Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

All the King’s Men (2002)

Tom: This 65-minute album was released on 24 September 2002, as my often turbulent second year at University commenced, after a fairly pacific first year. Specific attempts to throw yourself into life are never easy, but are essential. I made attempts and have kept failing better, by and large. I was listening widely at this time, but was still well away from discovering the Dots. I was especially into Saint Etienne, anything involving Luke Haines, Robyn Hitchcock and those tremendous pop art jazz Surrealists the Bonzo Dog Band…

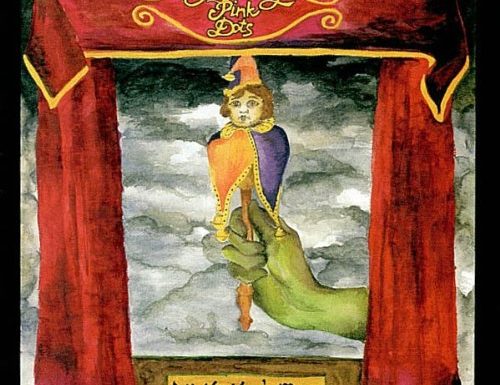

The album cover evokes puppetry, with a figurine of a child in an archaic hat and orange and purple cloak, its edges embroidered in gold. The “body” of this urchin is a wooden stick, clutched with sureness by a mysterious green hand whose arms snakes off to the right. At the front are theatrical curtains, with the band’s name at the summit and the album title nailed to the wooden floor on a gold plaque. The stage backdrop is of grey clouds, with patches of white and black. This artwork has a basic, naïve and enigmatic quality which creates the expectations we will aurally witness a strange show.

-

‘Cross of Fire’ has a fizzing, spindly production, if a touch underwhelming. While you have to appreciate the insectoid bleeping, it just doesn’t ignite or draw me in sufficiently.

-

‘The Warden’ – Horror film organ beckons us into a more welcoming forbidding tower. This is rather more like it! (And what was promised by the album cover) This isn’t so much dungeon synth – a fine musical sub-genre – as spiral staircase synth.

-

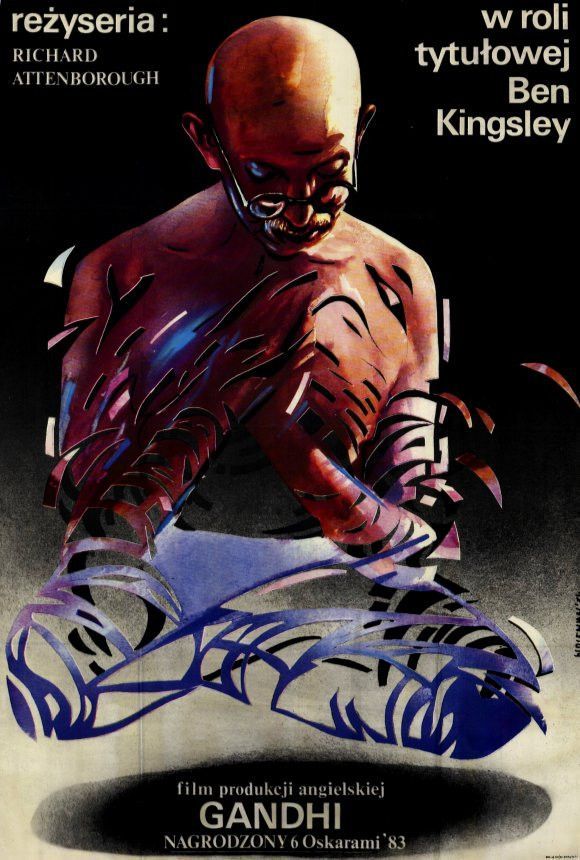

The Polish film poster for Gandhi (1982) ‘Touched by the Midnight Sun’ – “Drive me MAAAAAD!” Tympanic fanfare, black bands on our arms. “The army fired once. The Queen was looking very, very sad…” This is aptly backed by sampled submerged military trumpet sounds. John Donne’s ‘No Man is an Island’ is intermingled with the British Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’. Good, beatless atmospheric piece which immerses us in downbeat war. I’ve recently watched the excellent cinematic epic Gandhi (1982), wherein Richard Attenborough, John Briley, Ben Kingsley and the cast and crew’s multitudes evoke a historic leadership of non-violent resistance and forward an unbearably moving anti-sectarianism. This song’s muffled, aptly muzzled military fanfares make me think of one of the film’s many crucial lines, delivered by actor Geoffrey Chater, delivered to Edward Fox’s guilty man of history: “General, how does a child shot with a 303 Lee-Enfield “apply” for help?”

-

‘Rash’ returns to the low-key synthetic sound of the first track. There is fairly enervating lead guitar in the space rock mould, but it all feels a tad grounded via its minimal electronic percussion. To me, this feels more like a few stray insects than a swarm.

-

‘The Day Before It Happened’ is, again, initially, low-key instrumental stuff; though, this does feel like it might make an apt, mildly unnerving underscore to an odd film. Then after 100 seconds, Ka-Spel enters the more songlike second part. He tells of a village being flattened, by missiles, by mistake. This scenario is appallingly resonant with the horrific arbitrariness of warfare in the 2000s “War on Terror” era. Soldiers were ill prepared and equipped, for missions which were morally contorted in line with our leaders’ confused, hypocritical ideologies. This song feels like a bridge between the Dots’ early Second Cold War dread of nuclear war and the subsequent events in Iraq. Horribly prescient.

-

‘Brighter Now’ marks a return to early 1980s Dots! And, while in common with much of this album the production feels a tad under-furnished, it’s carried off pretty well, preparing us for the final track, ‘The Brightest Star’.

-

‘Marz Attacks’ is one of the finest Dots instrumentals I can recall hearing. This is an energised Neu!-like exploration with pointed, blazing Michael Tother-esque electric guitar. Aptly stratospheric and beat-less: a brilliant drift or cluster in the cosmos.

‘4000 Dead…The “Mission Accomplished” Clock (with no hand…)’ by Tony Fischer -

‘Sabres At Dawn’ feels very bare and sonically minimal after ‘Marz Attacks’ and before what will succeed it on this unique Dots album. It’s squarely occupying that uneasy nursery rhyme territory of ‘Fifteen Flies in the Marmalade’, but does not really go out there enough, for me.

-

‘All The King’s Men’ is the first of two ten minutes-plus epics that end the album. This title track and vast ambient soundscape takes us into vast, undiscovered climes. Strangeness is summoned: from churning electronic musique concrete to a unique extrapolation from the nursery rhyme ‘Humpty Dumpty’. Yes, clearly: it’s an essential headphones trip. “Behold the New Man…” and a “superman” are, surely, Nietzschean allusions: a philosopher heavily in vogue in US indie films from the 1980s-2000s. New Egg, let’s be ’aving y’!

-

‘The Brightest Star’ contains more motorik relentlessness. While I liked the title track’s deft, scrambled esoterica (or eggs-oterica?), this is a relentless, glorious mess. Martijn de Kleer’s violin adds ornate texture to this juggernaut, vying with and complementing van Hoorn’s electric horns and de Kleer’s own stirring Rother-esque lead guitar amid what is swirling stuff. I can’t really better Jonathan Dean’s words: ‘an ecstatic house-influenced psychedelic jam that succeeds in lifting me into orbit every time I hear it.’ If ‘Marz Attacks’ is the atmospheric prelude, this is the full-on Neu!-meets-Detroit techno motherlode. Its hypnotic power even reminded me somewhat of Steve Reich’s mesmerising minimalism. And it all ends with the “SING WHILE YOU MAY” sample. Swirling. Sterling. Storming. 13. Minutes.

This is another 2000s Dots album which, while not vying with the Asylums or Marias, picks up immeasurably. This has to be one of the releases with the fewest words or phonemes uttered by Edward Ka-Spel and it reveals a band on sterling form, on the whole. While the production is occasionally thin and a few tracks pass me by, this evolves into an irresistibly spacey trip. Clearly, the Dots are aiming for, and succeeding achieving, their own equivalents to Peter Hammill’s mammoth ambient antechamber ‘Gog and Magog (In Bromine Chambers)’ (1974), which I know is a Ka-Spel favourite. Overall, while All the King’s Men is not top tier Dots, it has some outright delights.

Adam: I can’t be alone in filtering most of the media I consume now in relation to the genocide being perpetrated in Gaza. Like many people, I’ve gone to a couple of protests, donated to Médecins Sans Frontières and tried to avoid fence-sitting in conversation with liberal friends. Why haven’t I (and others) here in the UK done more? Honestly, I think after the defeat of Corbyn, the continued failures of the environmental movement, Covid lockdowns, fifteen years of auterity and a purging of socialists from the Labour Party, etc. we feel tired and useless. Having the time and space to feel like this is, of course, an immensely privileged position to be in (I’d much rather feel listless and alienated in a safe house, with warm clothing, food and my family members than the alternative). It has also left me seemingly unable to draw or write creatively and indifferent to much of the collossal amount of media available at my fingertips. For instance, I’m stuck half-way through Nathan Fielder’s The Curse (2023–2024) because watching two gentrifiers force a local population out of their homes fills me with a sense of dread and sorrow where there might have wry amusement and cringing laughter

As such, my feeling of detachment from All the King’s Men and my general inability to connect with the album emotionally may be due more to my currently low-level anhedonia than any qualities of the music itself. However, even taking this in consideration, I still believe that All the King’s Horses is the more emotionally accessible album of the pair, the Kid A (2000) to All the King’s Men‘s Amnesiac (2001). There is a similar sense of the tracks on Side A of King’s Men having been taken from the cutting room floor. ‘Cross of Fire’ promises an industrial soundscape, but never gains momentum, with Ka-Spel’s vocals starting the quietest in the mix I think they’ve ever been. ‘The Warden’ continues the cross imagery, matched to the kind of stentorian gothic organ we heard back on Hallway of the Gods (1997). However, the lyrics are too abstracted to sustain any sense of the titular Warden as the kind of persecutory character listeners encountered on Asylum (1985).

‘Touched By the Midnight Sun’ and ‘Rash’ are both gloomily muted. War shuffles into view, a recurring lexical field. Ka-Spel numbly sings “Cue tympanies a fanfare/ We wore black bands on our arms/ The army fired once”. This imagery helps me to contextualise lines from ‘Warden’ that I had assumed to be targeted against religious fundamentalism, “A head crack in the back yard/ Cross of air, in line”. A church warden is responsible for the items required for Divine Service; air raid wardens gave the message of danger from enemy forces. Does the former kind of warden necessarily lead to the existence of the latter? Or are these ultimately the same job? While abstract, often fragmentary, Ka-Spel’s lyrics on Side A of All the King’s Men seem to be concerned with the way in which ideologies (religious, national and otherwise) ensure persecution and suffering. On The Tower (1984) and Island of Jewels (1987) there was a youthful rage behind these observations, which is here replaced by a defeated and worldweary cynicism. In fact, the resigned numbness of the first half of the album matches my own current feelings, helping me appreciate the honesty of Ka-Spel’s approach.

There are subdued musical flourishes on ‘The Day Before It Happened’, with some keyboard trills that sound like Rachmaninoff tinkering on a music hall piano. Ka-Spel’s vocals are soft and solicitous, tinged with irony. The Silverman’s electronic drones and buzzes are warm and tactile. There is a careful compositional balance between sweetness and sickliness i.e. all the ingredients for a classic Dots track like ‘The More It Changes’ (1988) or ‘Golden Dawn’ (1985). Lyrically I think Tom is spot-on when he writes that it “feels like a bridge between the Dots’ early Second Cold War dread of nuclear war and the subsequent events in Iraq”. Perhaps it makes sense therefore that musically it seems backwards looking, verging on pastiche. Or maybe I only feel that way because the track that follows is called ‘Brighter Now’ and is very clearly intentionally in the style of the early 1980s period of the Dots… In fact, it //is// a cover of the track that appeared right back on Chemical Playschool 1 & 2 (1981) which we reviewed over a decade ago back when I was in my early 20s!! While the Dots have often returned to old material in their live shows, or else have sampled and remixed old tracks on their albums, it is unusual for them to outright cover one of their own songs like this. The audio production is kept intentionally muffled, as though the original track has been summoned to play on a ghostly gramophone (though you can tell that it is the current batch of musicians – de Kleer, van Hoorn and Steeg – performing). The themes of the past – nationalism; religious fundamentalism; war – replay on loop, superficially updated for a new century… why not the music too?

‘Marz Attacks’ layers de Kleer’s guitar feedback to gloaming, majestic ends – dark clouds rolling in. The title immediately makes me think of the ludicrous Tim Burton sci-fi horror pastiche from 1996, though I suspect Ka-Spel and Phil Knight much prefer the original trading cards! Personally I wish the track just continued into the instrumental Side B of the album, but instead we have a grimly whimsical ditty in the form of ‘Sabres at Dawn’. I love a sardonic carnival waltz, but they just arent the same without Patrick Q. Wright on violin!

If All the King’s Men only consisted of the above collection of songs I would place it near the bottom in my personal ranking of Dots albums HOWEVER the following two almost entirely instrumental tracks ‘All the King’s Men’ and ‘The Brightest Star’ are phenomenal examples of collagist space rock that fulfill the promise made by Chemical Playschool Volumes 11,12 & 13 (2001) and then some! While one could (uncharitably) argue that this represents a turning away from politics in favour of a psychedelic innerspace, the Dots have always been consistent in portraying the interior realm as a parallel polis to which escape is sometimes necessary. At the very least, the human animal when faced with relentless stress requires escapism into continue functioning – and being lost in contemplative revelry is surely preferable to allowing oneself to be bombarded by propagandistic Marvel-Disney-metaverse spectacle or the kind of orange-teal self-serious cinematic pap and torture porn that clogged up the multiplexes in the early 2000s.

Fans of 1968–1972 Pink Floyd or Ozric Tentacles will savour much of ‘All the King’s Men’. ‘The Brightest Star’ is arguably even stronger, the experience of which is like being part of a hydraulic-cum-cybernetic network as energy currents flood through your transmogrified form! Perhaps it is the sound of Artaud’s fabled body without organs emerging into being! Otherwise, it put me in mind of the terrible, part-organic part-machine at the heart of industrial capitalism that you ascend into at the end of the poorly understood, remarkable survival horror game Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs (2013)… or, to volley another obscure cultural reference point, the grotesque transformation into battle saints in the weird-fiction podcast The Silt Verses (2021–2024).

As it happens, I wrote an article earlier this year about listening to The Silt Verses in the wake of the atrocities being committed in Gaza. There are still pieces of fiction, art and artists that I’m finding worthwhile to engage with… thankfully the Dots are one of them. Let’s sing while we may.