While this review of Asylum Relapse (2018) is not officially part of the Legendary Pink Dots Project, Patrick Wright has been such an instrumental part of some of the band’s greatest albums, such as The Tower (1984), The Lovers (1984), Island of Jewels (1986), Any Day Now (1988) and, of course, Asylum (1985), we have categorised it there for posterity. Sing while you may.

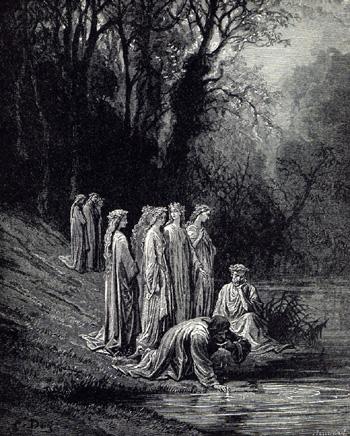

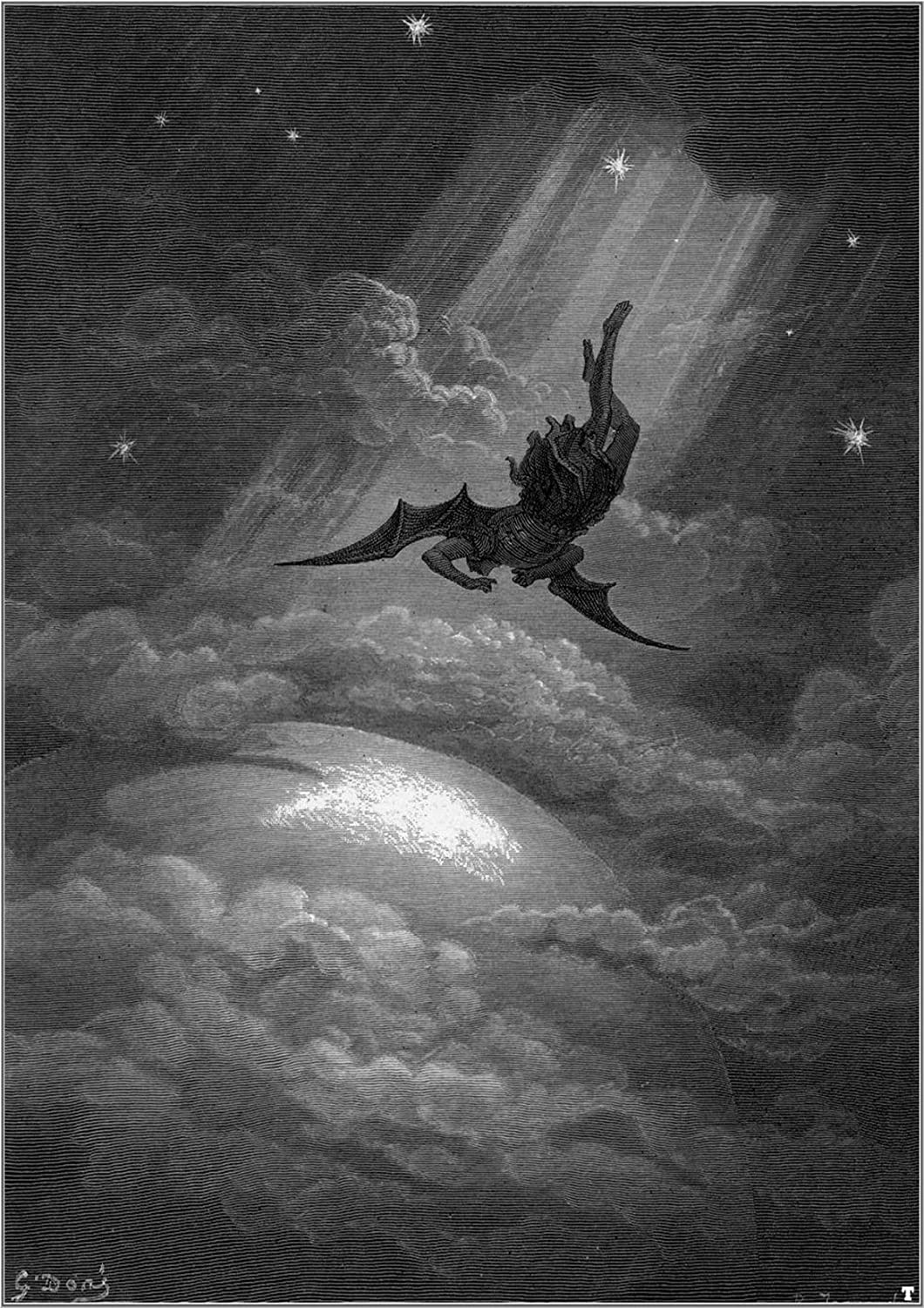

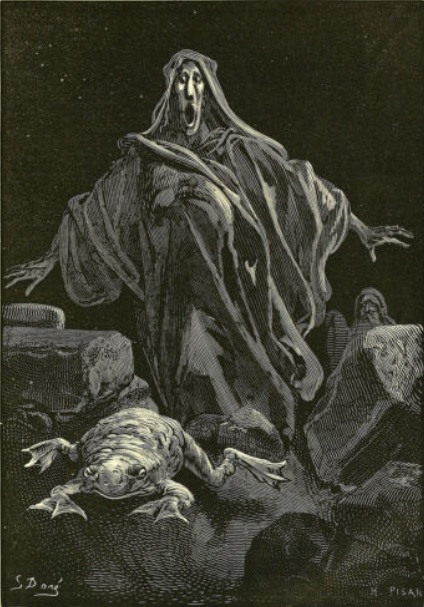

Tom: This was recorded in PQW’s home Raintree Studios in Umbria, Italy; the ample CD booklet includes beautiful, haunting artworks by Gustave Doré (1832-1883). He was a French artist and cartoonist who had illustrated literary works by Tennyson, Dickens, Milton, Cervantes, Coleridge and, even more relevantly for the LPD lifeworld, Rudolph Erich Raspe’s satirical book Baron Munchhausen’s Narrative of His Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia (1785). Doré was known for his piercing documentarian eye for London’s social evils in Dickens’s day, which illumines what PQW attempts here. In the same booklet, Wright recalls how a disturbing urban incident influenced the Dots’ recording of their album Asylum (1985). Wright notes the violent threat from a close friend’s boyfriend who was beating her up. He left a football scarf on Wright’s doorstep and “He’d told all his mates I was dead meat”.

1: ‘Blind Date in Purgatory’

Presents a gothic folk song underscored by Simone Copellini on flugelhorn. There is especially soaring, regretful PQW violin near the end, emphasising “One girl full of love” whose brother dies of illness and who ends up dragged away by “the inquisitor”.

2: ‘Lion’s Mouth’

Edward Ka-Spel sings here and presumably writes lyrics. “Sleeping like a baby” instead of “lion” as it reads in the booklet. It seems to be from the perspective of a subjugated servant giving a baleful portrait of “the master” who needs taking by “six” to rehab for his drinking habit. This becomes a rich, doubting reflection as to whether he should keep standing quiet and passive or actively resist, it seems resolved in its irresolution: “While this pattern of existence is now written in the stars / I’ve come to feel resistance will. Not get me very far”. Wright’s chirping violin expresses this malodorous, looped uncertainty in its persistent refrain to the close.

3: ‘Till Death Us Do Part’

There are early 1980s synth sounds and Wright’s vocal tones now resemble the David Sylvian of Brilliant Trees (1984) or Gone to Earth (1986) vintage. Giorgia Fanelli enters to sing of violence, anger, to be joined by Wright to denote hate. Such things could speak of events in Washington, DC on 6 January, but here is the microcosm: a relationship that has become destructive. The opposite of love. The musical timbre is stately despair.

4: ‘Hill of Stone’

Wright tells another story of might is not right. A “fragile” woman “beguiled” by a man who makes her a victim. This song has nifty, insistent and urgent guitar strumming from Giulio Angori which is unlike much I have heard in the LPD oeuvre from 1981 to 1995.

The song feels vaguely reminiscent to me of something like the great producer and avant-pop star Thomas Dolby’s ‘I Scare Myself’, but catapulted into a different dimension at the climax by Wright’s fiery, tortured violin.

5: ‘Paradise Lost’ (including ‘Demonism’ and ‘Cinder Moon’)

Slow violin with mandolin and Angori’s trumpet and flugelhorn enter in this instrumental. It builds into a momentary Hollywood-Gaelic major key crescendo before subsiding. There is a playful jaunty violin which becomes distended and treated with effects. Which descends down into a gloomier slumber. Around the 200 second mark, a thudding, steady beat enters and the piece opens out into a grave, languid Gothic canter. This fades into a wispy beat-less section closer to modern classical before Wright’s lower violin tones are heard in isolation. The end section feels eerie, harried and builds into ominous filmic crescendo but Lynch knows what sort of cinema it would accompany… The booklet has words but we don’t hear them, they infer potential ecstasy but which is cruelly snatched by anger and regret. The woman ends up fleeing him.

6: ‘Daynight in Paris’

Piano and violin open in delicate dialogue, with Wright exquisitely plaintive. We hear murmured voices and a sensitive saxophone. “Leave behind unanswered prayer / Journey in this castle in the air”. This feels closer to the serious discursive intensity of This Heat, Camberwell Now or Bark Psychosis in the massed, double tracked vocals, which is fine by me! There is an evocative Doré painting behind the lyrics in the booklet, with faded violets, greens and yellows above and below a black sea. A ship with elaborates masts is in the sky, falling, in front of an illuminated moon and bustling clouds. This is a haunted lonely odd to doomed, quixotic individual endeavour, and my favourite so far.

7: ‘Finding Heart’

This continues with the grave, post rock register of ‘DiP’. I must admit I don’t like it quite so much as it detours into more boisterous rock around the 80 second mark, however this does bluntly underline Wright’s lyrical assault on crass values. He directly assails capitalistic greed and governments’ darkly absurd foreign policy ventures. “Make love not war” comes the righteous, grave rejoinder. “If might is really all that’s right and money the only thing that talks […] then all we’ll ever do is fight…” Wise words, Patrick. As much in 2018 when this was recorded, or in 2021 as in the 1960s.

8: ‘Four Worlds’

This seems a curiously New Wave satirical dig at iPads and emojis. Like Andy Partridge of XTC in its sardonic askance sneer. There’s a tremendous section of screeching violin around the 3 minute mark. I don’t quite take to Wright’s William Blake-quoting anti-technological attack on consumerism, however much I may agree with it!

9: ‘Still Burying Michael’

For me this works a lot more. It seems less diffuse, more focused in its target, fewer puns, more channelled anger. Advancing on the Dots’ ‘The Hill’ from Asylum, Wright clearly communicates anger at the Trumpian idea that was circulating in the US of arming teachers. This has a grim sense of the absurdity, danger and needlessness of gun ownership.

In the booklet, Patrick mentions his strange premonition when on tour of a gun school shooting and how the Hungerford massacre occurred and led to the 1988 Firearms Act “which restricted the use of shotguns and bans ownership of semi-automatic weapons”. Having been 13 when the Dunblane school massacre occurred in March 1996, I am proud that we British have legislated to restrict and monitor gun ownership. It is a task that urgently needs undertaking in many countries. Wright contributes a forceful, eloquent protest song all the better for its barbed absurdism:

“Teacher’s got a gun / You know it makes so much sense / Teacher’s got a gun / They can shoot at anyone…”

10: ‘The Scream’

Mournful, sedate strings join a slowly bouncing didgeridoo type sound. Edward Ka-Spel sings in the guise of a controlling would be puppet-master. “Do not contradict me! Look directly at the lights!” as Wright’s violin gets more frenzied. “In-vaccinated, sterilised!”

Amanda Palmer enters, seemingly in medias res: “And I dreamed of lentil soup…” And speaks from the perspective of someone used and controlled against their will. There is a paranoia: “Did you steal my number? / If I don’t have a number / I can’t have a star”. The outro is low-key, mournful folk sounding.

11: ‘Requiem’

Wright’s key line here is “living has no law”. This is a wise cautioning against living for legacies or being overly focused on what your epitaph might be. It is a tentatively optimistic note to end the album. However, Wright doesn’t airbrush pain – “living has no cure”. Yet the “light of day” day beckons and he implores: “Let me fly to where I want to be / Let me fly to where I can feel free”, which bears melancholy relevance in this era of Covid-enforced spatial confinement.

I like this album; while inevitably, perhaps, it isn’t as consistent as From Here You’ll Watch the World Go By, it is a substantive, darkly opulent sequel to the Dots’ Asylum. And ‘Daynight in Paris’, ‘Finding Heart’, ‘Still Burying Michael’ and ‘Requiem’ gleam brighter now.

Adam: There is a mental health epidemic at the moment. Confined to our homes for a year while loved ones get sick and die, many of us have retreated inwards, our brains seizing upon past guilt and trauma as the devil makes work for our idle furloughed hands. Attempted to escape the neocolonial indignities of Brexit, my partner and I attempted to flee Britain for the Dots’ home country of the Netherlands (much as Edward did upon Thatcher’s third reelection) only to find ourselves in lockdown in a barely furnished apartment in a country where sentiments towards the British were running very, very cold. While now back in our old home (on our own street in our old town) stripped of our rights as European citizens, but among friends (albeit not ones we can see in person) my mental health is still fragile at best.

Patrick Wright’s newish album Asylum Relapse has provided – if not exactly respite in these difficult times – a sympathetic sounding board that resonates with my intermittent feelings of isolation and estrangement.

The sound is more reminiscent of symphonic metal than most Dots material, especially the folksier passages in albums by the likes of Opeth and Nightwish. These tend to be my favourite parts of such albums and Wright is imbued with enough irreverence and whimsy that he manages to avoid those band’s po-faced excesses. My partner felt that first track ‘Blind Date in Purgatory’ evoked the acid burn-out grooves of Ozric Tentacles and the piratical rhythms of Flogging Molly.

Sometimes the expansiveness of the music guards against intimacy. Wright’s lyrics tend more towards the socio-political and personal than the cosmic – there’s nothing like Arjen Anthony Lucassen’s century-spanning Ayreon saga or the convoluted song suites of Dream Theatre – which keeps the album grounded. Sometimes, as in ‘The Lion’s Mouth’, this poses a minor problem since the chamber story of a servant stewing with resentments over his master’s Bacchanalian lifestyle doesn’t quite justify the sweeping strings and whirling feedback. The song feels a little unfinished, as though – with lyrics and vocals contributed by Ka-Spel – it could be a LPD also-ran.

Indeed, I much prefer hearing Patrick’s softer, less sardonic voice here, even when, as on ‘Till Death Do Us Part’ the lyrics strongly recall LPD tracks about relationships falling apart as on The Lovers, and the acoustic-industrial soundscapes of later Dots albums like Your Children Placate Your From Premature Graves (2006) and The Gethsemane Option (2013). I especially like his singing on the album’s fourth track ‘Hill of Stone’, which is where the album really hits its stride for me. Samuele Martinelli’s guitar is shifting and elusive, conspiratorial. The other instruments are given space to play, even while Wright’s violin remains centre-stage. The quiet-loud dynamics recall flamenco-touched bands like The Scaramanga Six (another comparison from my partner), sharing the torturers from Yorkshire’s indebtedness to English murder ballads. The lyrics here, however, are more emotionally sedate, seemingly narrated by an asylum inmate caught up in the shadows of her own mind. Lyrically the album shifts from melancholy (as here) to mordant criticism (as with ‘Still Burying Michael’).

‘Paradise Lost’ quotes from ‘Demonism’, one of the most obscure tracks from Asylum. Wright’s seasick violin rises and falls like an arched eyebrow. Simone Copellini’s flugelhorn recalls the famous melody of Ravel’s ‘Boléro’. What was an off-kilter chamber piece with weird harmonics is transformed into a stirring mini-epic that wouldn’t be out of place on Tuomas Holopainen’s Music Inspired by the Life and Times of Scrooge (2014). I can imagine the track scoring a mafia movie set in the Lake District – perhaps one of the imaginary films referred to in the titles of Wright’s 2017 release Unfinished Sympathy: Music for Unmade Films.

‘Daynight in Paris’ is, note-for-note, my favourite track on the album. It is a delicate and plaintive fairytale of a song, bordering upon a dirge. Patrick’s keyboard playing is utterly lovely, recalling – once again – the Dots album The Lovers. I’m also reminded quite of lot of William D. Drake, which makes sense since, like Wright, he’s a former member of a band (Cardiacs) who contributed rather more to the sound of their early albums than some fans seem to realise. It’s the timbre of the sounds that really captivate here, which are wet and tactile. Indeed, some of the noises are even animal-like. Antonia compared the track to Anathema, who I know for a stonking cover of Pink Floyd’s ‘Learning to Fly’.

The lyrics to ‘Finding Heat’ are a bit too on-the-nose for my tastes. I’m really not keen on the opening lines: “When the whore of war / Has sucked you dry / You walk away, zip up your flies / You watch as a flower slowly dies”. To be fair, it is hard to write an anti-war song that isn’t platitudinous; though exceptions do exist, such as Pete Seeger’s ‘What Did You Learn in School Today’ or even ‘Shahla’s Missing Page’ from Amanda Palmer’s and Edward Ka-Spel’s I Can Spin a Rainbow, upon which Wright also worked.

The next track, ‘Four Worlds’, is very Amanda Palmerish with its whispered vocal lines, Brechtian staccato piano, and whirl-a-gig rhythms. It has a pleasingly obnoxious electric violin solo with Wright playing the violin much like Snakefinger played his guitar for The Residents. Tom wasn’t keen on the lyrics to this one, but since my hatred of much of the internet (and abandonment of social media) has only grown during lockdown, I found its sly and silly commentary on the evils of digital alienation very pleasing. The lyrics to ‘Still Burying Michael’ are similarly satirical, but rather more serious in intent. Michael, from Asylum’s ‘The Hill’, is back, but this time the teacher is armed too.

Where the Dots’ original song was carnivalesque, Wright’s updated take is positively funereal. Production-wise it’s probably the strongest on the album, with a real sonic sense of expansiveness and weight. The original song was very much Wright’s song and the maestro does it justice here. There’s also a fat bass-line at the end! I can’t decide if the track is deliberately citing Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)’ or not. I hope it is!

‘The Scream’ sounds the most like a track left off I Can Spin a Rainbow, which makes sense since Palmer and Ka-Spel both sing on it. It has that album’s gothic iciness. Edward sounds like Syd Barrett doing an impression of Pops from the 2000s BBC comedy The League of Gentlemen! Amanda offers an emotion-strained and haunted vocal line… and then the song just sort of peters out. The track feels like it could have been fleshed out further, but that might just be the prog nerd in me speaking. It is very atmospheric, I just wish it soared more.

The final track, ‘Requiem (Epitaph)’ is a lovely piece of faux-Celtic folk with a gorgeous counter-point vocal melody. It is a plaintive ending note for an album that exists confidently upon its own terms separate to the Dots, even while it revists themes – the trauma of war; school shootings; mental illness; alienation – from Asylum.

—

The physical CD comes with Patrick’s behind the scenes documentary of the American leg of the I Can Spin a Rainbow tour. It is an enthusiastically inventive piece of low-fi amateur filmmaking that will appeal to fans of Amanda Palmer in particular. I found it a little rough-and-ready but entertaining. It gives you some insight into the rehearsal process and you get to see the fabulous ranch that Palmer shares with her husband Neil Gaiman. It reminded me of days long past of reading her insightful and oft dramatic Livejournal posts. For good and for ill Palmer has always been a queen of canny self-mythologisation, which intersects interestingly and awkwardly with her commitment to personal authenticity. I have fond memories of a particular diary entry in which she wrote about being holed up in a hotel room on a Dresden Dolls tour, watching Alan Parker’s 1982 film of Pink Floyd’s The Wall on repeat. That must have been back in 2006 when I was young. We are all old now.