Seijun Suzuki is a master director. You’ve probably seen Branded to Kill in the rotator to the side — and trust me, that’s earned. It’s an outstanding film, and my favorite of all of his (at least of those I’ve seen so far). Suzuki was, for the bulk of his career, a staff director for Nikkatsu, turning out B-movies, genre pictures that were pretty formula.

Or, at least the scripts were… before he got done re-writing them. And this is what ended up being his downfall at Nikkatsu. They weren’t interested in good films or arty films — they wanted cheap money-makers. And too much experimentation gets in the way of that. They wanted disposable — not memorable. In fact, the aforementioned Branded To Kill was the film which led to him getting blacklisted as a film director for a decade, as well as a lawsuit against the film company, which Suzuki won (though it was somewhat of a phyrric victory, as the company was failing by that time and he got only a fraction of what he was looking for).

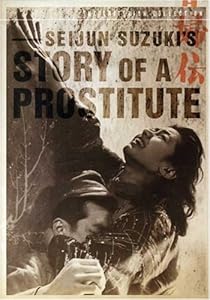

Story of a Prostitute, however, came a few years earlier than Branded To Kill, and, as such, wasn’t quite as Out There as he could be. There are signs, but if anything, the film underscores the saying that in order to be able to properly bend and break the rules, you have to know them backwards and forwards first. Story is one of the clearest examples of Suzuki’s outstanding skills as a filmmaker, even when working on something rather straightforward.

The shots are all picturesque and beautiful; notable scenes include a fantasy sequence where everything is in blinding white, a deep contrast from the utter darkness of the rest of the film, and a scene in which the antagonist, in another fantasy sequence is shown as a photo torn apart, as the lead character fantasizes about his downfall.

This film can be seen as a bookend with his Gate of Flesh from a year earlier (apparently Criterion did, as they released these two at the same time in similar packaging), although this is clearly the superior film. Gate of Flesh was all right, and definitely well-made and exquisitely beautiful, but something about the film didn’t grab me the way Story of a Prostitute does. Both are worth watching, but while I might recommend Gate as a rental, Story would be an excellent purchase.

The story of the film is somewhat of a genre piece, however, it was one of the few that Suzuki enjoyed, having enjoyed the novel it was based on (by Taijito Tamura, who also wrote the novel Gate of Flesh was based on. The film follows a prostitute (oddly enough) in Manchuria who serves with other girls to provide “comfort” to the Japanese soldiers fighting. She is chosen as the special girl by the Lieutenant, although instead she falls in love with his aide. The film is also an indictment on the Japanese sense of honor, part of which is that anyone who is captured by the enemy, regardless of whether or not they speak, is court-martialed and killed. It’s rather subversive in that sense for what’s essentially a B-movie, but, in a way, often those were the most subversive as they typically had the least to lose.

Suzuki’s films often side with the underdog; the eyes and soul of the film belong to Harumi, the prostitute, and it is with her we most sympathize. She lets us see how foolish the war around her is — not on a political level; nothing is ever made as to whether or not the Manchurian War was right or wrong, but on a personal level. And, it’s through her, we see how other people react to her and her position in life. It also happens to be a really intriguing story told perfectly.