When most people think of the vocoder, they think of the

robot voice on the Kraftwerk records…. or perhaps the mangling that

Cher’s voice goes through on “Believe” or

T-Pain’s voice on any T-Pain record. (That last one’s not actually a vocoder, though; that’s

Auto-Tune, which is different.) But most people don’t know that the vocoder was originally designed as a secure way for heads of state to talk to each other during

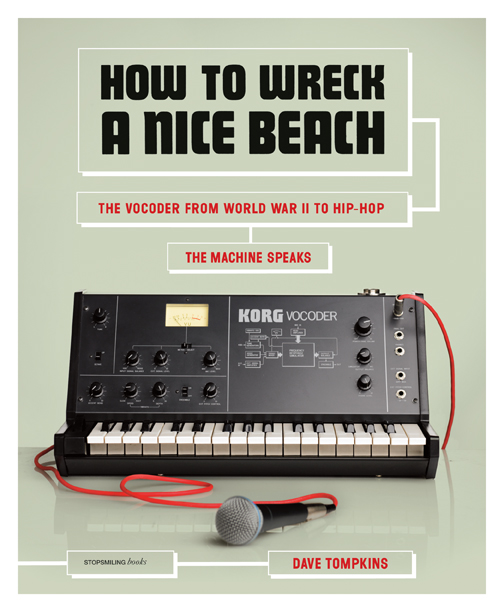

World War II. Dave Tompkins’ new book

How To Wreck A Nice Beach goes through the history of the vocoder, from its militaristic roots to its more fun applications in music, radio dramas and film.

The first vocoders filled up rooms and combined speech with noise coming from disposable records played from the center out — a bit different than the ones that most people think of, being either a small rack-mount box or a mic attached to the top of a Korg synth. Tompkins interviews many of the folks either involved with these original vocoders or those who worked with those involved. (After all, a lot of the original inventors aren’t alive anymore, sadly.) There’re also detours into the original Auto-Tunes, those devices that people could think were vocoders but not — like the Sonovox, a speaker that goes against the speakers throat to make all sorts of noises (for example, the old Lifebuoy soap ads with the “BBBBBBBBBB-OOOOOOOOOO” foghorn), the Talk Box, which worked similarly only with a vibrating tube to be placed in the mouth to make sounds talk (think Frampton’s “Do You Feel Like We Do” or one of the masters of the Talk Box,

Roger Troutman), often at the cost of teeth, and also everyone’s first voice-manipulator, the electric fan.

Tompkins interviews a lot of people — including, remarkably, Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk about the gear that Kraftwerk used, particularly in the earlier days. There’re also interviews with lots of people who had early success with vocoder records like Michael Jonzun from the Jonzun Crew (“Pack Jam (Look Out for the OVC)”), Bill Sebastian who worked with Jonzun and Sun Ra (and was the inventor of the real OVC), Rik Davis of Cybotron (“Clear”), Man Parrish and Afrika Bambaataa, just to name a few.

Unfortunately, sometimes Tompkins attempts to write for style rather than clarity, and those particular sentences tend to require a few reads — not for enjoyment but to suss out his point. Also, the penultimate chapter is about Rammellzee, which has very little to do with the vocoder. Rammellzee sometimes used it, but the thrust of the chapter seems to be about how awesome (and seemingly certifiably insane) Rammellzee is; for folks who aren’t familiar with his work, it just comes off as an irrelevant sidebar, one that oddly doesn’t make its subject come off as well as the author seems to hope.

Still — it IS beautifully put together with lots of full-color and black and white photographs of the major players in the history of the vocoder, important record sleeves, and wonderful illustrations by Kevin Christie opening each chapter. The book was clearly assembled with love, and the secrets revealed about this wonderful instrument are incredibly interesting — it’s definitely a must-read for any gear head, electronica or Hip Hop fan, or military technology enthusiast.