Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

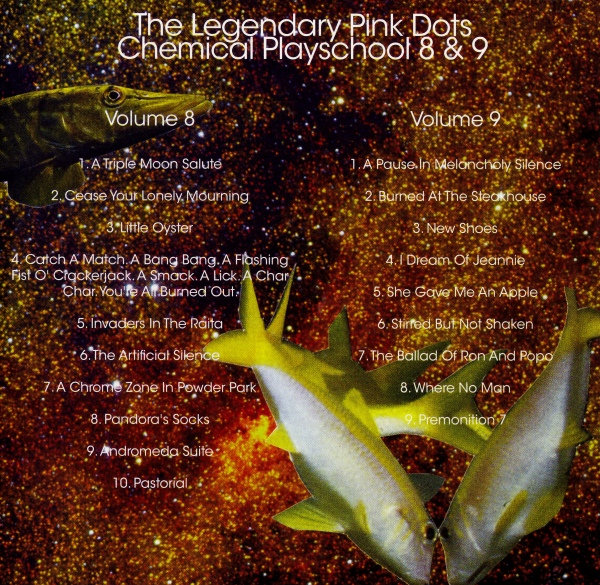

Chemical Playschool 8 & 9 (1995)

Tom: Spotify claims this record was released on 8 August 1995 and its sprawl stretches over 132 minutes, taking in 19 songs. It is the sort of expansive odyssey we’ve come to expect from these Chemical Playschool releases.

It opens with the murky ‘A Triple Moon Salute’. A hazy psychedelic eight-chord sequence repeats very winningly. There are evocative blazing guitar interjections near the end. In the title, space exploration supplants militarism; the lyric seems something of a David Bowie ‘Space Oddity’ or Rah Band ‘Clouds Across the Moon’ scenario, with a narrator desperately yearning for his lady’s return. Glum sepia poignancy abounds. ‘Cease Your Lonely Mourning’ is even murkier; I must admit that this brief segment passes me by.

‘Little Oyster’ has a plaintive Japanese sounding melody, with always-welcome orchestra-hit syncopation. There are Mata Hari references: “With hat-pins baby… pierce me where it hurts, mmm, I love it! I’ll be your little oyster”. EKS does turned-on cheerily in one of those occasional LPD sex-centric songs. There is use of an Orientalist shorthand for Japanese music, but it works as a tremendous, catchy tune, like the Residents, sliced up via judicious orchestra-hits.

‘Catch a Match. A Bang Bang. A Flashing Fist O’ Crackerjack. A Smack. A Lick. A Char Char. You’re All Burned Down.’ Now that’s what you call a song title. It’s repeatedly chanted at that, with pensive, hinting-at-wistful chords in the background. We have more of a subdued, less-of-a-banger spin on ‘Abracadabra’. While a slightly pacier techno remix would serve it well, this is like a chant by the kids in Sapphire and Steel, ‘Assignment 4’ (1981) but who have somehow managed to escape their photographic imprisonment. So it’s laudable.

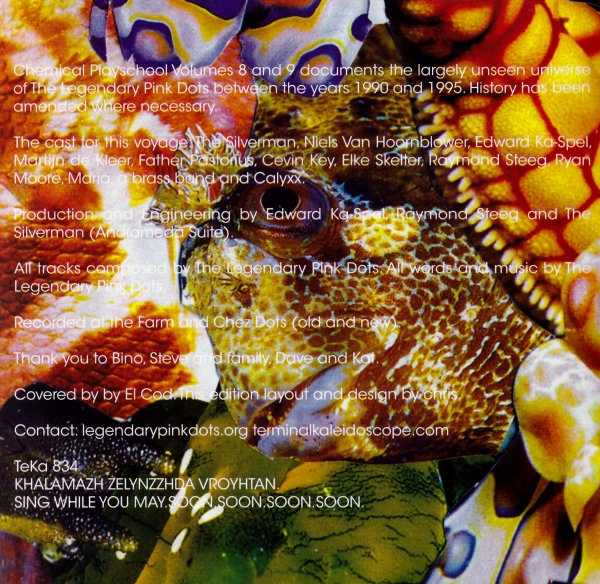

‘Invaders in the Raita’ is wonderfully strange musique concrete, which evolves into a sitar-led Indian excursion with Ka-Spel’s wordless phonemes swarming like a bothered hornet. This is unique even within the LPD oeuvre. Like a ‘Royal Jelly’ (1980) raga, presenting us with what happens after the end of that Tales of the Unexpected episode… It works as a dense, mind-melting 7 minute coda which you sense Timothy West might approve of. This song conjures imagery akin to the record cover: an abstract psychedelic collage that for me evokes Ray Harryhausen stop-motion animation seen through the bleached surrealism of Max Ernst a la Europe After the Rain (1940-42).

‘Artificial Silence’ sounds very early 1980s Dots in its production. This is languid, deft and enriched by squalls of synth after the minute mark. “Crack the silence…” ‘A Chrome Zone in Powder Park’ with its odd syncopated loops reminds me of the Eastern bloc city sequence in the extraordinary, flawed brew that was BBC Birmingham film odyssey Artemis 81, watched – incredibly – by 7 million people in the Britain of 29 December 1981. ‘Pandora’s Socks’ cites Greek mythology. “Things inside me would depress me / Lock them up, you know that’s best / You keep them to yourself…” There’s a chrysalis emergence, but stilled, suspended in time, after the minute mark.

‘Andromeda Suite’ concerns military recruitment: “be who you want to be” lent a stark irony. “Imagine there’s no heaven…” Then we are in a monotonous, dank tunnel. Elements of suspense infuse a dense soundscape before the 9 minute mark. Who else but the Dots would nestle a truly catchy fatalist refrain which begins “It’s a long way to Andromeda” amid what is primarily 20 minutes-plus of musique concrete? It feels a tremendous, hard-won moment when Ka-Spel’s vocals return. It really is a counterpart to David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ but filtered through Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hawkwind. The finale is becalmed, stately and gently serene.

‘Pastorial’ has an autumnal feel. End of summer holiday. End credits for a great TV movie. Satisfied, yet wistful. ‘A Pause in Melancholy Silence’ is a plangent, uneasy guitar-led song which evokes John Fowles’s novel and film The Collector (1963/1965). Again deftly produced, if not quite as atypical in a sterling way as ‘Pastorial’. ‘Burned at the Steakhouse’ asks: “Who needs a perfect planet anyhow?” and refers to “All art of the service…” The ‘stakeholders’ of a service sector-led economy are carnivores. This seems, to me, a critique of many people in the 1990s for their rejection of socially conscious values, their speeding into nihilism. There seems an important message, but perhaps too little spry play in the song musically.

‘New Shoes’ feels like late 1970s Eurodisco slowed to a Goth hush, Space’s ‘Magic Fly’ (1977) or Jean-Michel Jarre’s ‘Oxygene, Pt. 4’ (1976). This is a construction concrete, its juddering bass like Pink Floyd ‘One of Those Days’. A plangent minor-key instrumental tour round the spaceways. Tidy. Initially, ‘I Dream of Jeannie’ has a Residents feel, with glazed Lynchian guitar. “Dress her in the blackest flags…” There are battered Chevrolets on every street and every corner. “Cigarettes are vile” causing teeth now to be yellow-brown. “Another Yankee in the jail, another movie, one more headline”. This last phrase is repeated, ever more scornfully. Using “you, again and again”, the lyric points to the human being becoming instrumentalized.

The following ‘She Gave Me an Apple’ is one of those deft LPD celestial sea shanties. Circling, crystalline music as Ka-Spel speaks of acid rain, Jesus returning, generals betokening war. “The machine”. Satan returning. No one paying attention. “The world concluded happily, so there…” Neat stuff, but seems a little fragmentary, and could have done with being lengthier and more developed.

‘Stirred But Not Shaken’: horns, a slow beat, I don’t have much else to say about this one. ‘The Ballad of Ron and Popo’ seems wilder, a free floating, unmoored construction, everything decentred. It’s a classic ironic title, as we hear loops, indistinct environmental samples and musique concrete shards and bleats. Eventually, there is a hazy keyboard pattern connoting an approximated music box. We hear distant soloing guitar behind the mesh fencing of gauzy static.

‘Where No Man’ presents a tuneful, minor-key with Ka-Spel recalling “another age” and a “neon palace”, and whether we escaped or are we tourists, peasants lying in their graves… Synthetic swirls graffiti over a questing, querying guitar led by horns. There is a tyranny of “five stars”, a new world of bland critical appraisals led by the numbers. “We never ever shall return!” is followed by frenzied, luminous musicianship. Then, a factory interlude and into a suspenseful, wistful finale. It feels like an odd centrepiece.

‘Premonition 7’ is over 22 minutes, starting with a distant soundscape. It gradually becomes more distinct, with hazy, submerged brass band particularly evocative after the 10-minute mark. There is even a hint of experimental, decomposing Derek Bailey-like guitar playing from around 13:19. It all evokes, in a strange way, the halting of the forward march of the Labour movement, which sadly hasn’t yet been reversed, even in 2021. Overall, this does comprise a compelling and atmospheric instance of ambient Dots.

Chemical Playschool 8 & 9 is another disparate gazetteer: for me a very impressive release aptly accompanied by wonderful album cover artwork, which evokes collaged Max Ernst and Ray Harryhausen imagery. Do any Dots records have human faces on the cover? I am probably forgetting loads which do, but they don’t immediately come to mind. Maybe that’s telling; maybe it isn’t, or even true! Narcissism is in the fire, with the tabloid faces.

Adam: When Tom writes “Do any Dots records have human faces on the cover?” I presume he is referring to the faces of the band members. Otherwise Asylum (1985) has realistic but distorted inmates and prophets, The Maria Dimension (1991) has many Marias, Malachai (1992) has a mysterious figure in the flames surrounded by the grinning death masks of chattering skeletons, etc. The only album that has humans who might be mistaken for band members is A Perfect Mystery (2000)… appropriately so, since that album was the first in a long time in which the band developed ideas together in the studio, rather than building upon each others’ individual contributions. The people on the cover aren’t the Dots though. Humble indeed!

The first track on the Dots bandcamp page for Chemical Playschool 8 & 9 reads ‘A Triple Moon Salute/Cease Your Lonely Mourning/Little Oyster/Catch a Match/Invaders in the Raita’, compelling me to treat them all at once as some kind of interlinking suite. Actually, musically these tracks are very different, but they are united by a Maria Dimensions-period concern with esoteric rituals performed outside the constraints of institutionalised religion… spiritual awakenings or just brains on the fritz? Either way, our ears open upon a rainy war parade with soldiers down on their knees. There is a Pachelbel-like melody, intruded upon by thrumming synths. We are perfectly poised between pathos and bathos before the assembled ranks topple down like dominoes, “Floored by the tripwire/ Stripped by the crossfire”. We did not awaken upon a military parade, but a sermon inside a crashing databank. Is the singer speaking his devotions to Mary, Lisa, or some other mysterious Lady of air and whispers? The rising digital murk soon obscures all until it sounds like three different His Name Is Alive tracks played at once, headphones glued to my ears.

‘Little Oyster’ is a weird kinky little ditty, its slippery seafood squicky-sexiness recalling Asylum’s ‘Fifteen Flies in the Marmalade’. There we had “Will you dance with me my little pickled herring?”, here we have “I’ll be your little oyster”. Musically it reminds me of some of the Japanese court music used in Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book (1996), an erotic drama no less polymorphously perverse than this track, but a little less craven about it! It is a festering hot tomato of a song, but I can’t help but feel that what seems like a heady stew at first seems more like thin gruel when you realise that its component parts are regurgitated from older, stronger songs.

‘Catch A Match. A Bang Bang. A Flashing Fist O’ Crackerjack. A Smack. A Lick. A Char Char. You’re All Burned Out’, however, is remarkable. The experience of hearing it for the first time is akin to being confronted by a group of itinerant subway preachers and finding yourself deeply moved by their echolalic nonsense poetry. The deep, dark abyss of chanting recalls the “tribalistic” ‘Green Gang’ from Crushed Velvet Apocalypse (1990), but the impact is closer to the very strongest, most emotional track on the Residents’ maligned The Big Bubble: Part Four of the Mole Trilogy (1985), ‘Cry for the Fire’. Eventually the chanting is subsumed by what I can only describe as the sound of a hive of electronic bees being gassed to death… or maybe the Autonomous Drone Insects from Black Mirror, ‘Hated in the Nation’ (2016). ‘Invaders in the Raita’ starts, unpromisingly, with the sound of one of the Dots dabbling with a sitar. At some imperceptible point this noodling becomes a spiritually transportive vertex of sound that channels Om (ॐ) as effectively in its own way as Battle Trance’s saxophone drone opus Palace of the Winds. And then, at another barely perceptible point, the listener finds her/himself at a séance at the Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) family ranch, without knowing how on earth they got there. How do the Dots go from dicking about to absolute sublimity to bug-eyed chaos within minutes?

I don’t know how many times I have mentioned ‘The Island of our Dreams’ before even getting to Your Children Placate You from 2006, but ‘The Artificial Silence’ is a precursor to it in its blissed out melancholia. It sounds of a piece with other bands of the mid-’90s, though my musical knowledge falters and I cannot say exactly who… Lemon Jelly, maybe… Zero 7… Nightmares on Wax? The next track, ‘A Chrome Zone in Powder Park’ is much easier for me to situate, recalling – as it does – the velvety somnambulistic beats of Massive Attack. When we leave this auditory mezzanine, we drift into a stormy radio fuzz transition. A few years ago I accompanied some amateur ghost hunters on one of their nighttime sojourns through the outskirts of Ipswich. We ended up underneath the Orwell Bridge, a common suicide spot. They tried to tune into the voices of the lost souls via ghost detector software apps on their phones with names like iOvilus, Spirit Board and Ghost Radar. Anyway, this track sounds like it was created with samples from ghost detector software.

Finally, ‘Pandora’s Socks’ begins as a music box lullaby – the kind of melody used to great effect on the soundtrack to Henry Selick’s stop-motion masterpiece Coraline (2009) just over a decade later. Around two minutes in, the track transforms into a psychedelic wig out that recalls late-period Van Der Graaf Generator or mid-period Pink Floyd, even Ozric Tentacles, overseen by the ghost of Frank Zappa’s Central Scrutinizer.

Things then get highly psychotropic for the consciousness-expanding ‘Andromeda Suite’, a cosmic trip on a spaceship travelling through inner meatspace. I picture the Tyrannosaurus rex voyager from Kazuo Umezu’s Fourteen (14歳) or one of the sensory deprivation tanks from Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980). It is a track you have to allow yourself to sink into, but it really pays off once Ka-Spel gets to singing the cathartic line “It’s a long way to Andromeda”. ‘Volume 8’ finishes with the gorgeous ‘Pastorial’. The track is only three minutes long, filled with elegant finger-style guitar and – perhaps – a subtly wafting theremin. It is pure beauty, earthbound where the previous track was cosmic. You can imagine listening to it on a Hellenic island next to an iridescent pool of water.

Volume 9 is a zippier, more straightforwardly enjoyable volume than 8, though without such depths of emotion or moments of transcendence. ‘A Pause in Melancholy Silence’ should be classic mid-90s Dots, but doesn’t develop in interesting enough ways, remaining a flower that never blossoms. It sounds as though it was left on the cutting room circa the 9 Lives to Wonder (1994) sessions. You can picture Ka-Spel sat on a boho hippie rug (or maybe just a rolled up kaftan) with a pair of bongos and an acoustic guitar. The narrator of the song could be characterised as a reflective mildly perverted hippie, which isn’t the most enthralling character in the Dots stable to date!

‘Burned at the Steakhouse’ is a lot more fun – slinky and horrible – until you realise it’s about climate change and ecological devastation… from the point of view of Big Oil. It is hard to take too much ghoulish glee in this when one is listening in a month in which the IPCC has declared that even under the most optimistic scenario of radical decarbonisation there would still only be a 50% chance of restricting global warming to 1.5 °C. When normally cautious scientists of the Oxbridge establishment like Professor Tim Palmer say “Our future climate could well become some kind of hell on Earth” you have to be really determined to keep your head in the sand to not be terrified.

The music here sounds phat and oily, recalling the olfactory wheeze of ‘On the Boards’. Here, though, the impression is more oil factory than olfactory! To give you a better impression of its distinctive groove, I was listening to the album while working on some admin at my library job and when I got to this track, I actually thought that a piercing alarm going off in the building was part of the sound design. Most roughly textured is the intrusion of a rasping kazoo… or maybe a tissue over a comb with pursed lips over it making farting noises. It might be an actual wind instrument played by van Hoorn, but it definitely sounds abject and bodily.

Far more palatable is ‘New Shoes’, an atmospheric underground jazz groove with a nicely spiralling bass line, Už jsme doma meets Saucerful of Secrets (1968) era Pink Floyd. It ambles along intriguingly. We have discussed ‘I Dream of Jeannie’ before, but this is a beefier, more overtly menacing take on the earlier Dots classic. It becomes a trifle ponderous by the end, but is mostly animated with a sinister animus. ‘She Gave Me an Apple’ is a lovely weird fish of a song. Hypnotic and beguiling. I rather wish it has been left as an instrumental since Ka-Spel’s lyrics tie the music down to specific imagery with the decidedly unromantic apocalyptic/militaristic concerns of Island of Jewels (1986).

‘Stirred but not Shaken’ is appropriately difficult to imagine being sung by James Bond. The lyrics are sad and introspective: “Tossed by the wind of relief and regret, I’d turn right, twist left/ I was caught up in a net.” If Autechre had gotten into soundtracks in the ‘90s the results might have sounded like the skittery ‘The Ballad of Ron and Popo’. It is a (purposefully?) unsatisfying track, skimming along the surface of circuit boards rather than really diving deep into the mainframe. I suspect it would be effective as the music in an AMV (anime music video) set to clips from Serial Experiments Lain (1998). At the end of the track, we are gifted a snatch of wistful Gamelan-like chimes as though misremembered by a robot from a Balinese folk song… plus unexpectedly wanky guitar playing of the kind Chowder Man would play! [Ed. The guitar playing is epic, just flamboyant). ‘Where No Man’, meanwhile, is another wet and funky visit to Hell. This is perfectly placed before ‘Premonition 7’, the final track of the compilation, since it sounds like a field recording from the blasted dystopian cityspaces of David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977). While Fats Waller played the organ on some distant gramophone in Henry Spencer’s purgatorial apartment, here it sounds like the Dots’ own ‘Tower 2’ that is being played miles away in the distance. This is something of a return to the eerie soundscapes of 1982’s Apparition. Indeed, I can easily imagine the track playing on the soundtrack of a film adaptation of Luke Smitherd’s urban ghost horror novel The Physics of the Dead (2011). More organic textures only intrude towards the end of the piece… and even then they seem to be courtesy of a sampled ghost child – perhaps the same entity that haunted the recording of Apparition.

‘Premonition 7’ is a very low-key note on which to end such an unruly, brilliant album. It is not the strongest of the ‘Premonition’ tracks, but it comes at the end of what might be the strongest ‘Chemical Playschool’ release to date.