A LIST POST!

Jan Švankmajer does not like to be known as an animator. After all, while mostly known here in Britain (and Western Europe more generally) for startling, animated shorts like Dimensions of Dialogue (Možnosti dialogu, 1982) or Food (Jídlo, 1992) or from animated gifs of scissor-wielding white rabbits and denture-clacking caterpillars on Twitter, Tumblr and Instagram from his creepy feature-length adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Něco z Alenky, 1988), he’s also a prolific maker of sculptures, collages and erotic tactile art. However, Švankmajer doesn’t even like being referred to as an artist! As a member of the Czech Surrealist Group he does not see himself as an individual making art, but as engaged in a communal practice of being-in-the-world as a Surrealist first and foremost.

Considering this, it is unarguably perverse to consider Švankmajer not only exclusively as a filmmaker, but as a horror filmmaker at that! It would be easy to assume that the rigorous, semi-intuitive form of free-associative creation practiced by Surrealists would be incompatible with a genre that can be so predictable in its rules and (enjoyably) eye-rolling in its clichés that it is possible to enjoy partial parodies like Scream (1996) or The Cabin in the Woods (2011) without having even seen that many horror films! Of course, there are certain directors of horror like David Lynch (Lost Highway, 1997), Dario Argento (Phenomena, 1985) or Alejandro Jodorowsky (Santa Sangre, 1989) whose works might be considered surrealist in the colloquial sense of being weird and dream-like, but they aren’t “capital S” Surrealists in the sense of being members of a formal group or movement.

However, even considered as an art historical movement, Surrealism never cared about preserving the boundaries of high and low culture and, in fact, many of the most renowned Surrealists clearly loved horror! Antonin Artaud (who either left or was thrown out of the original French group by founder André Breton in 1927, depending upon who you believe) once gave a lecture entitled ‘Theatre and the Plague’ in which, as he gave the lecture, he pretended to succumb to the successive effects of the Bubonic Plague until he was rolling and writhing about the stage. In some performances of his so-called ‘Theatre of Cruelty’ audiences would be spattered with pig’s blood. Salvador Dalí’s and Luis Buñuel’s short film An Andalusian Dog (Un Chien Andalou, 1929) notoriously begins with a woman’s eyeball apparently being sliced in half with a razor blade and later contains the image of black ants swarming out from a hole in a hand. The Czech Surrealist Group’s (the oldest still-surviving Surrealist Group in existence, dating back to 1934) periodical magazine Analogon has even had a special issue upon the subject of fear and nightmares. Surely, it is only natural that an artistic practice that involves the artist plumbing the murky depths of their unconscious and childhood memories should bring to the surface material that would not feel out of place within a horror film.

For me it makes a certain intuitive sense to consider Švankmajer’s film work as horror since that it how I first experienced it late night on Channel 4 around the age of sixteen. Back when the channel was still known for its innovative programming, I used to stay up on Friday and Saturday nights into the small hours of the morning, alighting upon dark cult comedies like Chris Morris’ Jam (2000) and discovering unsettling horror films like Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) as I drifted in and out of consciousness. It was in this state that I first chanced upon Švankmajer’s cannibalistic fairytale horror Little Otik (2000); prompting me to lay my hands on everything I could get hold of by the Czech visionary on VHS at the point at which it was cheap to do so due to the format’s replacement by DVD. As for why Channel 4 was screening Švankmajer, it was due to Film4’s funding of his work at the end of the 20th century. After the so-called Velvet Revolution which heralded the end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, filmmakers and artists like Švankmajer were, for the first time in their lives, in the position of having to find private funding for their work. Britain’s Channel 4, with its remit to help bring innovative and original content to screens, stepped in to co-produce Alice and, later, Little Otik.

I am not the first writer to consider Švankmajer’s work as horror cinema. Paul Wells’ The Horror Genre: From Beelzebub to Blair Witch (2001), Steven Schneider and Tony Williams’ Horror International (2005), Bartłomiej Paszylk’s The Pleasure and Pain of Cult Horror Films (2009) and Kim Newman’s Nightmare Movies (2011) all contain a section on Švankmajer and some of his films. Taste of Cinema, Cartoon Brew, Dazed, Squeezed Media and The Prague Reporter are just a few of the online magazines to list at least one Švankmajer short or feature as a horror film.

Brigid Cherry, in the late lamented Kinoeye journal (2:1, 2002), has noted that while Švankmajer’s films “may not be straight horror”, “they draw on Gothic literary sources and have a definite appeal to horror film fans”.[1] Also in Kinoeye (2:1, 2002), Jan Uhde has classified Švankmajer’s 1970 film of the Sedlec Ossuary in Kostnice a “horror documentary”;[2] while Paul Wells (2:16, 2002) has argued that Švankmajer uses what he calls “agit-scare” tactics in order to unsettle the audience’s commonplace assumptions about the nature of reality and civilisation.[3] Finally, even Švankmajer himself has appeared on-screen in a preface to his film Lunacy (Šílení, 2005) describing what is to come as a “horror film, with all the degeneracy peculiar to that genre”.

František Dryje (in Peter Hames, The Cinema of Jan Svankmajer: Dark Alchemy, 2008), another member of the Czech Surrealist Group and editor-in-chief of Analogon, has divided several of Švankmajer’s films into four different sub-categories of the gothic: Classic Gothic, Fantastic Gothic, Realistic Gothic and Burlesque Gothic (p.175). Taking from Dryje’s lead, I will now divide up some dozen of Švankmajer’s films into four different horror categories, linked by a common theme or motif – what we might call each film’s “animating anxiety”:

-

Gothic Horror

-

Puppet Horror

-

Food Horror

-

Existential Horror

For each I will also include a few honourable mentions, as well as ascribing each film a ‘horror rating’. This rating does not indicate my personal ranking of the quality of the work, but simply the degree to which it succeeds generically as a piece of horror cinema. Where possible, links will be provided.

Gothic Horror

From Marx Ernst’s 1934 collage novel A Week of Kindness (Une Semaine De Bonté) in which beastly cloaked figures take from Victorian lithographs engage in impenetrable but doubtlessly diabolical crimes, to the preponderance of crumbling ancestral castles in the writings of André Breton and Artaud, Surrealism has always had a close affinity with and appreciation for the gothic.[4] Within a more specifically Bohemian frame of reference, the most famous horror film of the Czech New Wave is doubtlessly Jaromil Jireš’s Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Valerie a týden divů, 1970), which was adapted from a queasily Freudian gothic fairytale by Vítězslav Nezval, co-founder of the Surrealist movement in Czechoslovakia. After all, both Surrealism and the Gothic take a more than morbid curiosity in the phantasms and dark fantasies that lurk under the veneer of civilisation…

The Ossuary (1970)

The Sedlec Ossuary is a Roman Catholic chapel located beneath the Cemetery Church of All Saints in a suburb of Kutná Hora in the Czech Republic. It is largely furnished in the burlesque style with the bones of some 40,000 to 70,000 skeletons, many of those from victims of the Black Death. Bones decoratively line the walls, have been assembled into a macabre coat of arms, and even comprise a monstrous eight-pronged candelabra.

Švankmajer’s documentary of the Sedlec Ossuary is a frenzied montage shot in disorientating extreme close-ups. The 10-mention short was originally over-dubbed with the narration of an actual tour guide, their banal accounting of events rendered uncanny through contrast with the visual phantasmagoria of human ruination. After censorship, Švankmajer replaced the soundtrack with a jazz freak-out from Zdeněk Liška, making the results more feverish, but less acerbic.

While the sheer scale of human death on display and the whimsical treatment thereof is bracing, even numbing, the restless nature of the camerawork means that the viewer never really gets a sense of the location and its atmosphere. Both soundtracks diffuse the horror through black humour.

Horror rating = 2/10

Castle of Otranto (1977)

This is, in a sense, the most traditionally gothic of Švankmajer’s films since it is adapted from The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole, arguably the original gothic novel. However, Švankmajer takes a curious approach to the material, filming it as a faux-documentary with animated inserts of paper cut-outs from lithographic illustrations. The effect is highly distancing, emphasising the absurd stylisations of Walpole’s novel to a point of complete estrangement.

The film is set amongst the ruins of a castle and features a gigantic several head, but the impact is closer to Monty Python than outright horror (which makes sense, since Švankmajer has been an avowed influence upon Terry Gilliam). Still, in terms of the location and motifs alone, this could be classified as gothic horror… even though it certainly isn’t scary, but dryly amusing.

Horror rating = 3/10

The Fall of the House of Usher (1980)

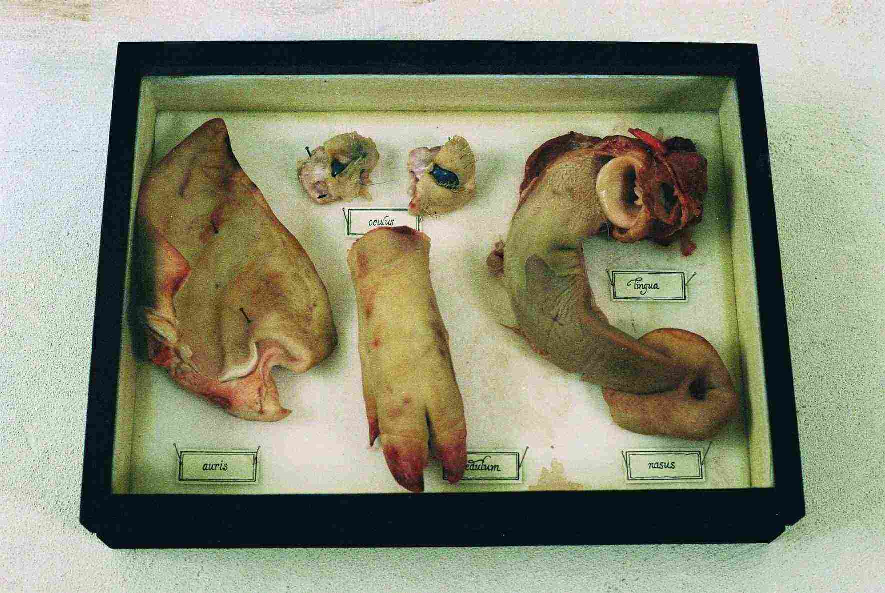

Arguably Walpole’s source novel was always too fantastical to make for effective horror – events and the actions of characters often seem unmotivated and there is a casual disregard for narrative logic. By contrast, Edgar Allan Poe, a much later author writing at the point at which the gothic had undergone some psychological development as a genre, often adapts well to horror – from the 1928 jagged expressionism of Watson’s and Webber’s silent Usher short, to the technicolour nightmares of Roger Corman. Švankmajer produced his adaptation of Usher after an enforced hiatus from filmmaking in which he had focused his attentions upon tactile experimentation. If you’ve ever played the Halloween game in which you have to feel various slimy or bristly objects within a bag while blindfolded… well, most of his experiments were basically a more sophisticated variation on that!

As such, Švankmajer is more interested here in the texture of the objects of Usher’s house (and the house itself) than he is in any of the story’s characters… to such a degree, in fact, that the film doesn’t actually feature any human actors at all! Poe’s tale is narrated as the camera traces the surfaces of various decayed and dilapidated objects within the house while, outside, mud churns in primitive stop-motion animation.

Mark Fisher in The Weird and the Eerie (2016) describes “the Eerie” as absence where presence is expected. Here the absence of human actors is unsettling as it means we start to anthropomorphise the objects on screen instead. We half expect an old wooden chair to sprout lips and eyes and talk to us! In a different Švankmajer film, this might have happened… but here everything remains haunted, on the verge of animism, without quite coming to life. As such, the film unsettles deliciously without quite jolting you awake. Švankmajer’s other Poe adaptation is just that little bit scarier…

Horror rating = 5/10

The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope (1983)

As a committed pessimist, hope in Švankmajer’s films only exists to be dashed, and the hope in the title of this dank and claustrophobic adaptation of one of Poe’s most sensory tales is very fleeting indeed. While Eva Švankmajerová’s paintings recall the gnarliest of medieval manuscripts, there is less weeping and gnashing of teeth here than one might expect. In fact, it is the artisanal, hand-crafted, pasteboard quality to the torture equipment that appals. Men are quite capable of creating their own secular Hell for other humans here on Earth.

The soundtrack alone is a charnel house of horrors, a soundscape of close-mic’d Foley recordings of abject creakings and groanings. Without the music by Zdeněk Liška which so characterised Švankmajer’s 1960s output, the film lacks the whirligig frenzied energy one tends to associate with the director – the effect is somnambulistic. It is a film told in hushed horrified whispers and screaming from afar.

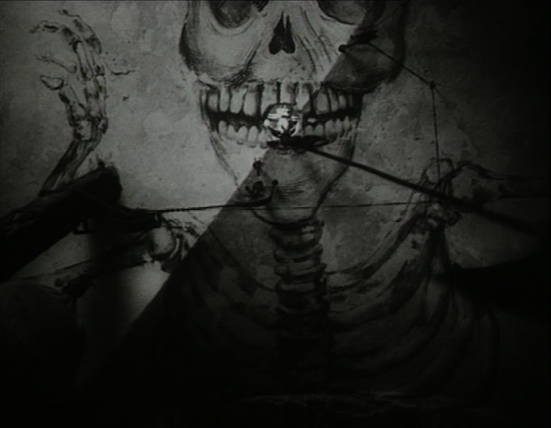

The fact that the film plays out entirely in point-of-view shots gives it a rare emotional intimacy generally lacking in Švankmajer’s work, which tends to bring textures up very close, but keep human sentient at a distance. In place of his typical cynical, black humour, there is a deep pessimism here, tempered with pity. In the screenshot above, the poor doomed protagonist looks up at the fresco of a skeleton on the ceiling above him from which a scythe makes its inexorable journey ever closer…

Horror rating = 6/10

Honourable Mentions

Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasy in G minor (1965)

This is an abstract tone poem told through dilapidated objects and coarse textures. The effect is not scary or horrifying, but the aesthetics are gothic. A minor, but intriguing work.

Puppet Horror

The Czech Republic has had puppet plays since at least the 19th century, when wandering German puppeteers crossed the border into Bohemia to perform regional variants of the Faust myth, Don Juan and Punch and Judy to audiences of both adults and children. Švankmajer’s university training was in puppet theatre and while he clearly has a certain nostalgia for traditional Czech puppet designs, he is also far from unaware of their uncanny, even abject qualities. Puppets in Švankmajer’s films always look like they’ve taken some hard knocks. They tend to look moth-eaten and shop-worn. However, if anything, this seems to make their vitalist energies thrum all the harder! And surely, after years of being danced about on the ends of strings or uncomfortably manipulated by a puppeteer’s hand, you can’t begrudge them their occasional bouts of violence…

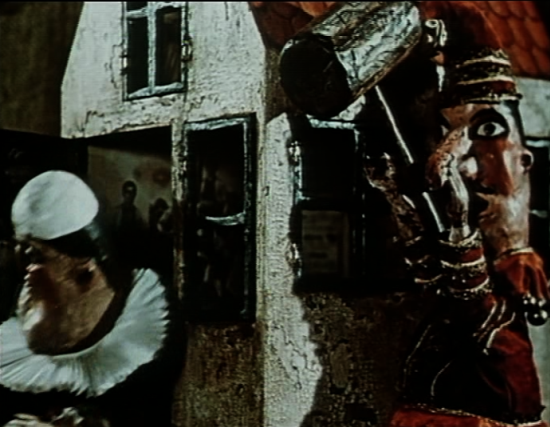

Punch and Judy (1966)

The fact that the alternative title for this film is The Coffin House should give you some indication of its macabre content. Here Punch (Kašpárek in Czech) and another block-headed puppet called Joey haggle and argue over the ownership of an ever-oblivious guinea pig. The juxtaposition of the cold wooden hands upon the warm buzzing flesh (I’ve lived with guinea pigs – they buzz) of the chubby adorable rodent is skin-crawling enough… but the maggot-like grains poured out of the hollowed-head of (a lithograph of) a Victorian lady, fed directly into the guinea pig’s slobbering mouth, take things to another level! Punch and Joey become Itchy and Scratchy-like in their mutual animosity and are soon hammering nails into each other’s faces and bonking one another upon the head with a comically oversized mallet. Really, it’s Zdeněk Liška’s remarkable sound design that provides the unsettling ambience however – all hushed whispering voices and percussive echoes. Startling and faintly unpleasant.

Horror rating = 6/10

Don Juan (1970)

This is easily the longest of Švankmajer’s short films at half-an-hour in length. In some respects, it’s a surprisingly straightforward rendering of the puppet play version of the Don Juan legend… except for the fact that the “puppets” are actually giant horrifying papier-mâché costumes worn by actors moving like creaky marionettes. Even while it is seemingly wooden faces being sliced from heads, the blood is as red as any in a Hammer Horror film, spurting out from holes in the man-sized puppets. The aggressively stilted rendering of the dialogue and the stylisation of the whole affair makes the film distinctly alienating. The violence feels preordained (after all, puppets don’t have free will) and so, numbingly stripped of morality. A bleak vision and probably the closest Švankmajer has come yet to the puppet horror of Thomas Ligotti, though years before the latter published his debut short story collection in 1986.

It’s more of a disquieting rather than an outright scary film. Possibly this is because the puppet people – with their stiff movements and mannered expressions – are deep enough into the uncanny valley that they seem distanced from us rather than relatable. They seem to exist within their own dead world. It’s only when we realise (a la Ligotti) that this world is literally our own that we might start truly feeling horrified.

Horror rating = 6/10

Faust (1994)

Faust retells the story of the fabled scholar-magus who makes a pact with the devil as the story of an everyday schmuck who gets in over his head after being handed a leaflet in the street directing him to a puppet theatre. The horror here derives largely from the juxtaposition between the banality of contemporary Prague with its shopping districts and tourism precincts and the occult superstitions of the Faustus myth (still sold in Czechia as real local history, such as in the Museum of Folklaw in Prague).

In many ways, Švankmajer neuters the horror of his film with his use of Brechtian distancing effects. Almost every time we see something strange and supernatural, it is then revealed as a cheap parlour trick. The necromancers Valdes and Cornelias have pupil-less white staring eyes? … They had just capped white shells over their eyes! A burning carriage rattles down the cobblestones like a dark and evil portent … And there comes the health & safety guard with a fire extinguisher to put it out!

However, this disenchantment of the world holds its old horrors. With no real magical powers gained, Faust (who could be standing in here for really any citizen of a newly consumer post-communist society) has sold his soul for a handful of dust. That critique was always there is Christopher Marlowe’s original play, but could get lost amongst the hijinks of the 17th century Faustus being able to turn invisible and smack around the Pope etc. Here Faust has made the same devil’s gambit as we make every day when we buy – say – cashew nuts that required workers to terribly burn their hands when harvesting them; or an iPhone made by suicidally-overworked labourers in China; or a chocolate bar with child slave labour baked into it… etc. etc. etc. laying down inauspicious brick after brick until we have paved our own path all the way to Hell.

Horror rating = 7/10

Honourable Mentions

The Last Trick (1964)

Two puppet-man magicians engage in a battle royale on stage in a contest that makes The Prestige look peaceable. The film contains the brilliantly Surrealist motif of a black beetle that crawls its way through the insides of the magicians and is eventually squashed. An auspicious beginning!

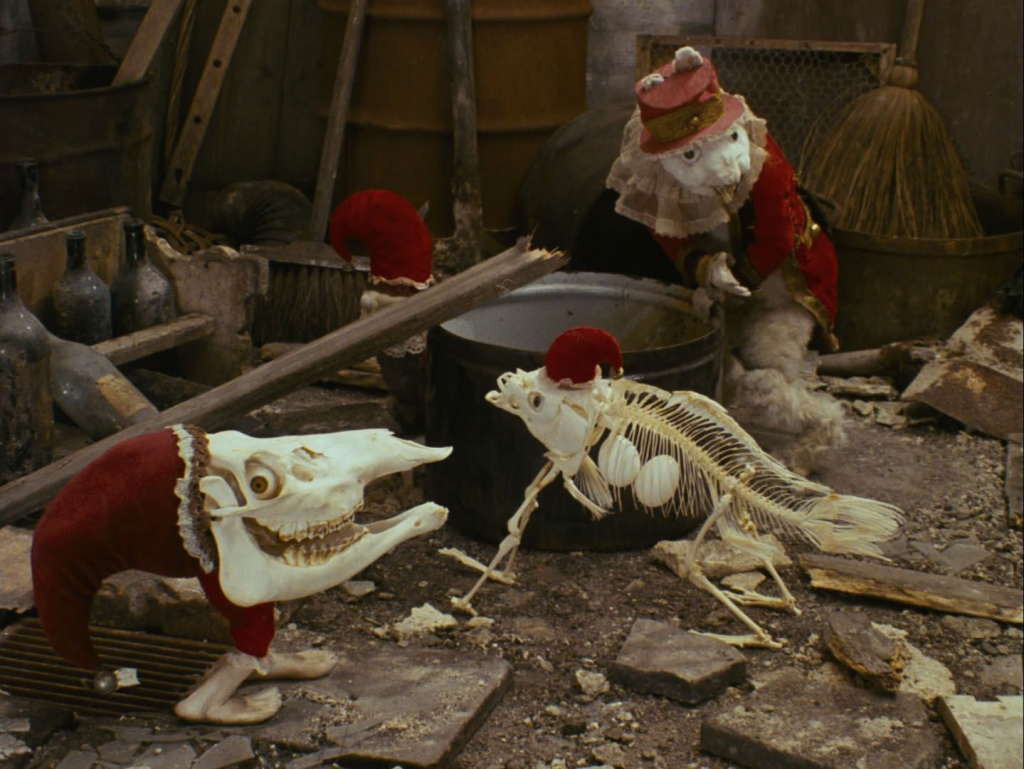

Jabberwocky (1971)

Švankmajer’s aggressively inventive visualisation of the stages of a child’s psychosexual development, containing a lot of visual innuendo and scenes of delicate porcelain dolls committing cannibalism. Wears its Freudianism on its blood-speckled lacy sleeve. Cheerily perverse Victoriana of the highest order and a hugely memorable exhibition of infantile aggression!

Food/ Fairytale Horror

Fairytales are all about the basic stuff of human existence – avoiding death; having sex; eating food. Before being Disneyfied (and even watered down by collectors, transcribers and translators like the Brothers Grim and Charles Perraut as they republished later editions of their own collections) fairytales were grim fables of life lived in poverty. Švankmajer grew up in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia and then came of age under Stalinism. Life was tough. Švankmajer has recalled that as a child with an eating disorder he was taken away to a Soviet eating camp for children, where he was force fed. It is not surprising therefore that Švankmajer’s films with child protagonists tend to focus upon the icky horrors of consumption. Food in these films is lumpy, mushy, rancid, stinking, rancid, cold potatoes, broth with nails, jam hiding pins, even human flesh… yet you still have to eat it.

Down to the Cellar (1983)

A dirty, thin-faced little girl is forced by her parents to collect potatoes from the dark cellar. Things lurk down there. A black cat. People. In a way, Down to the Cellar might be Švankmajer’s closest release to a traditional horror film, recalling nothing so much as Wes Craven’s The People Under the Stairs (1991). However, the bogeymen here are figures of abject poverty just as much as our child protagonist… indeed, they might even mean well. The desiccated old lady offering cakes of coal… maybe she’s not so much the witch from ‘Hansel and Gretel’ as the grandma from ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. The old man offering a place in his bed of dirt might not have sinister intentions… best not to find out. The film illustrates the dangers of childhood starkly from a child’s perspective.

The stop-motion here is all the more vivid for how sparingly it’s used.

Švankmajer has recalled how the film has autobiographical origins. As a child he had to go down to the cellar to face potatoes and he dreaded it. Maybe these are some of the horrors he faced, caught between the imaginary and the viscerally real.

Horror rating = 8/10

Alice (1988)

Švankmajer’s adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s children’s classic Alice in Wonderland is more like a child’s fever dream of the book than an adaptation in any traditional sense.[5] While Carroll’s vision was a strange-bucolic playroom of upended logic and playful punnery, Švankmajer’s Wonderland is dank, dirty, down-at-heel and far more invested in the unpredictable transformations of the material realm, than in language or mathematics. Perversely, while Tenniel’s iconic illustrations for Carroll’s work are often suggestive of scenes from an English country garden, Švankmajer chooses to stage his Alice within cramped and dusty interiors. The film is a phantasmagoria of darning needles and loose buttons and dead leaves. The White Rabbit is a mangy, bug-eyed piece of taxidermy with a hole in its stomach that leaks sawdust. The Caterpillar is an old sock with two glass eyes that are sewn over with grey wool when he goes to sleep. The Cheshire Cat does not appear in the film… but you can guarantee that if it had, it would have been represented by a pair of stained dentures!

The sound design is vividly hyperreal here, full of scrabbling and squeaking. Indeed, Alice must be one of the most tactile of Švankmajer’s films. You undergo Alice’s adventures alongside her at child’s eye view, beset by pop-eyed little cadavers and other threatening beasties.

Testimony to the materiality of the film – its groundedness – is the fact that many of its puppets have been exhibited as objects in various exhibitions of Švankmajer’s art. Back in 2013 I was privileged enough to visit such an exhibition at Brighton University and even stood in front of the Red King and Queen (rendered as human-sized playing cards) and spoke aloud to them Alice’s defence in court: “I didn’t do anything… Well… Hardly anything”.

Horror rating = 6/10

Little Otik (2000)

Little Otik (or Otesánek) is an adaptation of a traditional Czech fairytale by Karel Erben. In the story, Otik is hewn from a tree stump that happens to resemble a baby, gifted to a childless woman by her husband as a joke. The joke backfires however when the woman treats the stump as though it were a real baby, wet nursing it to life. Otik’s insatiable appetite leads him to drink litres of milk and broth, and it isn’t long before he has moved onto eating chunks of meat and the family pet. Having gobbled down his mother and father, Otik cannibalises a whole host of people before being eventually stopped by an old lady with her trusty cabbage hoe.

Švankmajer plays the tale surprisingly straight and even interpolates Erben’s original story within the film in the form of paintings by his (late) wife Eva Švankmajerová. His major change is to set the film in the then-modern day of post-communist Prague (as with Faust previously). With the events of the film taking place in a drab apartment block, the fairytale gains a grimy kitchen-sink realism. Otik – driven by selfish desires as much as any baby – is a frightening movie monster, with scrabbly twig fingers that grasp at his human victims’ hair, pulling them towards a slathering pig’s tongue that emerges from a hollow in his wood.

Still, Švankmajer, like many other great directors of strange short films – the Brothers Quay, Michel Gondry, David Firth, Jack Stauber – struggles with the shift to the longer format of feature-length filmmaking. Otik drags at part, involving some slightly dreary sections of narrative exposition. This somewhat undermines the tension of the film, which never quite maintains the pace of its thrilling/gruelling first half-an-hour.

Horror rating = 7/10

Honourable Mentions

Dimensions of Dialogue (1982)

Possibly the most iconic Švankmajer short and the one most film students will know him for. A triptych of severed heads failing to communicate. The first section represents Švankmajer’s most committed celebration of the art of Guiseppe Arcimboldo, with strange composite heads gobbling each other into annihilation. The final section is a wonderfully inventive indictment of utilitarianism, with clay heads playing a game of ‘Rock/ Paper/ Scissors’ with a motley array of consumer objects.

Meat Love (1988)

A one-minute squicky quickie. A blackly humorous tale of lust and death between two hunks of medium-rare steak. Too silly to be really considered horror (you can even see the strings puppeteering the meat marionettes!) but this metaphor for the bloody materialism of human life has a sting in its tale.

Food (1992)

Three allegories for the grim cycles of human consumption and exploitation. A little too schematic to be scary but contains some of the most face-manglingly brilliant stop-motion in Švankmajer’s career. Mouth-watering, eye-popping, genital-gouging good fun!

Existential Horror

What’s it all about? For a people who have spent centuries being invaded and occupied by other countries, it is no wonder that the Czech have often been known for a gloomy, pessimistic sense of humour. The most famous Czech author is Franz Kafka, whose parables often function as allegories for the inherent absurdity and meaningless of human existence. Existentialism as a philosophy asks that humans seek for personal meaning in their lives in the face of this terrible absence. Švankmajer, however, seems typically sceptical that such a project can ever work out well…

The Flat (1968)

A man (Ivan Kraus) is persecuted by the objects of an apartment which seem to have collectively chosen to no longer obey human commands or meet our needs. He is bopped on the nose, his clothes caught up on nails, thunked on the foot by a hard and heavy egg, tricked by a beer glass that reduces itself to the size of a thimble, dunked head-first into a bowl of soup… amongst many other slapstick indignities. The effect is more humorous than horrifying, but the short effectively captures the experience of sensing an alien malevolence in the world of objects. After watching this film, you will never quite trust your household appliances again.

The horror is existential because it captures a fundamental alienation at the heart of human existence – how we are caught up in the world yet estranged from it through our neurotic self-awareness. The film performs an effective critique of anthropocentricism – the assumption that the world is our dominion, which we can order and understand through our rational systems of control. How arrogant and farcical of us.

Horror rating = 4/10

A Quiet Week in the House (1969)

A disquieting and bitter reflection upon the crushed hopes of the Prague Spring. A government agent (Václav Borovicka) peeps through holes in the walls of a dilapidated house where he spies upon phantasmagoric rituals performed by objects/things. These scenes are in vivid colour, with Švankmajer experimenting with exposure times to create a smeary, blurring effect to his usually juddering stop-motion. The animated vignettes are inexplicable and strange, but quietly disturbing. There are possible visual metaphors for censorship and even the Soviet tanks that rolled into Prague to quash the liberalising reforms. The overall impact is one of troubled and troubling perplexity.

This is the closest Švankmajer has come to the style of fellow Czech director Věra Chytilová and, indeed, it is – like Chytilová’s work – arguably more avant-gardist than Surrealist. Švankmajer does not like being grouped in with the Czech New Wave directors, but here formal playfulness seems to serve serious political aims (and specifically Czech ones at that). Maybe it is the lack of universality that makes this one of Švankmajer’s least loved films, but it is one that I have found myself returning to repeatedly, if mainly to puzzle over.

Horror rating = 6/10

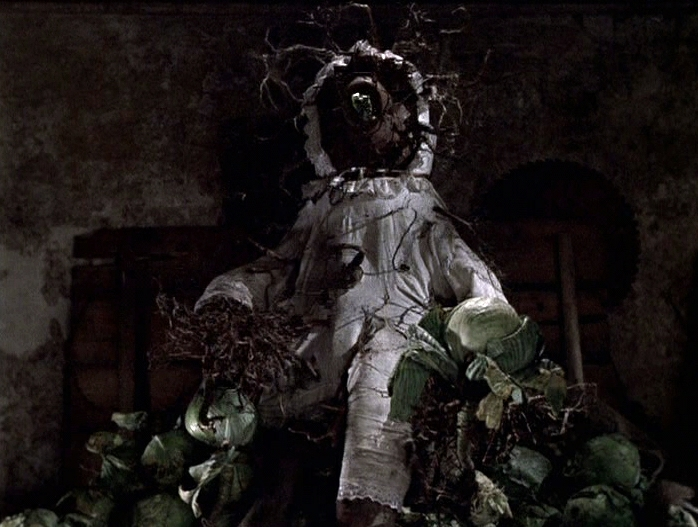

Flora (1989)

Just thirty seconds. A female composite figure, composed of vegetables, fruits and grains, is tied to a dirty hospital bed. Unable to reach a glass of water, she writhes in agony as her body moulders and decays. Just thirty seconds is enough to imprint this indelible nightmare upon your brain forever.

Švankmajer underwent an LSD trial conducted by the Czech military in the spring of 1972. He felt his body and selfhood disintegrating and had to be restrained after attacking a nurse. This short might be allegorising the artist’s experience, but it also functions devastatingly as an allegory for the brief experience of human life in which we are all trapped within our own organic prisons, sentenced to slowly rot and wither.

Horror rating = 8/10

Lunacy (2005)

When I was twelve years old, I stopped eating pigs. In the two decades since, I have vacillated from pescatarianism to vegetarianism to veganism and back again, but I have never and will never return to eating pork. Pigs are too emotionally intelligent, too communal, too perceptive and alive to the world for me to countenance their being killed for either human sustenance or pleasure. As such, the sheer amount of real dead pig flesh in Lunacy throws up a significant barrier to my enjoyment.

But then again, Lunacy is not really a film to be enjoyed. It is a film in which all the world and all the people in it are reduced to flesh. It is primarily inspired by the works and life of the Marquis de Sade and follows his philosophy of moral negation and cruel pleasures. Pigs and humans are eviscerated (in the first instance, literally, in the second instance, spiritually). Even Švankmajer’s characteristic crawling, slavering tongues prompt only a deadened frisson here.

The apparent hero of the film, Jean Berlot (Pavel Liška) is a weakly manipulated fully-grown waif who voluntarily commits himself to an insane asylum. The film’s real “hero” is a man, played by Jan Tříska, who believes himself to be de Sade, engaging in the ritual abuse of others at the asylum. Švankmajer’s preference for the radical freedom represented by this character (even extending to torture and rape) over the suffocating strictures of civilisation imposed by the asylum’s management and staff, reflects his experience of censorship and repression under the Czech Communist regime. It is a provocative position for a humanistic, liberal viewer and is intended to be. Man – if his will is great enough – may choose to do what he wants with pigs (even if these pigs are human men and women). Švankmajer is not being prescriptive here, but describing the nature of the ID. If we find this disturbing or distasteful, it is being this sadistic drive to power exists within us all.

Horror rating = 9/10

Honourable Mentions

Et Cetera (1966)

More darkly funny than scary, but for me it lingers in the mind. Pin-joint puppets demonstrate the absurd cycles of human hubris. Admittedly slight but still undervalued by the critical community. Zdeněk Liška’s mechanical electronic score is about twenty years before its time, sounding weirdly like a demonic Gameboy.

Darkness/Light/Darkness (1989)

A neat little parable about the futility of human existence. I find it a little on the nose, but it contains some of Švankmajer’s most indelible images, such as eyes at the ends of stalk-like fingers – a possible influence upon Del Toro’s design of the Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth – and a clay penis snuffling around on the ground like a dog.

Insects (2018)

Švankmajer’s most recent (and very possibly last) film was disappointing to some, but actually the logical end-point of his career and his most rigorously Surrealist film to date. Švankmajer has always insisted that Surrealism is not an art practice but a creative and collaborative mode of life… as such, the meat of his work is in the process not the product. Crowd-funding (of which I was pleased to be a part) has been a way for Švankmajer to realise this vision on screen. Instead of a static, always finally finished work of art, Insects plays out more like a work-in-progress, a bit loose at the seams and unfinished. This is a deliberate strategy. Out-takes are included in the body of the film, as are interviews with cast and crew. Insects is both an adaptation of the Capek brothers’ play by the same name, but also a film about the making of such a play and then a film about making a film about the making of that play.

The results are a little vertiginous and boring, but such is life.

In conclusion, Švankmajer has never released a film that is wholly horrifying, though Lunacy comes closest. Surveying the artist’s career from the vantage point of the end of his life, it is clear that he has never been a genre filmmaker, existing outside of any traditions expect for Mannerism in his early works and Surrealism in his later. For Švankmajer, Surrealism is a revolutionary mode of being, not just an aesthetic practice.

I do, however, hold out a little hope that we might be blessed with one final short film from the master. If so, it may be the most horrifying of them all.

—

Adam Whybray lectures in film at the University of Suffolk. His book The Art of Czech Animation: A History of Political Dissent and Allegory was published by Bloomsbury in 2020. You might know him best from The Legendary Pink Dots Project which is now also a podcast.

You can read an interview about the book here:

https://english.radio.cz/political-dissent-czech-animation-jiri-trnkas-cybernetic-grandma-jan-svankmajers-8690437

[1] http://www.kinoeye.org/02/01/cherry01.php

[2] https://www.kinoeye.org/02/01/uhde01.php

[3] https://www.kinoeye.org/02/16/wells16.php

[4] https://www.routledge.com/Surrealism-and-the-Gothic-Castles-of-the-Interior/Matheson/p/book/9781409432746

[5] Appropriately, the Czech title translates to “Something from Alice”.