Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

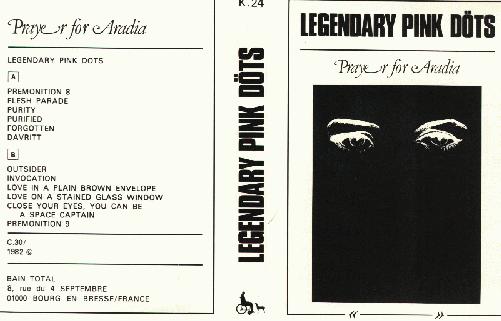

Adam: So, we’ve come unstuck. We’ve reached 1985 and yet here we are again with the familiar low-fi fuzziness of the very earliest incarnation of the Dots. Out of time, yet not out of order. Prayer For Aradia was released in 1985, but it had been recorded three years prior. As though they’d never left, April White is here playing her icy arpeggios on ‘Forgotten’; Keith Thompson plays an honest-to-God real-life drum kit on ‘Purity’, with all its organic imperfections and tactile timbres; Roland Callaway and Michael Marshall provide pulsing post-punk bass and electric guitar, respectively. And there’s nary a sign of Patrick Wright’s violin, which so dominates the Dots’ early-mid period. After Asylum (1984) we are on much safer ground – less arch; more immediate; more straight-forwardly enjoyable.

However, be that as it may, Prayer For Aradia still provides a unique challenge to the reviewer – namely, that it is one long mix, with the songs bleeding into and contaminating each other. The album is like an impressionistic canvas that warps and shifts before your eyes. It is hard to get a solid grasp upon. The album begins with the eighth iteration of the ‘Premonition’ series. A mechanical thrum retreats before washes of electronic synth, flooding the system like an anesthetic. The cosmic, yet heavily synthesized sound that results (overlaid with occasional blips and bloops) is uncannily similar to the ‘Space Intro’ of the Steve Miller Band’s 1976 album ‘Fly Like an Eagle’ – a resemblance that I can only assume to be wholly coincidental. Cut into this emerging soundscape, however, is an unambiguously intentional reference in the form of a sample (“They’re here…“) from the film 1982 horror film Poltergeist, a release which would have been contemporaneous to the recording of ‘Premonition 8′. I suspect this is little more that a playful evocation of the haunted ambience of the Dots’ records, getting the viewer in gear for what they should expect, eliciting a wry smile and perhaps a touch of the spooks. However, I also recall my Mubi review of the film: “A haunted house movie chaperoned by the ghost of Ronald Reagan”. Poltergeist is a movie about the impossibility of living authentically within a homogenised, hyper-normalised, aggressively insipid culture. It is not for nothing that the film’s protagonist is a pot-smoking ex-hippie forced to sacrifice his integrity for his career in real estate and that the film’s ghosts enter the household through the omnipresent television set.

It is apposite then that many of the songs mixed and half-hidden within Prayer For Aradia seem to be concerned with the difficulty of reaching pure states of love/religious enlightenment when these states are: 1.) saleable as commodities, 2.) often difficult to divorce from reactive attitudes. The first difficulty (the commodification of love) is examined in the thematically linked ‘Flesh Parade’ and ‘Love in a Plain Brown Envelope’. The stulifyingly monotonous, but invitingly textured ‘Flesh Parade’ depicts an endless chain of fleshy couplings divorced from compassion or human feeling, each partner interchangeable with the last. It is a cynical, mechanical vision – the ending of Brian Yuzna’s Society (1992) played out in cold rooms minus any orgiastic fun. I previously discussed ‘Love in a Plain Brown Envelope’ when looking at the Faces in the Fire EP (1984). The version here is sparser and less developed, dating from an earlier recording session.

Elsewhere, on Part 2 of Prayer For Aradia, fingers slide across the metal strings of a guitar, alternating with a simple finger-picked melody, which gives way to a funky variant of REM/The Smiths/Echo and the Bunnymen/’s 1980s jangle guitar sound. So begins ‘Outsider’, an eerie, but slightly plodding vision of religious persecution. Religious belief may begin with an authentic experience of the sublime, but the primitive in-group/ out-group dynamics that govern human interaction ensure that sooner or later those who don’t adhere to the particular creed of a given religion will be ostracised, excommunicated, or executed. Ka-Spel suggests that the reptilian brain squats at the base of such persecutions: “Don’t know what you did, but I don’t like it. Something about your eyes says you just don’t fit.” It is a convincing assertion, but a simple one, divorced from both social history and economics. It is an argument made many times over by the likes of Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins.

That is to say, the younger Ka-Spel’s lyrics are not at their most developed here (especially not in the wake of The Lovers or Asylum). ‘Purity’ is something of a stock L.P.D. character study of a zealot seeking to watch the world burn. He cuts a more cartoonish figure than the sinister, desiccated generals that populate The Tower (1984) and its thematic follow-up album Island Of Jewels (1986). Still, the zealot’s mission of absolute purity comes from a similar categorical imperative to that which drives the religious persecution of ‘Outsider’. Cut off any parts that might be diseased. Identify and isolate the deviant or dissident. Impose order over chaos and freedom by whatever means necessary.

It is perhaps easier to grapple with the lyrics of Prayer For Aradia than its music, which is often so spacey, gloomy, or murky that it becomes a fool’s errand to distinguish all the instruments (or, rather, the sounds of different keyboard and synthesizer settings) or isolate when one song ends and the other begins. ‘The Flesh Parade’ transitions into ‘Purity’ with what sounds like a gun fight in an underwater arcade. The latter track is mostly distinguishable by the devilishly propulsive bass-line in the verses and the almost jarring melodiousness which characterises a repeated passage that lies somewhere between a bridge and a chorus. The end of the song is decidedly less tuneful and sounds as though one of the Dots fell into a keyboard. Thankfully, this is quickly replaced by a cod-ecstatic, Heavenly wash of synths that recalls every ice level of every platformer ever made.

It’s not that Prayer For Aradia sounds clichéd per se but rather, through attempting to (very self-consciously) occupy a mythologised space with both its lyrics and music, the material acquires a certain level of bathos. Arguably, this is deliberate. After all, ‘Purity’ gives us the figure of a street-cleaning zealot-cum-vigilante; ‘Forgotten’ imagines a fragile and forgotten King Arthur whose Albion innocence is out-of-step with the modern times; ‘Space Captain No. 1’ is the tale of a drug addict praying for enlightenment at the end of a needle.* The music reflects the murky, delusional dreams of these characters. Icons think in clichés. However, in my opinion, it makes for a less vital listen than the relentlessly inventive (though spotty) Asylum. So it goes.

*One thing that has surprised me listened to the Dots is that Ka-Spel’s lyrics seem ambivalent, at best, about drug culture. Starting the project, having listened to the likes of 1991’s The Maria Dimension, I had rather assumed that Ka-Spel was a psychonaught in the model of the late Terence McKenna. In actual fact, druggies in the Dots’ output are generally portrayed as delusional, narcissistic, and often end up dying from an overdose or suicide. Sometimes the impression one gets even borders on the censorious.

In fact, the only track on Prayer For Aradia which I would whole-heartedly recommend the reader buy is the glorious ‘Premonition 5’, which makes your speakers sound as though they are possessed. This is the kind of stuff that the Dots are masters of. There is a touch of Goblin in the chanting and the gloaming and the emphasis on timbre over melody bears affinity with Throbbing Gristle and Nurse With Wound, but this also happens to be gorgeous. If anything, it sounds like the music the evil doppelgänger of Brian Eno would make. Try pairing it up with ‘Absolutely Curtains‘ from Pink Floyd’s Obscured By Clouds (1972) to experience a movement from dappled Druidic sunlight into an atmospherically charged twilight. Strings lilt and mourn. Guitars played finger-style circle and repeat. Then, around six minutes in – and this is sublime – the guitar from Only Dreaming‘s ‘Voices’ (1981) is played forward over what I believe is the melody from Brighter Now‘s ‘City Ghosts’ (1982) played backwards. Both of these songs would be in my personal top 10 LPD songs of all time so, for me, this moment is just glorious. Deeply haunting and very pretty.

If I were to recommend the Dots initiate the material they should purchase representing the Dots’ very early career (1981-1983) up to the release of The Tower in 1984 (where commences a brilliant run of albums if you discount Prayer For Aradia), I would suggest they buy the 1997 compilation Ancient Daze, upon which Only Dreaming is heavily represented; the daunting but magisterial Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 (1983); and ‘Premonition 5’ which, though technically from 1985, is, in practice, from 1983 at latest.

Tracks 16 through to 23 of Prayer are all taken from Chemical Playschool 1 & 2 (1981), which were discussed in the review of that album. That said, I must say that while Tom finds ‘Temper Temper’ to be very slight, I really like the combination of forced jollity and homicidal rage. It is disturbingly chipper!

Finishing off the remaining original material – ‘Davritt’ sounds like a bunch of street recordings taken on sunny, but overcast days. A busker plays a lilting sax while church bells rings. ‘Invocation’ is a muddled, but vaguely disturbing vocal soundscape. ‘Premonition 9’ is a cold and rumbling glimpse of a subdued Hell. I like the voices modulated to a ludicrously low pitch. ‘A Spanish Bridge’ is a piece of Spanish-style guitar set to an almost Gamelan-like congregation of synth sounds. It is pleasing, but utterly inessential. Finally, ‘Stoned Obit 1980’ bounces along hauntingly, but with less visceral effect than in its latter form as ‘Stoned Obituary’. The title suggests what a very early track this is, recorded in the very first year of the Dots’ existence.

Now, finally, with the end of the album, old ghosts are laid to rest and a new dawn may begin.

Tom: The opener ‘Premonition 8’ seems like a soundtrack lifted from a film. I am imagining the film as a crazed, skewed take on Hollywood’s ‘the aliens have landed’ trope. “They’re here!!” indeed. Maybe they are, if they are incomprehensible phantasms…

Crucially, ‘Flesh Parade’ has distant, sampled choral sounds – which fade in and out imperceptibly. It is a glum, captivating dream vision of prostitution and anomie: “She likes a man, but a hand is just as effective. A mutual need. No need to talk. No moonlit walks, no sun-drenched beaches. Just a bed and just an alarm clock, says your time is up.” This questions the human-derived concept of time and the clock used to quantify and monetise urges and desires.

It is disquieting, as anything about social and sexual atomisation should be, with vocoderised synths proceeding like griping, grudging train carriages. It also reminds me of the third episode of Louis Theroux’s first series of Weird Weekends, from 1998, where the BBC-2 presenter encounters what is signified as an ultimately depressing world of pornography. The clean-cut, cheery Godzilla film fan J.J. finding it preferable to the army and unable to imagine doing anything else, despite the horrible stress of having to produce “the wood” to order for money.

‘Purity’ has talk of cleansing and catharsis, bringing to mind that misguided avenger Travis Bickle. There is more sense of the post-human with the verb phrase “piston legs steam on”, and typically paradoxical noun phrases: “cleansing petrol” and “a lullaby of hysterical laughter”. ‘Purified’ is a briefer than the blink of an eye instrumental passage.

‘Forgotten’ is one of those dazed, psychedelic LPD lullabies which continues ‘Purity’’s theme of would-be saviours. A tale of a worn-out, weakened, out-of-time King Arthur: “[He] Tore up the script. He tried to save us, but he failed. ‘Cos everybody laughed: the rusty sword, the rotted table.” It implies a non-Christian, even Pagan Arthurianism: “Other times, when he was good, he wore a crown of orchids. Take his lady, sow his seed, it’s for the harvest; gardens bloomed. No one mentioned heresy or blasphemy.”

Into ‘Prayer for Aradia (Part Two)’; we’ve heard ‘Outsider’ before – ‘The Heretic’ from the previous year’s The Lovers. It seems all the more plugged into English myth in its place on this album: an Arthur made strange, followed by an excursion into Hammer horror influenced synth pop. Then, a reprising of ‘Love in a Plain Brown Envelope 1’, with its cyborg ‘mean machines’; as Adam says, it is embryonic. Next is an instrumental ‘Love on a Stained Glass Window’, brilliantly named, and with oblique, murky found-sound vocals.

‘Space Captain No.1’ depicts a forlorn, bedraggled cosmonaut, whose plans have come to nought. There is mention of a ‘gentle voice encouraging: “Take them now, finish it, yes, you can be a film star, you can be a star, you can be anything you want to be.”’ Panaceas and cornucopian promises oddly redolent of those you would see Further Education colleges in north-east England offering in the late-90s, early-00s. “BE WHOEVER YOU WANT TO BE” – the bedazzled, aspirational individualism of those times where neoliberal hegemony seemed most secure of all. All of which gets me thinking of when I was 17 and dreaming of past times less tranquil and sedated than 1999 or 2000. I was fascinated with discords and flipsides; in February 2000 saw the dark, naturalistic BBC-1 drama Nature Boy – filmed in Barrow and all sorts of northern bleak spots – and, in March, Jam came to Channel 4 and the edgy Morris-Iannucci satires I had got into the previous year became all the more present tense. I had found my habitus, oddly enough around the same time as when studying Bourdieu in A Level Sociology at my local Sixth Form College.

While ‘Space Captain No.1”s panaceas are clearly more drug than College based, I feel at liberty to interpret it in the light of my own mundane experiences.

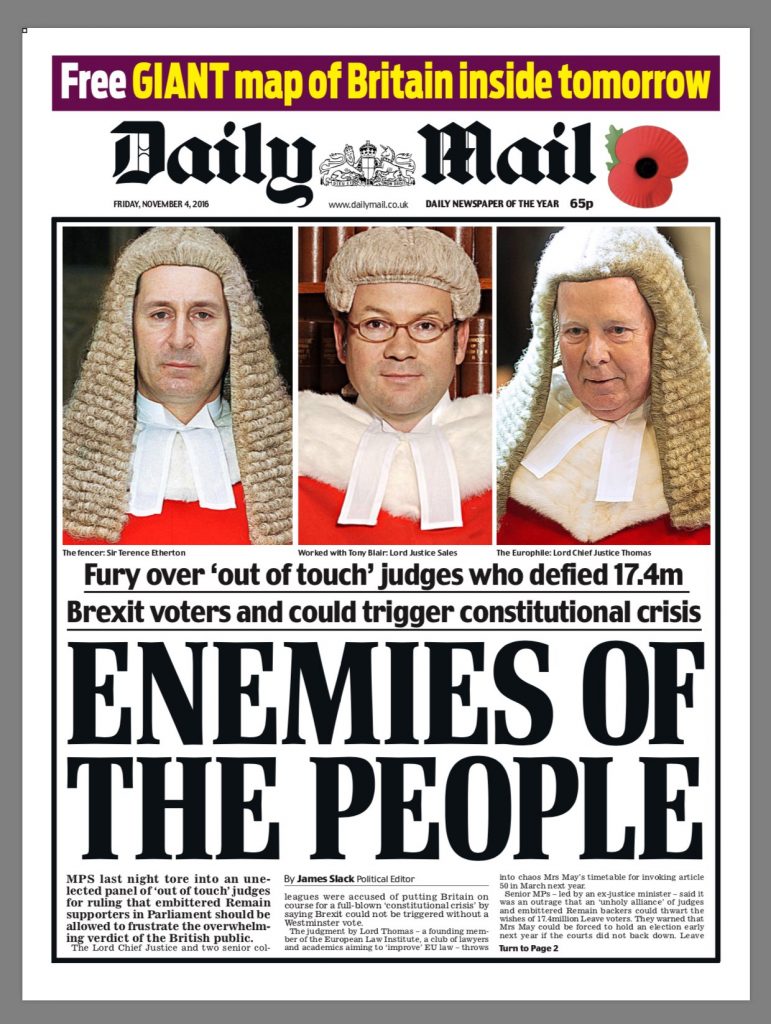

Next, we get the instrumental ‘Premonition 9’ – with a stalled space-flight, faltering fireworks and a vaguely mournful saxophone. ‘Premonition 5’ continues the fresh material with a loose guitar and violin soundscape joined from c.2:45 by a distant, sampled choir. It is beautifully just drifting, to quote Psychic TV, and like a 1930s dance hall tune, the lyrics enter very late – while the music has shifted into a faster mode – at 6:10; though it’s hard to imagine Al Bowlly crooning these opening lines: “He never had a chance, the trap was good, the exits covered.” It’s another dark scenario which seems to tackle the corrupting sensationalism of the British media, which does its job to pacify and dupe the population: “A present for the alley god, who switched his TV off, opened up his window, said “I’m pleased, so very very pleased.”.” This can be seen in the context of the ever increasing power and influence for Rupert Murdoch in the UK: this album being made right in the midst of the Thatcher ascendancy: 1982-88. There also seems to be a passing reference to the “video nasties” row of the early-mid-80s and the then-current debate over violence on television. Suitably enough, the track veers off into backwards vocals and repeated tolling bells.

‘A Spanish Bridge’ is a deft, if slight instrumental, with vocoder sounds dallying with repetitive guitar notes. ‘Stoned Obit 1980’ opens with a looped odd refrain and estranged, background screams. We are presented with a more basic version of what we heard on Kleine Krieg (1981), very much in the lo-fi recording style of Only Dreaming (also ’81) – which is pretty jarring in the context of more recent albums’ relative polish. It fades out in vocoderised calm.

Another oldie, ‘Peace Krime 2’ gives us even more vocoder and that mind-numbing repeated Thatcher loop, which feels inescapable: “Crime is crime is crime…” ‘Professional’ also seems familiar – and I gradually realise it is from Chemical Playschool 1 & 2. “There’s wars to fight, there’s claws to bite. Some things you have to stifle. It’s just a job, a profession.” It outlines a reluctant person’s embroilment in war and fighting and selling his body to the snipers. Bodie and Doyle, this is not! As anyone now who watches or analyses the vastly popular 1977-83 ITV series The Professionals would gather, the term ‘professional’ is made comic book in the broadest possible sense, but without the deliberate camp and self-mockery of that other Clemens series, The Avengers. Where that series tends to endorse a sort of SAS-fetishising totalitarianism, Ka-Spel is more deliberately unnerving, evoking an uneasy calm and de-sensitisation, rather than laughable macho assault course antics: “There’s wars to fight, there’s claws to bite. Some things you have to stifle. It’s just a job, a profession.”

‘Brill’ breaks out into a berserk ‘Revolution No. 9’-style clash of samples and tunes (from previous LPD releases?), and continues as thus for neatly six minutes. We then get ‘Sensory Deprivation’, which we have had on Chemical Playschool 1 & 2 in 1981, and I can’t recall any difference in this version from that. And then ‘Temper Temper’, which seemed to pass me by on the same 1981 compilation and it seems very slight next to some of what we have heard on albums like The Tower, The Lovers and Asylum. As indie-electro-pop, it isn’t quite Scritti Politti’s ‘“The Sweetest Girl”’ or The Passage’s ‘XOYO’. ‘Ampitheatre Shuffle’ is another shared with CP1&2 – can only add again that this is pleasant, wistful soundtrack music. ‘Before the End’ is excellent, and I hadn’t remembered it much; oddly, considering it was on two previous releases, including Only Dreaming! It is like Syd Barrett given a socio-political bite, which is a marvellous thing: “The pubs rang out with “Auld Lang Syne” as a politician tossed a coin.” Rather less marvellously, it hits home in a Blighty of 2016, where politicians want to decide on critical issues that will affect our lives for decades without parliamentary scrutiny. And are cheered on by the sort of mob law-inciting media represented dramatically by Henrik Ibsen back in 1882:

The closing ‘Fin’ is a return to pointillist, dotty synth psychedelia and I don’t know whether it has turned up before in the Project; Adam may know more! Prayer for Aradia only has a few tracks new to me, but they are all consolidations of key tendencies in the Legendary Pink Dots’ music. They are “old”, however, in the context of where we are headed, so it is now good to head into the then-present tense of 1986…