Image via Wikipedia

The Comic Book Industry, and I, Grow Up by D.J. Sylvis

For comic book fans, last week signalled the end of an era as the last few publishers abandoned the Comics Code Authority. It was actually an era that had ended for all intents and purposes anyway – DC was only submitting its kiddie comics for review, and if anyone really believes that Archie Comics were ever really pushing the boundaries of acceptability, maybe they’re the ones stuck in the fifties.

But for those of us who grew up with those little stamps marking the corner of all our issues of Batman or Captain America, whether we knew what they meant or not, it’s a final acceptance of a shift we’ve grown up watching and participating in. In fact, it’s a growing up process in its own right, for the entire comic book industry, and one that feels awfully familiar if you were raised the way I was.

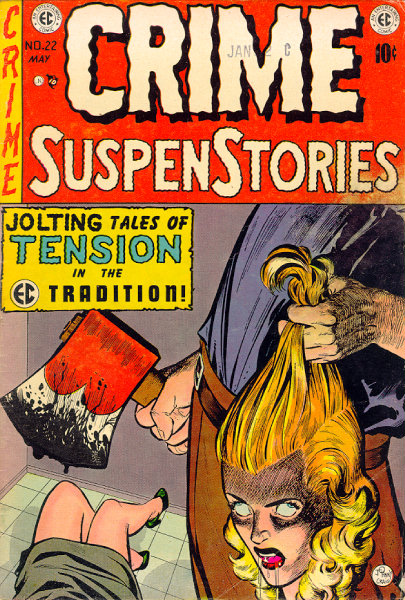

The CCA came about in the 1950s, the so-called ‘Age of Innocence’ – when we needed to be protected from the Commies hiding around every corner, when even married couples on TV slept in two separate beds lest anyone think they actually touched each other after lights out. The booming comic book industry – particularly that rascally William Gaines, creator of Weird Science and MAD Magazine – wasn’t quite playing along at that point; comics actually dared to show violence and sexual innuendo and advertisements for fireworks, and this simply had to be regulated.

Looking at it now, it all reminds me very much of my childhood in an ultra-conservative, strictly Christian household – where my mother judged the books I was bringing home by their cover art, or turned off TV shows in the middle if they were too violent, and where I had to promise that if I bought Weird Al in 3-D I’d tape over the song “Nature Trail to Hell“ because, well, it had Hell right there in the title! I was a wild child about in the way that saying ‘butt’ or taking off Barbie’s clothes is really naughty – and that’s how the CCA feels to me in retrospect, like my parents thinking I couldn’t handle blood or sexuality in even the mildest forms in my fiction. And while that’s somewhat understandable (though not really desirable, and was very frustrating) from parent to child, an industry making those decisions for their public is a lot less acceptable.

But neither the comic book industry, nor the young D.J. Sylvis, took this for too long without finding ways to break the rules. Where I was learning that books with plain covers, particularly from the sci-fi section of the library, might have all sorts of things in them my parents wouldn’t catch on to, underground comics were learning that there were still ways to reach the public even if newsstands wouldn’t carry them without the CAA seal and started showing up in head shops and the like. It may not have been mainstream success, but it didn’t take long for them to catch on, and the grip of the Authority weakened just like my belief that reading about weird alien sex could damn my soul eternally.

The Code itself changed several times as ideas and attitudes expanded, though it was always significantly behind the times and censorious, but after a few decades it lost the greater part of its power. By the time I graduated from high school and stopped worrying so much about what my parents might find out, my local comic book store had everything from books about serial killers to hardcore (drawn) pornography available, and only the books specifically directed at little kids really seemed to worry about the CCA guidelines. Every month or two, even Marvel and DC seemed to be publishing something that pushed the boundaries – stories focusing on drug and alcohol addiction, sex and violence in the revamped House of Mystery, the death of Jason Todd. I spent a lot of time with my nose buried in comics those days, and a lot of fascinating stuff came out of it.

And now, the CCA has officially come to an end, as usual quite a few years after its time. This is where the comparison to maturing into adulthood falls apart a bit – I don’t really know as I’d say society has matured overall from the fifties to now (though than I would really call myself mature, either – I still laugh at the word ‘butt’). I’d say that it’s more difficult these days to mask the true complexity of the world the way authorities used to – when you can find out attitudes and opinions across society with a few keystrokes, it’s harder to convince the greater public that the real enemy is Elvira showing her cleavage on a printed page (for however long printed pages continue to exist).

It’s not really possible to sustain the sort of mindless censorship that the Comics Code Authority stood for, any more than it’s possible for a parent to control what a 39 year-old agnostic liberal essay writer says on a website. Comic books may or may not have grown up – there’s still rampant sexism, excessive violence, cultural insensitivity – but they’ve definitely come to accept that a wider range of complexity should be allowed to exist, that there may be limits to what society finds acceptable but those boundaries were made to be pushed.

That may be an awfully weighty lesson to draw out from a move by Archie Comics, but I think that’s where we are now, and I’m pretty glad to know an art form I love has survived to adulthood. Both mine and theirs.

William Gaines’ Last Laugh by Rev. Syung Myung Me

William Gaines’ Last Laugh by Rev. Syung Myung Me

(Title swiped from Scott Bieser‘s comment on ComicsBeat’s coverage)

I come from a different background than D.J., in that my parents always believed that reading was always a good thing, so they didn’t typically censor my media intake. Mom might make it clear that she did NOT enjoy the antics of Beavis and Butthead, but she knew I was smart enough to not set myself on fire, so there wasn’t really an issue. I just didn’t watch it in front of her — not out of fear or anything, but out of respect for her hatred of the show. There was no secret that I watched it — it just wasn’t her thing, that’s all.

Actually, it was my mom that turned me on to MAD and EC Comics in general, so you can take that as you want. Of course, though, I was a fan of Archie and some of the titles on Marvel’s Star imprint for younger kids, and, so, I’d always see the Comic Code Authority seal. I didn’t really know what that was, nor did I care all that much. As far as I could tell, it was just folks sitting around saying “Hm… pictures? Words? Yep, this is a comic book!” (And, of course, I get the impression that by the 1980s, that’s more or less what they were doing.)

The funny thing is — I’d often censor myself a bit; I didn’t mind “Nature Trail To Hell” so much, but I remember being a little shocked at the line “Tell me tell me tell me/how to make my bustline grow” in In 3-D’s “Midnight Star”. Of course, again, my folks wouldn’t have given a good goddamn, but still — Weird Al’s backing singers mentioned BOOBS. So, I know, I’ve got my own set of weirdnesses, but oddly enough, I’ve never had comics involved with them. Hell, my mom introduced me to the talented pin-up artist Vargas — again, not something you’d expect a mom to share with her son, but good art is good art.

I think that’s how I tend to see the CCA, too — it got in the way of good art. I can see why it was created, but it definitely outlived its usefulness… and may have been that way from the crib, honestly. The funny thing — the idea came from Bill Gaines himself shortly before he was voted out of being able to participate in the actual board itself while his competitors went in for the kill, banning all sorts of silliness like the word “weird”. The CCA, however, prevented a governmental oversight committee or other legislative solutions, so in a way, we have it to thank for keeping comics alive, even if in a crippled state.

Unlike the MPAA, the CCA’s rules and regulations were clear… though often still bafflingly applied. One of the big ones I remember was a reprint of a EC story in one of their short-lived post-Code titles. The story was about an astronaut who landed on a planet to see if they were ready to be invited to a Federation Of Planets sorta thing, but discovered that the inhabitants were split between two different colors (orange and blue, if I recall), and one color treated the other incredibly poorly. The astronaut declares that these aliens were too backward to be accepted — and the pay off is, when the astronaut takes off his helmet, he’s Black. He’s also sweaty, as spacesuits, one would imagine, are pretty warm.

This story was rejected — apparently part of the code was against showing beads of sweat on a Black person. I don’t quite get that, but hey. Gaines raised such a fuss, threatening to go to the media that the CCA censored an anti-racism story for a (nonsensically) racist reason, and the CCA backed down. Still — stories like this are in the minority. Folks like Gaines ended up giving up the fight, ending all his comic lines, and others just ended up bowing to the decisions, no matter how crazy they might be. And, of course, there’s the 1971 anti-dug Spiderman arc that was rejected by the CCA, and simply ran without the seal… and the world didn’t end.

So, what of the CCA? I’m glad it’s finally dead — I’m surprised it lasted this long, but I tend to think it survived more out of a force of habit than anything else. It was only a matter of time before the publishers realized that they didn’t really need this cryptic stamp that no one really knew about anymore. Long gone were the days of comic racks and newsstands displaying big banners telling parents to look for the seal to make sure they were buying their children healthy, safe comics; for decades, it’s just been a little bit of real-estate on the cover that could be better used for other things.