“Sputnik 2 was not designed to be retrievable, and Laika had always been intended to die.”

True story: the tale of Laika, the world’s first space dog sent up on the Soviet Union’s Sputnik 2, has always sent me into gales of uncontrollable tears. It torments me that she was used by people she trusted as a political pawn for a government obsessed with being better than another government. Granted, America had its share of its own horrific tragedies in the quest to beat the USSR in the “space race” (Apollo 1, anyone?), but the story of Laika affected me the most since she most likely blindly trusted the people who forced her into hardcore training, and into a doomed space mission. She was a dog, after all.

The true story of Laika wasn’t released to the world until a few years ago. To make a very long story short, Laika was the first living specimen sent up into space. She was launched into history on November 3, 1957 on the USSR’s Sputnik 2 capsule. However, the capsule was not meant to be retrieved, and the Moscow mutt was never meant to survive. Her last meal (meant to be fed to her on the last day of her mission) was laced with poison so she would die “humanely” (if such a thing could have happened). Her fate turned out to be even worse than what was scripted by the USSR’s mission controllers: her capsule overheated, and she died within 5 to 7 hours of the launch.

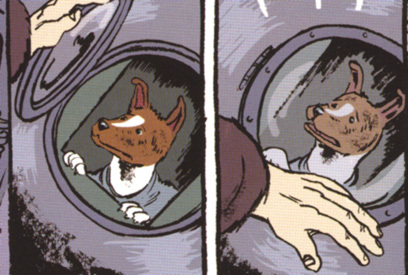

In 2007, artist Nick Abadzis released a graphic novel called Laika, which tells the story of Laika’s short, doomed life in a way which hits the reader right in the heart. The story is told through three perspectives: Soviet scientist Sergei Korolev, dog handler Yelena Dubrovsky, and Laika herself. The part which really affected me about the book was how I felt like I was in the dog’s brain while reading the section from her perspective. Laika endures a depressing youth when she is mistreated by former owners, and trusts Dubrovsky’s character implicitly when the dog handler says, “You can trust me.” We see how Laika’s heart swells when Yelena calls her a “good dog.” Laika’s only desire in the world is to be loved by humans; one can see the absolute terror on her face as she is trapped in a space capsule by these same humans who “loved” her. However, Laika’s ultimate dream is realized even in her most terrifying moment: she has always dreamed about flying, and now she is flying in space, unfettered by the political motives of human beings and from all cares in the world.

The book is very beautifully illustrated, and is filled with pathos and heartbreak over the fate of the dog. Perhaps the most poignant scene of the book is when one of the scientists takes Laika home with him before the launch so she has an opportunity to be a “normal” dog; she plays with the scientist’s children, not knowing the fate she is about to meet. Ultimately, one takes away the feeling that governments don’t always know what they are doing, and political struggles force governments to make innocent beings suffer (and sometimes die). Scientist Oleg Gazenko, one of the scientists who worked in the Sputnik program, stated about Laika, “Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it…we did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog.” This book makes me mourn immensely over the loss of this guileless creature who wanted nothing except approval from the very people who orchestrated her death.

Upon Laika’s death, I can only hope that in heaven she asserted herself as the world’s first space heroine, and I hope she is having some fun running around and snacking on some excellent dog treats. Near Moscow’s Military Institute, a statue of Laika standing proudly on top of a rocket has been erected, sealing her legacy as an intrepid traveler and a damn good dog.

[

[