Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

Tryst 7 (1994)

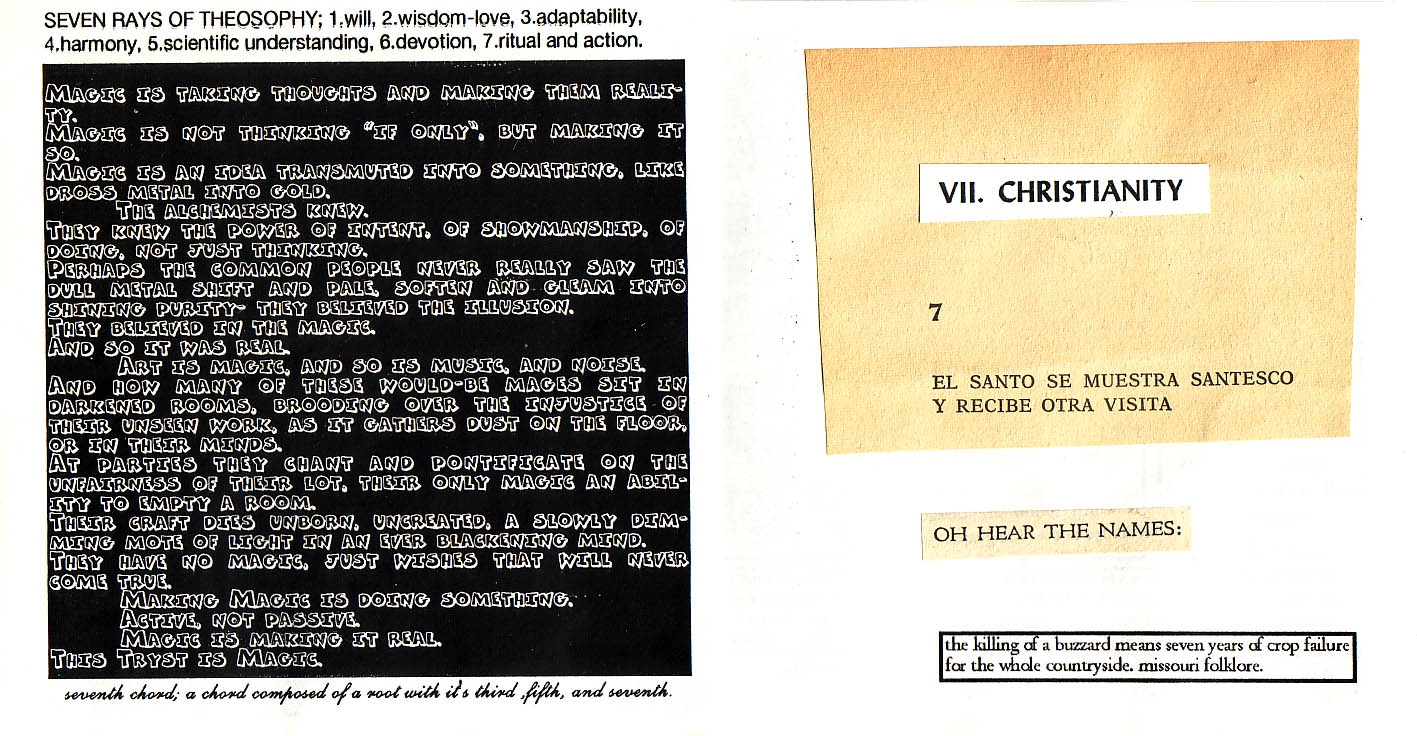

Adam: Tryst 7 is a relatively obscure split cassette release by the Dots and Big City Orchestra from 1994. The latter are a Californian anti-art collective of ever-rotating members who produce experimental noise collages of an absurdist and sinister bent. Album titles such as Bob Hope’s Fruit Loop Special (1986), Painfull Audio Enema (1989), A Child’s Garden of Noise (1994) and Dada Is Dead, Long Live Dada (2006) should provide some indication of their eclectic and occasionally off-putting style.

Fascinatingly and frustratingly, the cassette was released (even in its limited run of 200 copies) in four different forms. The Dots and BCO each provided two different mixes of their own material, with these mixes then paired in both alternate combinations. As such, I don’t even know if Tom and I are reviewing the same two half-an-hour tracks of music!

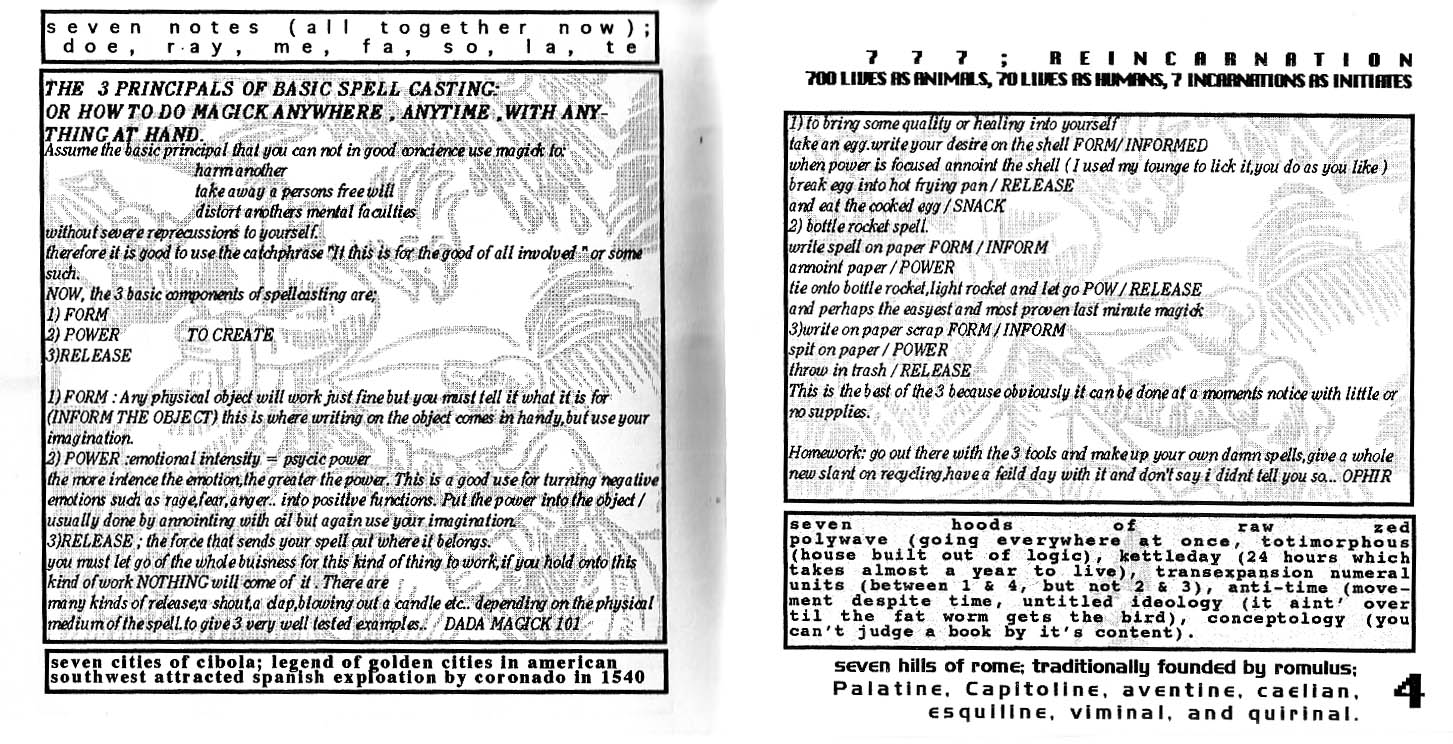

The BCO side of the tape that I’ve been listening to is a scrambled auditory invocation that flips willy-nilly between the sublime and the ridiculous. Legendary ethnobotanist and psychonaut Terence “DMT Machine Elves” McKenna acts as something of a shamanic guide for proceedings, coaxing us to close our eyes and “have a dream” while “listening to the magical tryst”. McKenna psychedelic-cum-Jungian philosophy (that might be boiled down to “culture is not your friend so take the deep dive!”) resonates nicely with Ka-Spel’s own… a kind of rigorously wry and sceptical mysticism.

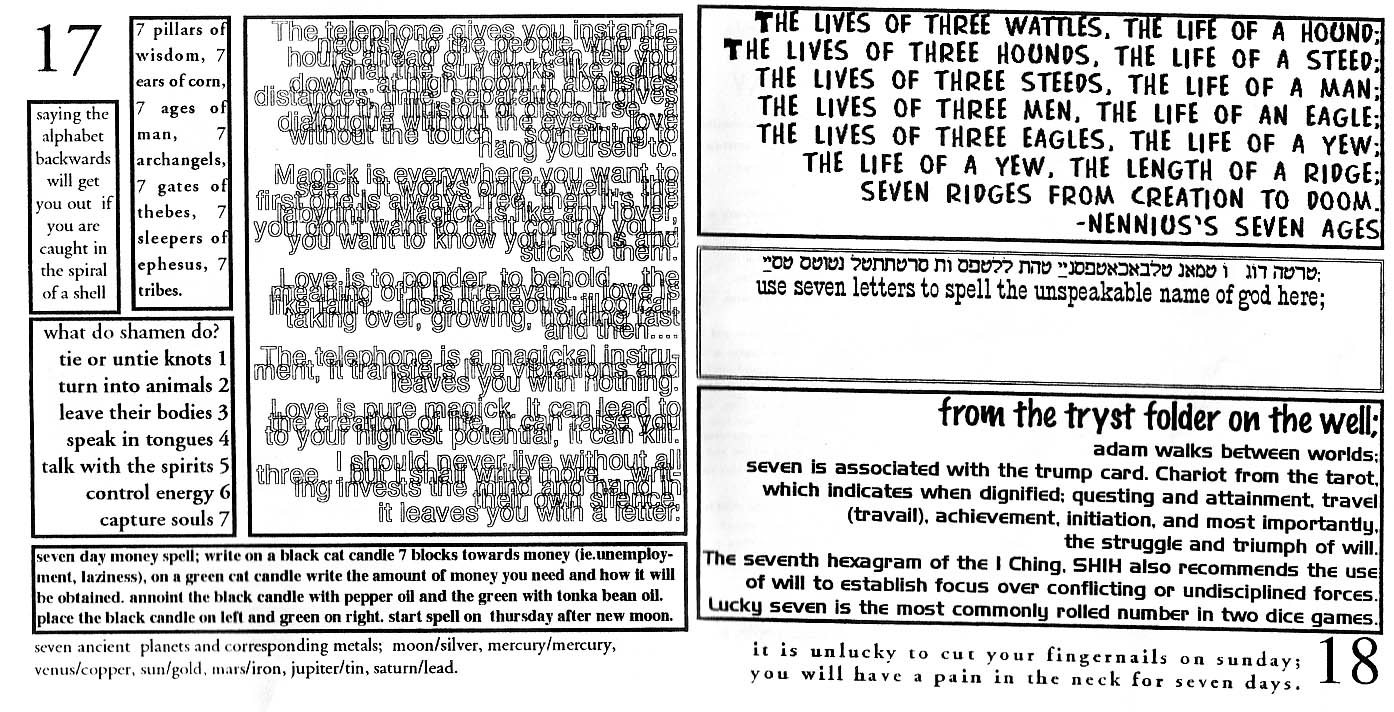

Over this discombobulating period of Coronavirus lock-down, I have re-watched David Lynch’s and Mark Frost’s mesmerising and maddening Twin Peaks: The Return for the first time since its release back in 2017. In this third season, which continues the seminal early ’90s show some 25 years later, the character of rogue psychiatrist Dr. Jacoby, who was based upon Terence McKenna, has forged a new identity as a kind of libertarian shock jock called Dr. Amp. Using alchemical imagery close to the Dots’ own, he urges listeners to buy a golden shoven to “shovel [themselves] out of the shit!” The Return is filled with allusions, mirrorings, associations and esoteric patterns to such a degree that it becomes very difficult to separate out the sublime from the ridiculous, to sift the gold from the shit. Eileen G. Mykkels has charted some of the numerology of The Return, in which the number 7 features predominantly:

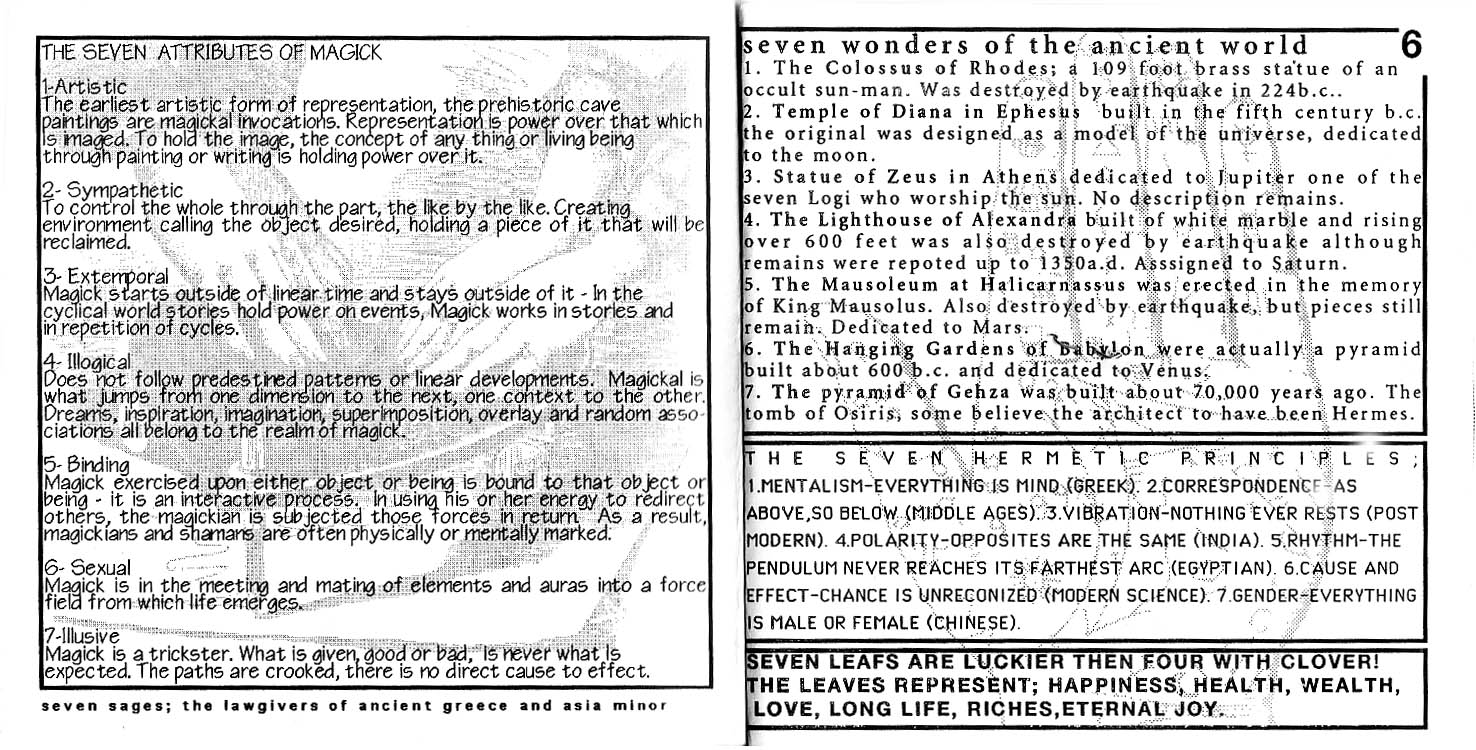

“The elevator through which Phillip Jeffries appears in Fire Walk With Me is elevator number seven. Dougie/Dale work at Lucky 7 Insurance. Dale wins the slots on triple 7’s. The hotel room that Dale books for himself and Redheaded Diane is number 7. At one point, Janey-E calls her life with Dougie! Cooper “Seventh Heaven” and I have alleged that Dale is in the Seventh Circle of Hell […] Seven is a prime number. There are seven days a week, seven seas, seven levels of ‘heaven’, seven graces, seven sins, seven ages in the life of man seven colours in the rainbow and notes on a musical scale. The list could go on infinitely.”

I might add Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), Jacques Lecoq’s seven levels of tension, the seven photograph albums of Eugene Atget, the seven dwarfs of Disney’s film, the seven lives of an Iranian cat, the seven years of bad luck for breaking a mirror (or copying this example from a website!) Seven is also the magic number identified by cognitive psychologist George Miller as the number of items we are able to store within our immediate memory. As such, seven/7/VII/٧/ζ/ז/七/၇/SE7EN is the numerical foundation for all knowledge, upon which civilisations have been built!

BCO inform us that “in seven we have the quality of the specialist, the social deviant and the perfectionist”. This is spoken as a two-second loop of what sounds like an electronic fiddle plays interminable and various high-pitches drones, electronic whines and windy moans distract our ability to make sense of the words that we hear. All of this is interrupted by sounds of pure noise and textural clutter.

This creates a very disorienting experience (much like our Prime Minister telling people to go out to work while also staying at home). As a listener you are forced to pick out the thrumming electric signals and chewy philosophical gristle from the word salad. A heady mix of heteroglossia, schizophasia and echolalia that all leaves you with the distinct impression that you are being trolled.

The Dots’ own side is no less inscrutable, but marginally more palatable for those of us who have listened to all of their output up till 1994 since it is one long restless cut-up of many, many of the Dots’ releases up until that point. It is gratifying as a fan to hear material from the likes of Island of Jewels (1986) and The Crushed Velvet Apocalypse (1990) spliced alongside samples from far earlier work like Kleine Krieg (1981) and Premonition (1982). However, since the Dots have moved through such an array of styles (and varying levels of production quality) the effect never quite coheres to me. The experience that results is a little like that of clicking through one’s iTunes erratically across all of one’s LPD albums without settling down to really sink into the music. I did not really find this conducive to either contemplation or enjoyment, but I still appreciate the experimentation!

Tom: I originally listened to this on the train to Reading and another of my archival research trips on 14 January. That now seems like it was about twice as long ago as the three and a half months it actually was, in our calendars. Subjective, off-kilter experiences of time have become especially mainstreamed of late: funny, that…

The opening side of the Tryst 7 cassette by Big City Orchestra is a deftly edited mixture of drone and sample-collage. This Los Angeles, CA noise band’s offering made for surprisingly serene listening while doing 45 minutes of weeding in our backyard which we hope to sit outside in during our house arrest holiday in a week’s time. Oddly enough, I didn’t get any reaction from neighbours while having it “blasting out” from YouTube via my iPad.

[On one side, admittedly, we wouldn’t have any reaction as the family there are now in Hong Kong. Keeping up routines and making time meaningful has been crucial. Rachel has been getting on with her bioinformatics programming and coding, while getting published in Nature Medicine as a co-author on a paper pertaining to Covid and corneal cells. I have been getting on with my PhD, now halfway through. I received good feedback via Skype on a second draft of my chapter on the Aesthetics and Style of Play for Today and have so far conducted three interviews with writers and actors via Zoom or Skype.

Keeping busy, purposefully so, may sound trite or clichéd, but it’s an important life raft. That said, we are significantly luckier than most. I was going to be going to London on Wednesday 12 March for another BBC Written Archives and British Library research trip. But Rachel rightly talked me out of doing what TV screenwriter and producer Dominic Minghella admitted he did from 12-23 March. I have not been a reckless plague carrier and the only people I have seen indoors at relatively close range have been workers at the local Nisa shop, from behind a plastic panel.]

It’s an enjoyable—and occasionally off the wall—first side. Grave engagement with the connotations of the number 7—a threshold, magical properties, the most sacred number to Hebrews—is then later countered by the surreal materialism of samples. The most memorable is the resounding colloquial American cry of “Raw fish and coconuts!” (c.23:40) This voice claims that many a sailor shipwrecked in the Pacific has stayed alive on these, “Tommy!”

It is followed by the Legendary Pink Dots with a kind of reinforced musique concrète.

Early doors, there’s ghostly aqueous synth, following murmurs of “it’s all gone…”, “face facts!” and cries of “Die with your eyes on!” The latter is from a surrealist past life we certainly do recall. The very first sound is a breezy bright organ tone. There is a grave, wondrous section from 40:38, like that at 32:38 but foregrounded and widescreen. This looped, repeating undertow returns from 47:17 and is so evocative that it plays a trick on the memory: I could have sworn it was repeated far more times! We progress to shards, flanges of backwards sounds and Ka-Spel phonemes. This is all much more changeable in comparison to the slow, almost stately, evolution of Big City Orchestra’s half. But it is unhurried when it needs to be. From 50:57, grave sustained synth notes emerge, chrysalis-like from a noisy fog and lead us to what sounds like the backdrop to “Film of the Book” but notably missing the glacial, beautiful lead melody. The LPDs’ contribution to Tryst 7 is evocatively gnomic and hollowed-out.

In 1994, I was approximately seventeen years away from even being aware of the Legendary Pink Dots’ existence. My cultural habitus can best be characterised as football, cricket, Coronation Street, Doctor Who and WWF wrestling. I also became quite intensely wrapped up in commemorations and histories of the Second World War, collecting a set of magazines and following the media coverage of the 50th anniversaries of D Day in June 1994 and VE Day just over a year later. Adolescence and engagement with cultural undercurrents was to come later. However, the burning wisdom of Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War (published in April 1973), which we read as a class in Year 6 junior school when I was eleven, stayed with me. It’s a great work of children’s literature about evacuation of two London children to Wales which contains the cautionary meaning not to become hardened and insular like the ultimately lonely Mr Evans. In 1993, this book had won the ‘Phoenix Award’ from the Children’s Literature Association as an accolade for the best book that had been overlooked on its publication twenty years before; maybe this influenced it being taken up as the major text in our English lessons, but I recall our teacher telling us that it also been a favourite of hers—she would have been about eleven herself when it was originally published.

Best to forgive, unless they’re Dominic Cummings, Michael Gove, Allison Pearson, Toby Young, Matt Hancock or Boris Johnson—all responsible in their different ways for the UK’s shambolic handling and experience of Covid-19. Also best to imagine Mr Evans having taken a different path and dancing with Mrs Gotobed to Glen Miller records. At a push, you can imagine a cantankerous sixty-something Albert Sandwich playing this cassette and enjoying it immensely.