Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!—

Tom: I am sitting, typing this, in perhaps the same classroom I sat in at lunchtime on Friday 24th June 2016, articulating my thoughts about The Tower (1984) in the light of the 3.8%-margin Brexit vote. Most people have gone home – quite right, as it is 5:30pm! I am listening again to Island of Jewels, and Donald Trump has been president-elect for a month.

‘Tower 6’, an apt return to that former dystopian album, is a brilliant opening: it emerges amid distant, subdued echoes of battle. Then we have a plangent, evocative guitar: the first one distant, the second stridently centre stage. Strangely, one is brought to mind of Hendrix’s ‘Star Spangled Banner’ performance at Woodstock in 1969, if not in exact sound, but in its underlying mood. This is a meditative, delicate fanfare to lead us into the strange depths of this album.

Next: the remarkable ‘The Red and the Black’ – its anarchism implying title suggests a political thrust continued from ‘So Gallantly Screaming’. It opens, matter-of-factly: “Reflecting on the Empire after eight… pig’s head on a plate white wine… The mint imperials circulated…” It is a brilliantly punning, incisive broadside against the worst of Old England and Old Europe and the nostalgists who would bring such “glories” back: “Captain sips his brandy, curses Ghandi, dreams Napoleon and Delhi turns to jelly; Bombay ducks; Calcutta shivers down in its hole… Old England is out to rule the waves again – banging on the table! Routing the reds and the browns and the yellows.”

This is a vision of the unconcealed racism we see in those laughable-turned-terrifying jingoistic fools, Trump and Farage.

There’s a curious jazz undertow, Robert Wyatt-ish, to it; in its geo-political engagement, this really isn’t so far from his Old Rottenhat (1985) and Dondestan (1991) albums. It is all very Second Cold War, with the influence of a Gorbachev not apparent:

“My union’s name is Jack, and it’s a ripper! hammers her head with a sickle, nails monkey to the tree […] And Moscow is charred.”

Then, suddenly, we have evocatively dated, 1986 synth sounds that were all over British television at the time; for example, the soundtrack to Howard Brenton’s Dead Head, a very unusual BBC conspiracy drama from the same year.

‘The Dairy’ is a bit Momus, apt as this was the year of Nick Currie’s brilliant first album, Circus Maximus. Yet this is closer to 2000s-era Momus than the acoustic Brel tendencies of that album; here is a jaunty, odd mix of eastern European, ‘Oriental’ and vaudevillian stylings. There are references to the mythical American “cowboy” archetype. When I think of “Donald Jaaaaayyy Trump”, this is a persona that has gone beyond even the Reagan or Dubya swaggering “cowboy” into a deranged, braggadocio-powered businessman id: Jordan Belfort gone wrong-er.

‘Emblem Parade’ is all violin-led elegance cantering into murkier waters. The Eastern European fatalism of The Lovers (1984) seems back again; though Old Man Stalin wasn’t – to paraphrase Scott Walker. Mikhail Gorbachev had been elected Soviet President in March 1985, though he would indeed have to face plenty of unreconstructed ‘party loyalists’ in the Communist Party ranks. Gorbachev’s attempts at a reformed, socialised communism would ultimately come to nought against a mix of nationalist and ultra-free market forces.

‘Jewel on an Island’ is a horror film. A human one, which might suggest, for Britons in 2016 thoughts of Ken Loach’s current film I, Daniel Blake, with its heart-wrenching depiction of the human cost of an utterly absurd, labyrinthine, Kafkaesque welfare system, created by New Labour and extended remorselessly by uber-tosser Iain Duncan “IDS” Smith. There are never-more-relevant-than-now references to “borders”. Also, there is imagery of violence, suffering and imprisonment. “Her Tower. MY TOWER.” This ending conveys the sort of humanism that seems in shorter supply now than in 1986: that lovely year of deregulation and Thatcher’s ‘Big Bang’ freeing of the City of London. The year also of The The’s Infected, with its visions of the UK as a 51st state of the USA.

The following ‘Rattlesnake Arena’ startles and uncoils, aptly enough, like a sinister serpent. A star-spangled, intense lead electric guitar heralds a 1980s psychedelic merry-go-round. A strange chorus emerges, singalong as anything: “Rattlesnake Arena, burning red black, red black, Rattlesnake Arena burning red black, RED BLACK!” Red and black are, of course, the colours of anarchism. There’s a mockery of “glory, glory, hallelujah!” with pitch-shifting amid weird editing. There’s typical Ka-Spel wordplay – “Gutter snipers” – that makes you ponder why no-one had thought of such a phrase before! This is one among many imposing highlights of an album which enthrallingly extends the LPD reach and scope.

‘The Shock of Contact’ returns to Astrid who we have heard about on The Tower. This is another LPD song about revolutionary, terrorist acts, with the resultant deprivation of all material comforts. It’s a bitter, pretty cheerless song, of candles shared in cellars: “Making bombs / I planted them in galleries / Your salary it was wasted / Oh, how criminal…” As delivered by Ka-Spel, the declarative adverbial “I touch you there” is far from suggestive of pleasure…

‘Jewel in the Crown’ adopts the title of Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, which had been adapted as a lavish Granada TV drama production in 1984. The negative “No soul” is repeated, denoting further alienation. It displays a curious brew of different 1980s musical aesthetics and it maybe isn’t quite as weirdly beguiling as Leicester-born Daryl Runswick’s theme to another adaptation, the BBC’s My Family and Other Animals – which you can listen to here! This forgotten 1987 TV theme is one of those things I might have heard in my childhood: beauteous, strange, gliding and ethereal. Like a piece of Les Baxter exotica but hazier and refashioned for the 1980s, ascending on a becalmed stairway to the thermosphere. It is ‘Forever and Ever’ but instrumental and stranger, no Roussos in residence. Jonny Trunk should play it on his Resonance FM OST Show, if he hasn’t already… Runswick’s theme is the sort of 1980s music that electronic maestros like Massachusetts’ own Daniel Lopatin has himself sampled and refashioned as Oneohtrix Point Never… Lopatin is almost exactly two months older than I am, and ‘Jewel in the Crown’ is tantalisingly close to the easy-turned-uneasy listening nostalgia that our generation seems preoccupied by. The 1980s was an age where TV themes and adverts still seemed imbued with connotations of ‘exotica’ – or, maybe, my assertion arises from the fact of these sounds being my most formative experiences of music, before I really ‘knew’ what music ‘was’.

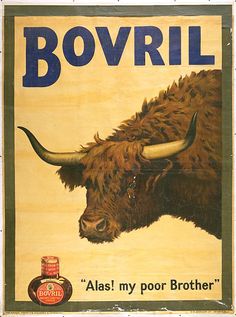

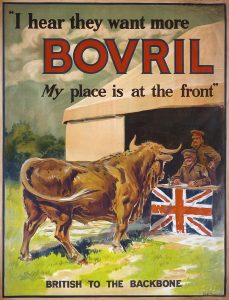

‘Our Lady in Chambers’ has grave, ritualistic piano that seems in keeping with the titular allusions to Catholicism. Contrarily to the religious connotations, this is one of those LPD songs with grounded, earthly reference-points: ‘Tom and Jerry’ drinking that disgusting beef-extract ‘drink’ Bovril and football – in the sense of the famous WW1 ‘Christmas Truce’ match between British and German troops in no-man’s land. I have posited ‘grounded’, but then there is the utterly bizarre image of ‘Swines in schnitzels’…! And there’s one of the oddest, most garish and frankly tasteless puns in all of the LPD oeuvre so far – “Zyklon tea”. The grotesquery is enhanced by several very Residents-like crescendos (I find it amusing that what Tom hears as Residents-like, I hear as James Bond music! -Adam), which suggest the condensed absurdity and atonal circuses of Duck Stab / Buster and Glen (1978).

‘Our Lady in Khaki’ is a slow, stripped-down, guitar-led rumination. There is further war imagery and use of the collective pronoun “Our boys”. Our Lady is said to be selling poppies to Our Boys, evoking The Tower’s ‘Poppy Day’ with its focus on historical false-memories. The Odeon could evoke either Ancient Greek arena where poets competed for prizes or the modern-day cinema exhibiting films. I worked in the latter, indeed a branded ‘Odeon’ in Newcastle upon Tyne from 2005-6, before getting a job as a college lecturer.

“Cracking jokes about THE JERRY!” references WW1 propaganda and its powerful influence on subsequent British generations’ xenophobic attitudes. This shifts into ‘Our Lady in Darkness’, a tremendous curio of a tune that is initially languidness incarnate, with weird metaphors followed by a bleak Beckettian focus on time: “she’s an hour glass – but time has died.” It then detours markedly into Viv Stanshall / Bonzo Dog Band territory, with Rawlinson End-like contrarily grave and sprightly piano. There are hints of Slapp Happy, some 1980s style slap bass and even Michael Nyman or Steve Reich style beautiful repetitions.

‘The Guardians of Eden’ is a rueful, can-we-rebuild-it scenario; the calm after the tyrant’s destructive reign. There are absurdist and seemingly heartfelt invocations of religious lexis – “We’ll turn the weeds to wine” and “we’ll see our kingdom come”. There is a profound sense that all is transitory; not just the good things, but the bad. Can love be the longer term legacy, even when it seems hate is in the ascendancy?

Island of Jewels is a record with the darkest omens but also holds out a surprising kernel of hope. It is one of the most transformative, outwards-facing Legendary Pink Dots records yet.

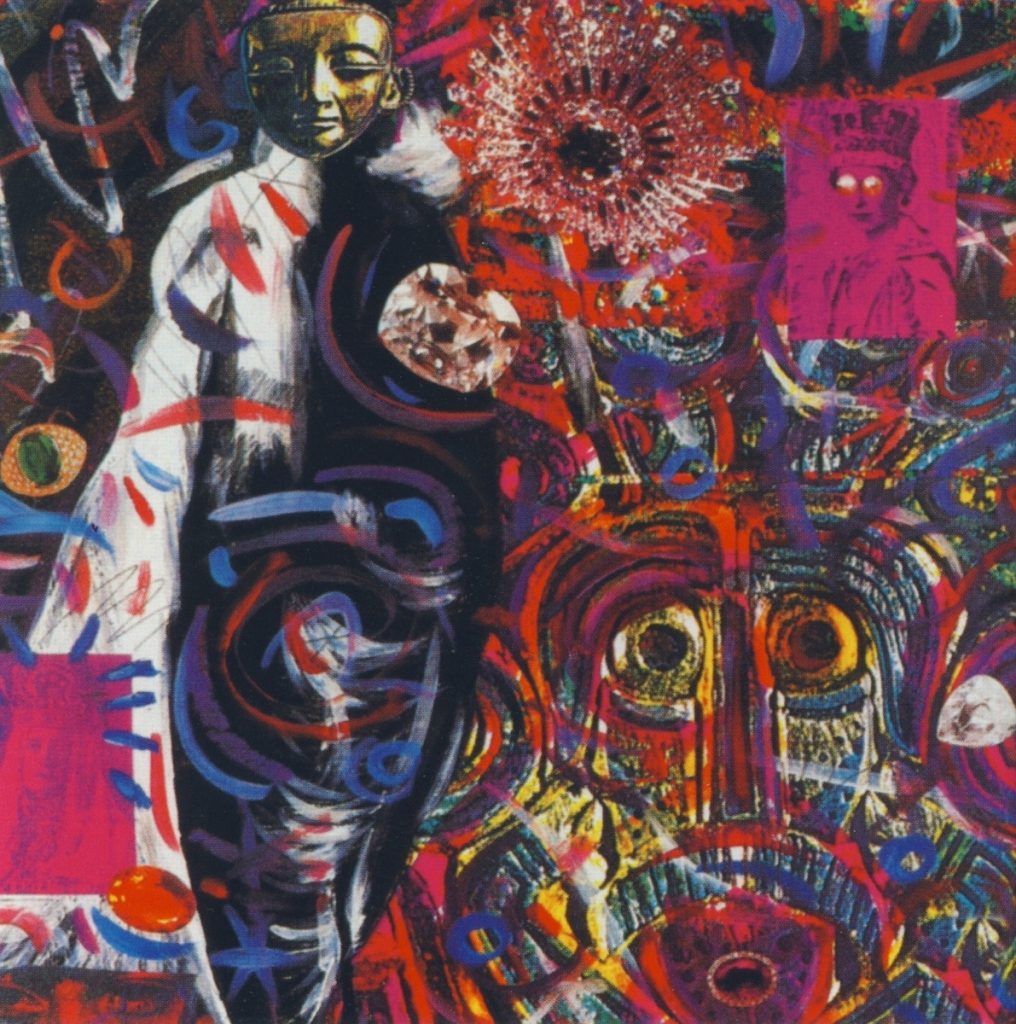

Adam: Island of Jewels is an album of moth-eaten vestments and emptied out symbolism. It is densely allegorical, but strangely gutted as though you approach it post-dissection after it has already been opened up and disemboweled. I am left feeling spent every time I venture into its auditory arena. Somewhat bizarrely the album is known as one of the most palatable of the band’s mid-80s releases. Admittedly this would be true if one were only asked to digest its music, which is served up in meaty, only marginally off-coloured chunks, in comparison to Asylum‘s scattered and rather fragrant rinds, crusts and bits of gristle. However, IoJ is a supremely literary album and while its lyrics don’t work without the accompanying music*, it would be likewise impossible to understand the thematics of the album without attending very closely to Ka-Spel’s vocals, which seem especially enunciated and high-in-the-mix to ensure the listener’s focus. This is in sharp contrast to Prayer for Aradia of the preceding year, where Edward’s vocals were often indistinctly buried under fuzzy layers of sound. Here, instead, there are even characters you can follow! The Captain:- a moustachioed colonial relic like Blackadder‘s General Melchet performed by a bloated and palsied corpse. Our Lady:- Queen Elizabeth II at a fancy dress party in a cheap Queen Victoria costume. Astrid:- a long-suffering martyr to violent, revolutionary struggle, reincarnated again and again only to be exploited in the name of The Cause. These characters appear in the songs like figures in some Hellish diorama, staging enervated, post-colonial pathos before a backdrop of ludicrous and absurd theatrics, illuminated by cold neon lights with cardboard props grotty and water-damaged and costumes which are splitting at the seams.

The album begins with ‘Tower 6’ bridging IoJ to its thematic predecessor. ‘Tower 6’ is like the middle ‘time passes’ section of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse (1927), a bottleneck of time connecting two separate epochs that we might picture in our minds as a cinematic montage of clocks ticking, buildings falling, people dying.

Night, however, succeeds to night. The winter holds a pack of them in store and deals them equally, evenly, with indefatigable fingers. They lengthen; they darken. Some of them hold aloft clear planets, plates of brightness. The autumn trees, ravaged as they are, take on the flash of tattered flags kindling in the gloom of cool cathedral caves where gold letters on marble pages describe death in battle and how bones bleach and burn far away in Indian sands.

Violins scrape. Tumult rumbles somewhere far away – in some distant country or locked away in the attic. Fingerstyle acoustic guitar picks out a looping pattern with the kind of plaintive melody the late Greg Lake would use to punctuate the song cycles of Emerson, Lake and Palmer. An electric guitar whines out ominously. The overall effect is to create a kind of earth-bound space rock that never quite manages to get into orbit. The tone created is one of uneasy melancholy. An ascending keyboard motif strikes a fragile note of hope, snuffed out by the scrotum-tightening opening of ‘The Red and The Black’, which begins with a statement of purpose: “Reflecting on the Empire after eight”.

LPD are a literary band and the title of the track might refer to Stendhal’s 1830 novel of the same name. The novel takes satiric aim at the hypocritical and self-serving machinations of the aristocracy, the military, and the Church, by turns. If the song’s title is a reference then it acts to position Ka-Spel and his lyrics within the same satiric tradition.

‘The Red and The Black’ is divided approximately into two sections. The first section, which lasts until 02:13 is a disquieting cacophony of burbling saxophone, jazz piano and lardy, undulating bass. (Can something be both buoyant and languorous? Somehow the bass here manages it.) I’m not actually sure if the song is in free time, or if the amusing resemblance to The Magnetic Fields’ daft ‘Love Is Like Jazz‘ just makes me think that it is.

The lyrics stage puns as sites of libidinal repression. For example, “My union’s name is Jack and it’s a ripper” reads as a cheerily nostalgic expression, the kind one might find in a 19th century Boy’s Own magazine i.e. “I live in Britain under the Union Jack – it’s a ripping good country!” but simultaneously evokes the violence that underpins colonial nostalgia via image of “Jack the Ripper” i.e. white men secured their Victorian colonial stranglehold upon the world stage through the kind of violence exemplified by Jack the Ripper. If this seems like a stretch, one might consider Alan Moore’s From Hell (1989-1996) which treats Jack the Ripper as a ghoulish embodiment of the patriarchal violence that simmered under the placid surface of Victorian Britain. The society which covered up their table legs in a bid to avoid corrupting the virtue of young girls (okay, they didn’t really, but it’s a telling myth) was simultaneously rife with the horrors of child prostitution. Rather than this being a contradiction, Moore hints that conservatism and corruption actually live inside one another, twinned in a symbiotic and parasitic relationship.** The sugar in the dainty teacup is from a slave plantation. There are bloodstains on the table skirt.

Appropriately, the allegorical tableaux for the song’s first half is of the Captain sat at his dinner table. You can imagine him staging his battles with the pepperpots and the condiments. “Routing the reds and the browns and the yellows” – the ketchup, brown sauce and mustard are knocked down and defeated. “Bombay ducks” could mean that the city formerly known as Bombay (now Mumbai) cowers defensively, or else, the table is laden with spiced bummalo, the lizardfish delicacy local to the area. Likewise, the somewhat weaker wordplay of ‘Delhi turns to jelly’. Considering that British colonial rule in India (the British Raj) developed out of the rule of the British East India Company, who made enormous sums of money from foodstuffs such as sugar and tea, it makes considerable sense that the Captain might confuse Indian cities with the foodstuffs he has plundered from them.

Of course, not all the references feel so antiquated. To the British listener the line “Pig’s head on a plate” will invariably conjure up the “Piggate” scandal of 2015, in which then Prime Minister David Cameron with accused of sticking his penis into the mouth of the severed head of a dead pig as part of one of the grotesque rituals of the privileged inner circles of Eton college.

The first half of ‘The Red and the Black’ ends with a flurry of tape samples similar to those that intrude upon the soundscape of Asylum‘s ‘So Gallantly Screaming’. The music becomes more elegiac, almost sacrosanct and quietly anthemic. The drums have that 1980s fake hi-hat sound, which makes me miss Keith Thompson’s drums, although the electronic drums here aren’t entirely out-keeping with the tone of the track and have a nice timbre. A disturbing vocoder-encoded voice echoes Edward’s vocals as they are wrapped in blankets of synth. The lyrics momentarily shift from Captain to a Colonel Gaddafi-like figure, ‘counting the corpses in stadiums with his shades on’, a line which often produces a shudder in me… as does Edward’s lisp on “the bright light hurt his eyes”, which follows.

Suddenly we are back to Captain, who is sitting up screaming in bed. It was all just a bad post-colonial dream. The night nurse “wipes his forehead” clean and soothingly settles him back under the covers, whispering into his ear, “Try to sleep… back to sleep”. I picture the elderly and dementia-stricken general in Roy Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor (Sånger från andra våningen, 2000) laid in a metal cot, confusedly saluting a “Heil Hitler” to an embarrassed congress of former comrades and visiting dignitaries. In fact, Andersson’s work would make a good companion piece to IoJ, sharing as they do a mordant humour and both haunted by the ghosts of the two World Wars.

‘The Diary’ is one of those grotesque, pervy songs from this period – like ‘Love in a Plain Brown Envelope’ from ’84’s Faces in the Fire – animated by cold, mechanical desire and almost greasy to the ear. I’m sure many more examples can be found, but I can only remember Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage album (1979) sounding so obscenely engorged. The drums are loud and synthetic; the keyboards as fat as flies. The song is vaguely funky in a grubby and insinuating way. Ka-Spel screeches unpleasantly; the violins lurch. All-in-all, the song is relatively unpleasant to listen to and almost brings up a little bit of vomit into the mouth on stickily descriptive lines such as “Get them creaming at the dairy, pumping lonesome ‘cross the Praries” (or “pumping loathsome clots“, as I first heard it). We have moved from the relationship between pornography and its consumer as examined in ‘LiaPBE’ to the creamy heart of the porn industry itself with its libertarian-libertine dreams of freedom and conquest (all achieved while clad in only a rhinestone studded cowboy hat and assless chaps). I think I find the mix of the intoxicating music, with its insistent, almost industrial rhythms that pummel the listener into submission, and the ickily suggestive lyrics particularly nausea-inducing because the song implicitly links the humping and pumping of porn performers to the milking of cows and their perpetual forced insemination.

It is a dehumanising vision that sits uncomfortable against a 3rd wave feminist perception of porn that focuses upon sex positivity… however, it must be admitted that as a description of a certain mode of porn production it fits the career and character of self-styled cowboy of sleaze/ pornographer Max Hardcore to a tee and anticipates Jarvis Cocker’s dead-eyed 1998 track ‘This is Hardcore’ with its lyrics: “Oh that goes in there, then that goes in there, then that goes in there, then that goes in there and then it’s over.”

‘Emblem Parade’ is essentially a violin piece, strident and evocative of Shostakovitch, though not an advancement upon the template laid down by the opening and closing sections of Asylum‘s ‘The Last Straw’. Quite fun to stride down the street to though!

Like Tom, ‘Jewel on an Island’ immediately put me in mind of the deaths of benefits claimants under the currently Tory government (at least 2,380 people died between December 2011 and February 2014 shortly after being judged “fit for work” by the Department of Workfare and Pensions). Last year in 2015 the irritating, but politically incisive band Fat White Family released their track ‘Tinfoil Deathstar’, which explicitly referenced the death of David Clapson, an army veteran on benefits who died with no food in his stomach and lacking the money needed to keep his refrigerator plugged in, which kept the insulin needed for his diabetes working.

The Dots’ grim ballad of a financially destitute woman named Jenny instructing her young daughter on how to help her “mummy” commit suicide becomes as bleakly absurd as a play by Samuel Beckett as each suicide methods fails… There is no power for the toaster thrown into the bathtub; the razor cut across the wrists turns out to be a safety razor; plastic knives just snap. The existential horror of a person endlessly failing to commit suicide has been mined for laughs in media as disparate as Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day (1993) – when Phil Connors attempts suicide over and over only to find himself alive once again at the beginning of the day – and the poetry of Dorothy Parker: “Guns aren’t lawful; Nooses give; Gas smells awful; You might as well live.” The song plays out like a Hellish dirge (on keyboard) before a soundscape of chittering ghosts and howling synths until Patrick Wight’s violin kicks in, ushering through the door a rasping electric guitar and a brisk change in tempo. After some majestic violin playing it all ends where it began, but with Jenny trapped in prison – literal or metaphorical, it isn’t clear. What is clear is that Edward Ka-Spel sounds like a metallic demon when he hisses “Round and round we go. Her tower. MY TOWER!” in the track’s final lines. This might be another expression of the solipsistic understanding of relationships we see later on the album with ‘The Shock of Contact’, under which it is impossible to truly connect with another human being since we are fundamentally unable to escape the prison/s of our own ego/s.

(Of course, “MY TOWER!” might also have phallic significance a la Yeats’ The Tower (1928), flagging in angry impotence in the face of the confounding “labyrinth of another’s being”, choosing to stand proud and tall, rather than risking love. How this ties into the rest of ‘Jewel on an Island’, however, remains obscure.)

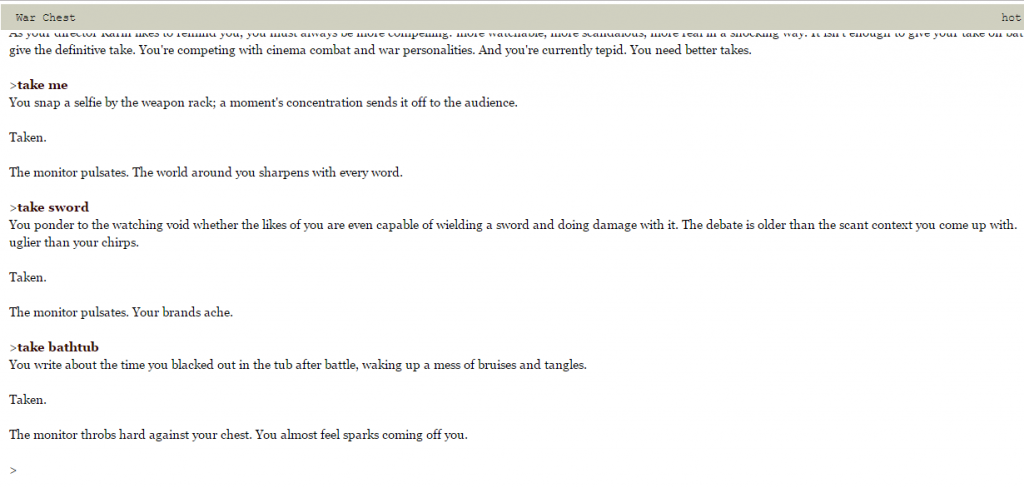

‘Rattlesnake Arena’ conjures up endless cycles of pain and degradation. It is an utterly relentless track. A synthesizer pulses with hideous urgency to the monotonous clang of metal upon metal. This forms the percussive beat of the track. The melody is provided by an electric guitar strangled into whining; a melody exactly matched by Ka-Spel’s contorted vocals. If Paul Glaser had wanted to make The Running Man (1987) a full on horror film he could have used ‘Rattlesnake Arena’ on the soundtrack. Arnie could have sung it. The song is ridiculously claustrophobic and even at a brief running time of 03:34 starts to give me a headache like my head and ears are being crushed inside a small metal box. It even features a noise which sounds like a chainsaw being revved up! Although playing a text-only adventure game while listening to ‘Rattlesnake Arena’ would be nigh-on impossible, its thematics make the track an evocative companion piece to one of my favourite games of the year – Katherine Morayati’s remarkable Take, a one-verb-only text game dystopia of hot takes, fameballs and heterosexual dating. Endless cycles of pain and degradation.

Next comes ‘The Shock of Contact’, which is one of my very favourite LPD songs, but which is so clear-eyed in its execution, that I don’t feel I can say so much about it without over-ladening its brilliance with words.

By the time the Dots get to IoJ Astrid has already been established as a character in several songs on 1984’s The Tower. In a ‘Lust For Power’ she is introduced as a co-conspirator (and possible lover) of the anarchist narrator. The entire song is addressed to Astrid and the listener is put in her position as the narrator tells us his fears that the telephone line is tapped; government agents spying through the curtains. The words contain an almost psychotic/conspiratorial edge of paranoia, but reading the lyrics in 2016 after the passing of the Investigatory Powers Act in which the British government passed into law the right to investigate the internet records of any British citizen, whether under suspicion of criminal activity or not, the narrator’s suspicions seem rather more reasonable. Less reasonable is his vaguely sado-masochistic glee as he informs Astrid: “We’re not alone. We can give them all a show when we make love!” Astrid’s own side of the story is voiced in the character’s heart-breaking eponymous song in which she laments her neglect by the narrator, reflecting upon all the letters she sent which were burnt; all the lies which her told; all the night spent alone. Finally, in ‘Tower Four’ she appears martyred as “Sister Astrid”, who now “never says a word” since her correction. The form in which she was corrected is never hinted at, leaving the listener to conjure up her own images of interrogations, tortures, sexual violence, or a tongue cut out.

Moving forward two years to Island of Jewels and we are given what seems to be an overview of the relationship between Astrid and her callous, revolutionary lover, told from the vantage point of the end of the relationship by the revolutionary, whose stream of constant explanations and self-recriminations stand chillingly in contrast to Astrid’s absolute silence. The word “mansplaining” didn’t exist back in 1986, but the phenomenon of socially woke, politically engaged guys talking over their neglected girlfriends certainly did. ‘The Shock of Contact’ feels especially relevant in a year in which misogyny in the Left has often been in the spotlight. Owen Smith, Jeremy Corbyn’s rival in the Labour leadership election back in September of this year, talked about wanted to smash Prime Minister Theresa May “back on her heels”. Left-wing activist Peter Tatchell and his supporters invaded the stage as Corbyn gave a speech on domestic violence against women in an attempt to derail the conversation onto Syria (hugely important, but so is femicide). Just three years back a leader of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) was accused on multiple counts of rape and the victims quizzed in a kangaroo court about their sexual histories. Last month Julian Assange faced a Swedish prosecutor in London over allegations of sexual assault.

In Ka-Spel’s lyrics the personal is inextricably intertwined with the political. The fact that ‘The Shock of Contact’ is delivered in both 2nd person and present tense increases the listener’s sense of intimacy and immediacy. The music is uncomplicated so as not to distract from the lyrics. The keyboard repeats a simple four note sequence with variations, with some light baroque tinkling in the background. The key changes in the chorus. And then we’re back to the verse, but this time with added violin and sonix. The effect is not unlike Portishead‘s majestic ‘The Rip’. Ka-Spel’s vocals are put high in the mix. Things slowly grow more diabolical so that when the chorus’ retrain of “The shock of contact keeps us warm” shifts to “The shock of contact keeps me warm” it feels like the perfect, inevitable climax to the whole sad and sordid tale. As the vamp out fades into silence Ka-Spel’s “you touch me there” has shifted invariably and chillingly to “I touch you there”.

In Ka-Spel’s lyrics the personal is inextricably intertwined with the political. The fact that ‘The Shock of Contact’ is delivered in both 2nd person and present tense increases the listener’s sense of intimacy and immediacy. The music is uncomplicated so as not to distract from the lyrics. The keyboard repeats a simple four note sequence with variations, with some light baroque tinkling in the background. The key changes in the chorus. And then we’re back to the verse, but this time with added violin and sonix. The effect is not unlike Portishead‘s majestic ‘The Rip’. Ka-Spel’s vocals are put high in the mix. Things slowly grow more diabolical so that when the chorus’ retrain of “The shock of contact keeps us warm” shifts to “The shock of contact keeps me warm” it feels like the perfect, inevitable climax to the whole sad and sordid tale. As the vamp out fades into silence Ka-Spel’s “you touch me there” has shifted invariably and chillingly to “I touch you there”.

Things don’t get any cheerier with ‘Jewel in the Crown’, a song about how militaristic governments sanction war crimes perpetrated by their country’s brave boys. This is another track which feels gallingly appropriate at the back end of 2016 here in Britain since the government’s announcement to pull Britain out of the European Convention of Human Rights, thus ensuring greater impunity for soldiers who would otherwise be brought to trial on human rights abuses. Instead of offering a sardonically detached perspective however, the Dots thrust us into the thick of things, with energetic, reverb-drenched funk guitar communicating the delirious intoxication of a soldier who has been told “amuse yourself; abuse at leisure”. Cosmic effects from the keyboards with plinky plonky sounds I associate with the mid-period output of The Cure (go to 02:03 and you’ll understand what I mean) ensure that ‘Jewel in the Crown’ is slightly less airless than many of the other, more claustrophobic tracks on the album. Patrick Wight’s violin is elegant and haunting. The rhythms are seductive and the melodies hummable. The tone is still characteristically grim-dark, but the listening experience is a surprisingly easy one.

Which makes it easy to miss the brilliance of the track’s final lines, which are worth quoting in full:

“Take your role in history. Maybe you’re just a number but WE know your name and WE’ll remember. Yes, WE’ll remember ’til the end of time.”

This is not the first time that Ka-Spel has taken on the voice of some kind of transcendent Other. Regular readers might recall that in Asylum‘s sinister but playful ‘A Message From Our Sponsor’ he roleplayed as an unctuously malevolent non-interventionalist God(!) Here, in ‘Jewel in the Crown’, he shifts from the singular to the collective. The collective subconscious maybe? Or else a being akin to Walter Benjamin’s magisterial ‘Angel of History’?

The point being made is, I think, that being remembered is a double-edged sword. Recently I finished reading Nick Turse’s essential yet harrowing Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam, which discloses the full scale of the hideous abuses committed by U.S. forces during the Vietnam War. Soldiers who shot farmers in their paddy fields; tortured and killed innocent civilians; abused, raped and murdered women and children – the vast, vast majority of these soldiers will never see their day in court; their victims forgotten and unnamed in the history books. And yet, the crimes occurred. They are frozen immutably in the amber of the past. And, perhaps somehow, the song suggests, Being itself bears witness. The double-edged sword of remembrance is that those you serve, your King and Country, may place a wreath upon your head and a rosy glow upon your actions, but if a different story can be told – a different mythology of a boy with “a horn, a sawn off shotgun and a cause” who screws and sweats under “a molten tower” of napalm – then that story may one day be remembered. In Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 documentary on the Indonesian genocide of “communist” Chinese farmers and villagers, The Act of Killing, one of the perpetrators reminds Oppenheimer – somewhat defensively; somewhat smugly – that history is written by the victors. ‘Jewel in the Crown’ darkly prophesizes that the victors’ grasp upon the official narrative of history might not be quite as total as they (and their cronies) might like to think.

The final third of the album comprises the “Our Lady” triptych of ‘Our Lady in Chambers’, Our Lady in Kharki’ and ‘Our Lady in Darkness’. These songs exemplify Ka-Spel’s description on the Dots’ official bandcamp of the album as “Medieval Industrial music”. ‘Our Lady in Chambers’ is an exquisite chamber tone poem in mordantly toe-tapping 4/4 time. Oddly, I didn’t notice quite how cracked the lyrics are until I read them. Because it all transpires at a nice walking & whistling pace and sounds convincingly sincere, I must have mouthed along to it, nodding profoundly with furrowed brow and melancholy smile, many tens of times before I clocked that “Tom and Jerry drink their Bovril, crawl out from the trenches swap their wives, and swap addresses til Our Lady’s calling time” is a bugshit weird way of evoking the fabled 1914 Christmas day armistice.

It’s a wonderfully surreal piece of workplay, but Heaven knows if it portends to anything! Either way, it’s a gorgeous piece of music interspersed with fiery spurts of James Bond-esque crescendos and has the most cracking drum machine loops in any Dots song thus far. It’s one of the tracks I would present to those who dismiss the Dots’ music as I think it’s a piece with clear melodic invention and rhythmic clout. It’s haunting and trippy without being meandering or pretentious… faults that might sometimes, not unfairly, be ascribed to both the Dots and my reviewing style.

‘Our Lady in Kharki’ confronts the the deceptively banal everydayness of a complex moral conundrum – the fact that money from the sale of red poppies goes to the British foreign legion. The phrase “Our price. Our choice. We bought one” reappears in ‘Pennies For Heaven’ on 1991’s The Maria Dimension as “Our price. Our choice. We rarely make the right one”. The finger-picked guitar melody also returns, although at a faster tempo and with slightly more complexity in the later song. ‘Our Lady in Kharki’ is sang like a nursery-rhyme incantation, giving it a hallowed, fable-like quality. Ka-Spel gives a whispery, restrained performance until his wrenching howl of “AND WAIT FOR GOD!” which concludes the track, catapulting the listener into ‘Our Lady in Darkness’, an eerie and gothic chamber piece, centered upon the image of “Our Lady … hanging headless, charred”, a baby sucking at her desiccated breast – her body an “hourglass” with its sand run out. It’s a image frozen mid-way between the morbid allegory of Holbein’s 16th century painting ‘The Ambassadors’ (1533) and Francis Bacon’s Hellish ‘Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ (1953).

The sheer viscerality of the image (with its faint misogyny) clashes with the fact that it is clearly working within a symbolic, non-literal mode i.e. Our Lady/ Margaret Thatcher as metonymic stand-in for the Island of Jewels/ Great Britain. There is violence as language shifts abruptly between the figurative and the literal. It’s not clear whether the anarchists of ‘The Shock of Contact’ whose vacillating fortunes we’ve been following since The Tower have finally found success, but we are told that “the blast was final”… and if things are especially dire for Our Lady, things aren’t looking much better for Captain, who we leave “flat down in the urinal”. The queerly charming instrumental that marks the end of the song, with its bass sounds that sound as though they are coming to our ears from underwater, is redolent of the Penguin Cafe Orchestra. I don’t generally have a synesthetic response to music, but somehow this instrumental passage perfectly evokes the purple, violet, gold and maroon of the album’s original cover.

Taken altogether, Rich Will accurately describes the ‘Our Lady’ triptych of ‘Our Lady in Chambers’, ‘Our Lady in Kharki’ and ‘Our Lady in Darkness’*** as “languid, dark” and “beautiful”.

Island of Jewels comes to an end with a melancholy and reflective coda similar to the closing track on The Tower, though with a bitter-sweet note of hope which ‘Tower Five’ lacked. ‘The Guardians of Eden’ describes seeds being scattered and weeds being turned to wine, the world made once again into a garden. It is a simple, pretty track for keyboard and guitar. The question is whether such a pre-lapsarian utopian is possible in spite of humanity’s existence, or only in our absence. With Trump’s ascension soon at hand at the start of 2017 the Guardians of Eden may discover the answer to this question all too soon.

* I discovered this while reading the lyrics booklet and finding that lines which I found disquieting when sung, seemed a little daft when read on the page – such is the importance of Ka-Spel’s delivery.

**Alan Moore and Edward Ka-Spel have many cross-over interests: the struggle between fascism and freedom; Kabbalic spiritualism; the inter-connections between the personal and political; patriarchal violence; female magic; madness and wisdom. Indeed, The Tower and Island of Jewels are not dissimilar to Moore’s contemporaneous V for Vendetta (1982-1988) in their imaginative reaction to Thatcherism.

*** A title which invariably makes me think of Mervyn Peake’s 1956 novella Boy in Darkness.