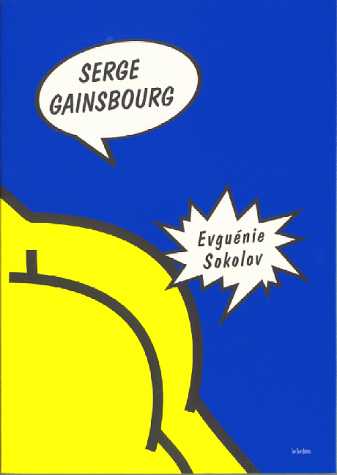

When I bought a copy of Evguénie Sokolov by Serge Gainsbourg, I thought it was, in fact, Serge Gainsbourg by Evguénie Sokolov. I had no idea that Gainsbourg had written a novella — I just figured the slim volume was a collection of essays about the man; this assumption was boosted by a long introduction by Bart Plantenga and an afterword by Russell Mael of Sparks. (As a fan of both Gainsbourg and Sparks, if I didn’t feel like I had to buy it before, that afterword would seal the deal.) It was only after I started reading the introduction that I realized what I had.

What I had was a book about a guy who farted a lot. Rather, a very well-written book about a guy who farted a lot. I suppose the cover art — a pop-art styled, giant yellow ass — should have tipped me off that this was going to be the subject matter, but, well, honestly, a giant yellow ass is a perfectly apt cover for the book of essays about Gainsbourg I was expecting. It IS Gainsbourg, after all.

The titular character is a man whose life seems to have some things in common with Serge Gainsbourg — both are Russian Jews living in France, both have an interest in comics, and both seem to have a pretty big ego. (The introductory line to the novel is “The mask falls, the man remains, and the hero fades away.”) But while Gainsbourg went into music (and presumably didn’t constantly fart), Sokolov went into visual art — making “gasograms”, jagged lines made on paper as he farts while sitting on a spring-loaded bicycle seat. (Gainsbourg, similarly, did a song entitled “Evguénie Sokolov”, which was made up of fart noises.)

Evguénie Sokolov is a short novella — barely 50 pages with large type and margins — although much longer and it’d probably end up overstaying its welcome. While it is basically one joke, it’s a pretty good one — written with purple prose, and, oddly enough, a rather apt metaphor for creating art and the fame that can come with it. Sokolov is a reluctant celebrity — mostly due to embarrassment over his ailment-slash-muse — and avoids the spotlight when he can, but not always. He’s also destroyed by his art (later in the story, in addition to the gasograms, he takes prints of his bleeding hemorrhoids) — where he may have been able to been saved, he wasn’t truly able, as creating art was what he must do.

Sokolov, like Gainsbourg, isn’t a completely likable character. He’s arrogant, he has an affair with a pre-teen girl, and he’s pretentious. (He also farts all the time and eats decomposing meat to help make more and thunderous farts which smell like death.) But that’s what makes him interesting — if Sokolov were a poor, unloved but kind martyr, what fun would that be?

The one problem with the book is that the editing is terrible. The text is riddled with errors — including a repeated line, misspellings, obvious spell-check errors (for example, in the introduction, Gainsbourg is described as having a series of “deadened jobs” rather than “dead end”), and other assorted typos. (For example, the Whitney Houston incident is described as Serge Gainsbourg saying the infamous “I want to fuck you” twice in French — rather than correcting the host by repeating the phrase in English so Houston would know precisely what he meant.) Still — the publisher, TamTam, is, according to the first page, a one-man operation, so the errors can be forgiven somewhat. That said, it would have been better if the editor and publisher had someone else take another pass at it. Regardless — it’s a great book and a must for Gainsbourg fans.