’. I will never tire of attempting to play it on acoustic guitar.

‘The Grain Kings’ took a while to click with me. It’s thuddingly industrial at first, with spacey synths drowned out by van Hoorn’s (intentionally!) discordant bleating. It’s not quite as difficult a listen as Velvet Apocalypse‘s ‘The Pleasure Palace’ or Island of Jewels‘ ‘Rattlesnake Arena’, but it has a disturbing atonal quality which jars against the more conventional (though no less brilliant) tracks that have preceded it. The track resolves itself into a thrumming quasi-mystical dirge with curious bleating interludes and lyrics about sowing seeds and gathering fruits. We seem to have travelled back further than Christianity to a point at which religion is inextricably intertwined with the cosmic cyclical rhythms of nature.

At first what sounds like a linear trek through an arid landscape becomes increasingly cyclonic as the second half of the track becomes a rich psychedelic instrumental with remarkable Pink Floydian jamming on guitar by Pistoor/Father Pastorius… not so much the slick, stadium-anesthetized Floyd of A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987) or even Dark Side (1973), but the wilder freak-outs of A Saucerful of Secrets (1968) or Meddle (1971). Some of those tracks, like ‘Echoes’, can induce ASMR shivers up my spine, whereas ‘Grain Kings’ has previously made the centre of my forehead above the bridge of my nose – the location of the ajna chakra or “third eye” – throb. Since I otherwise only experience this after prolonged periods of meditation, I am confident in proclaiming that the Dots have produced a transcendent piece of music with the last 4 minutes of this track! A heady feat!

‘The Ocean Cried Blue Murder’ is a languid ditty on keys and guitar, providing a small island of respite amongst the ocean of spiritual turbulence of the preceding 20 minutes and much of the 50-odd minutes to come. As noted by Tom it wouldn’t sound out of place on Any Day Now (1988). While the lyrics faintly suggest the eldritch horrors of H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1936), the overall effect is actually rather lovely. Likewise, is ‘Belladonna’, but here the effect is almost too lovely, like the Turkish delight given to Edmund in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), the BBC adaptation of which had been screened just a couple of years prior to the album’s release. There’s almost something sickly (and sticky) in the song’s gentle wash of silvery-pink tweeness. Musically this is quite a conventional guitar ballad, with strummed verses and finger-picked chorus. Niels van Hoorn’s horns add to the lugubrious air. It’s a gorgeous interlude, which borders upon the slight.

The last track of Side A, ‘A Space Between’ is another cracked cosmic triumph with some of the strangest, most baffling lyrics Ka-Spel has ever offered. Tom has already recounted some of these, interpreting them as relating to “the transitory nature of culture”. Tom’s reflection reminds me of the legendary late psychonaut Terence McKenna‘s quote:

Culture is not your friend. Culture is for other peoples’ convenience and the convenience of various institutions, churches, companies, tax collection schemes […] culture is a perversion. It fetishizes objects. It creates consumer mania. It preaches endless forms of false happiness, endless forms of false understanding in the form of squirrelly religions and silly cults. It invites people to diminish themselves and dehumanize themselves by behaving like machines.

Could then the “ghost in the machine” voice of ‘Disturbance’ be McKenna’s self-transforming machine elves of hyperspace – that playful alien consciousness that McKenna used to claim lay dormant within the so-called “spirit molecule” of DMT??? A friend who is a McKenna devotee once related to me a story of how, in a chemically altered state, he entered his bathroom, only to find that all the objects therein – cabinet; shaver; toilet; sink; shower head; medicine bottles; toothbrushes etc. – in union announced their presence in the room in a high vibrato voice: “We’re here“. We need not speculate that Ka-Spel and co. were themselves in a state of intoxication when they wrote The Maria Dimension to consider that the affective phenomena of ‘A Space Between’, from the spark that caused the Great Fire of London, to the hurricane that inspires a hit Broadway play, to the cut on Hitler’s knee, are all, like McKenna’s machine elves, expressions of the Logos, Gaia, the collective unconscious, universal animism etc.

Could then the “ghost in the machine” voice of ‘Disturbance’ be McKenna’s self-transforming machine elves of hyperspace – that playful alien consciousness that McKenna used to claim lay dormant within the so-called “spirit molecule” of DMT??? A friend who is a McKenna devotee once related to me a story of how, in a chemically altered state, he entered his bathroom, only to find that all the objects therein – cabinet; shaver; toilet; sink; shower head; medicine bottles; toothbrushes etc. – in union announced their presence in the room in a high vibrato voice: “We’re here“. We need not speculate that Ka-Spel and co. were themselves in a state of intoxication when they wrote The Maria Dimension to consider that the affective phenomena of ‘A Space Between’, from the spark that caused the Great Fire of London, to the hurricane that inspires a hit Broadway play, to the cut on Hitler’s knee, are all, like McKenna’s machine elves, expressions of the Logos, Gaia, the collective unconscious, universal animism etc.

For those of you who find such theorization far too woolly, perhaps consider the idea in terms of Bruno Latour‘s actor-network theory, that to understand any historical or sociological phenomenon we must attempt to consider the multiplicity of actants which are inextricably intertwined with that phenomenon. Was it a cut on Hitler’s knee that caused, on some micro level, Germany to lose the Battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943 and thus the war? Without that specific spark on Sunday 2nd September 1966 would the Great Fire of London still have happened? Without my ever having introduced myself to Matt online would I be sat here now writing this review? ‘A Space Between’ posits that not only does Matt have a name, “We all have names” – every spark, scar and actant; all things bright and beautiful; all creatures great and small.

Side B

Even though, from the above, it might seem that Gaia would be the primordial deity best associated with ‘A Space Between’, the morbid nature of the song’s lyrics as well as its sheer strangeness compelled me to link it to Pluto/Hades. This speaks to the provisional, somewhat improvisatory nature of my attempt to establish a pharma-cosmological system by linking each song from The Maria Dimension variously to a chemical-altering substance, a colour, an alchemical element and a celestial body/ deity:

| Song | Drug/Herb | Colour | Element | Celestial body/ Deity |

| Disturbance | Wormwood | Black | Lead | Saturn/Cronus |

| Pennies for Heaven | Erythroxylon coca | Metallic Sunburst | Gold | The Sun/Helios |

| Third Secret | Anabolic-androgenic steroids | Slate Gray | Fire | Hephaestus/Adranus |

| The Grain Kings | Cannabis | Midnight Green | Earth | Ceres/Demeter |

| The Ocean Cried Blue Murder | Synthetic cathinones | Ultramarine | Water | Neptune/Poseidon |

| Belladonna | Atropa belladonna | Silver Pink | Silver | The Moon/Selene |

| A Space Between | Dextromethorphan | Television Static | Sulphur | Pluto/Hades |

| Evolution | Ayahuasca | Psychedelic Purple | Mercury | Mercury/Hermes |

| Cheraderama | Salvia divinorum | Fool’s Gold | Bismuth | Planet X/Dolos |

| Lilith | Diamorphine | Ghost White | Arsenic | Juno/Hera |

| Fourth Secret | Psilocybin | Atomic Tangerine | Air | Uranus/Prometheus |

| Expresso Noir | Coffea Arabica | Burnt Umber | Iron | Mars/Ares |

| Home | Ecstasy | Cyber Yellow | Copper | Venus/Aphrodite |

| Crushed Velvet | Mescaline | The Colour Out of Space | Platinum | Jupiter/Zeus |

So, I have linked the first track of Side B – ‘Evolution’ – to ayahuasca, the entheogenic brew used by indigenous peoples of the Amazon basin in shamanic ritual. This is because the lyrics of this wistful, wishful song are like a prayer or incantation for a better vision of humanity in which humans share and forgive and live as part of nature instead of trying to conquer it, finishing with the cry: “Maybe in the next life we’d be dolphins!” Where Tom is reminded of Fred Neil and Tim Buckley, I am reminded of Douglas Adams and these lines from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979):

For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.

Of course, there have people before Ka-Spel and Adams more enamoured of dolphins than of humans. In the early 1960s Dr. John C. Lilly attempted to foster communication being humans and dolphins, creature he believed man had a great deal to learn from. Many of Lilly’s experiences involved ingesting LSD either in a sensory deprivation tank or in the company of dolphins. ‘Evolution’ strikes me as ideal music to listen to in a sensory deprivation tank – far better than the generic relaxation panpipe music you see on CD stands in garden centres and new age shops. It has a hint of Brian Eno‘s start-up music for Windows ’95 about it. One wonders what it would be like being a dolphin on LSD listening to it!

Tom doesn’t seem to think ‘Cheraderama’ is much cop, but I really like it – principally, I think, because it reminds me of fantasy adventure game music from the early 1990s, such as the soundtracks to Adventuresoft’s Simon the Sorcerer (1993), Sierra’s King’s Quest VI (1992) and Revolution Software’s Lure of the Temptress (1992). It has a slightly generic fantastical MIDI sound that triggers my nostalgia gland. The central melody walks a fine line between beautiful and rink-a-dink and the movement into the chorus is a little too tonally jarring but, unlike Tom, I find the declaratory lyrics rather evocative and Edward delivers them with earnestness and gusto. There’s also a gorgeous tinkly keyboard bit at 03:40 to 03:50! Overall however it does feel a little out of place; theatrical where the rest of the album is cosmic. It would perhaps have been a better fit on Crushed Velvet Apocalypse, perhaps between ‘New Tomorrow’ and ‘Princess Coldheart’.

‘Lilith’ is a ghost of a song, that seems to take place at a time “when the evening is spread out against the sky/ like a patient etherized upon a table” (T.S. Eliot, J. Alfred Prufrock, 2-3). If one is not engaged it can slip past you into the background, but if you pay it attention it will haunt you. It reminds me of Ka-Spel’s later solo material like Ghost Logik 1 (2012) and 2 (2014), though not stretched out to such long, immersive lengths. ‘The Fourth Secret’ is another ambient work, but more tremulous and restless, surging and deep. The chanted lyrics are not reproduced in the album’s booklet and so might be assumed to be nonsensical. It is however a song that seems to promise the allure of meaning; perhaps the most mysterious on the whole album. It sounds as though it could be very effectively played upon a gamelan orchestra. It is one of the more percussive tracks here and reminiscent of parts of the Residents’ The Ughs! (2009), reviewed by Matt along with accompanying album The Voice of Midnight (2007) back in 2013.

‘Expresso Noir’ seems to deal with far more quotidian concerns that the rest of The Maria Dimension – the agonies of an uncomfortable train ride. It is certainly much better than the poem I once wrote while enduring such a journey, but like an expresso shot, is over rather quickly without having quenched your thirst. I do however like how the lyrics use enjambment to rhythmically reflect the stifling claustrophobia of the journey, much as how the metre of Auden’s poem ‘The Night Train’ famously captures its subject’s chugging rhythm.

Getting onto this colossal album’s home stretch, ‘Home’ is a delectable piece of ambient psych-folk, left unadorned of drums or vocals. It builds slowly yet inexorably, as beautiful a piece as one by Ulrich Schnauss. Really stellar and decidedly yellow (a feeling arrived at wholly independently from Tom) this is some of Phil Knight’s finest work. ‘Crushed Velvet’ is even more remarkable – a micro monument of thrumming psychedelia in self-aware Beatles ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ mode: “Through your ears I heard the mountain laugh, the banshee cry, the statue of Mohammed roll a dice to plastic Buddah, screaming ‘Christ! Another six! I guess it’s time to pack my things and head back slowly to Nirvana.'” What begins like a blissed-out prayer evolves to a swirling maelstrom of over-layered harmonies and sounds, dense enough that Hans Meyer must have contributed some of his electronic devices to it. As a cataclysmic climax of a stellar album it reminds me of the wonderful ‘The Whole World Window‘ at the end of Cardiacs‘ great 1988 album A Little Man and a House and the Whole World Window. I only wish that it were longer!

Adamendum

The first 3000 copies of the European CD edition of The Maria Dimension included a bonus 3″ CD. The first track, ‘I Dream of Jeannie’, we already covered in our review of Traumstadt 1 (1988). Along with the other four tracks, ‘IDoJ’ resurfaces on 1995’s Chemical Playschool 8 & 9 compilation so – considering the already substantial length of this review – we will discuss it, and them, when we get there.

However – briefly – The Maria Sessions Volume 1 and Volume 2 (2012) are worth considering. Both offer snapshots of the long improvisatory jam sessions from which The Maria Dimension was born. Both offer moments of rapture amongst stretches of inertia, but are essential listening for any fan of the album, providing you with an idea of the band’s working methods and songcraft at this juncture of their career. The music fluctuates compellingly between the ecstatic and the sinister and provides particularly sterling examples of the late Pistoor’s guitar playing.

Though it is hard to pick out individual songs, I especially like the last tracks of both. ‘Part 4’ of The Maria Sessions begins as the kind of evil carnival music that I’m a complete sucker for, moves into an exceedingly brief snippet of Eastern-sounding guitar, then becomes a wailing ambient wash in a bath of static! ‘The Right Setting’ is the longest track on Volume 2 and, unlike the rest of the volume which was recorded in a tiny club in Oslo, hails from de Hoorn’s barn in Klaverland. I must only assume the barn was haunted by the ghosts of farm animals for such spooky music to have emerged.